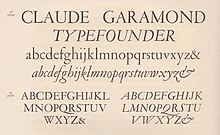

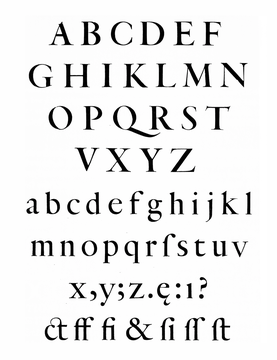

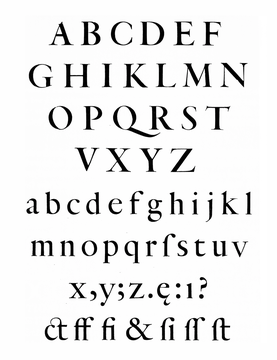

Garamond is a group of many serif typefaces, named for sixteenth-century Parisian engraver Claude Garamond, generally spelled as Garamont in his lifetime. Garamond-style typefaces are popular and particularly often used for book printing and body text.

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Along with blackletter and roman type, it served as one of the major typefaces in the history of Western typography.

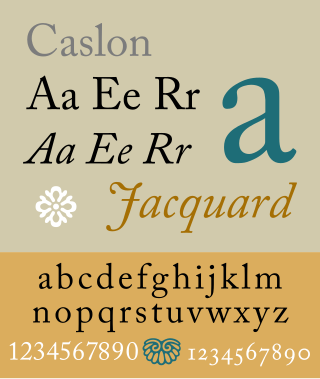

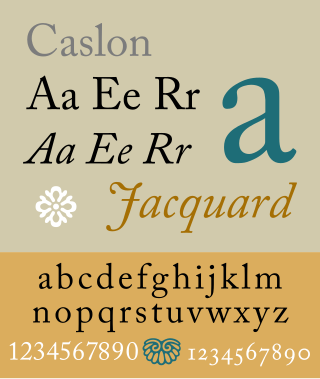

Caslon is the name given to serif typefaces designed by William Caslon I in London, or inspired by his work.

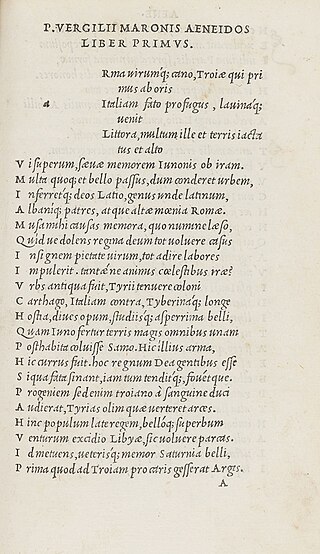

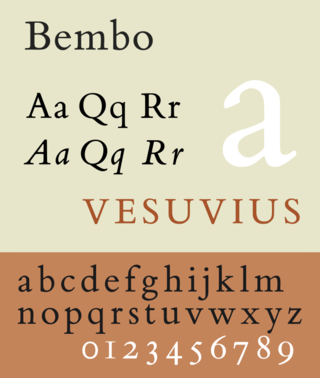

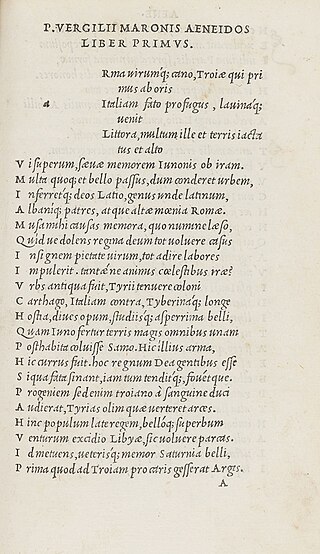

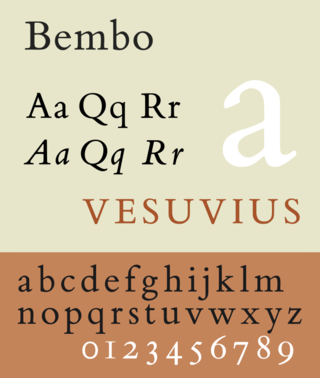

Bembo is a serif typeface created by the British branch of the Monotype Corporation in 1928–1929 and most commonly used for body text. It is a member of the "old-style" of serif fonts, with its regular or roman style based on a design cut around 1495 by Francesco Griffo for Venetian printer Aldus Manutius, sometimes generically called the "Aldine roman". Bembo is named for Manutius's first publication with it, a small 1496 book by the poet and cleric Pietro Bembo. The italic is based on work by Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, a calligrapher who worked as a printer in the 1520s, after the time of Manutius and Griffo.

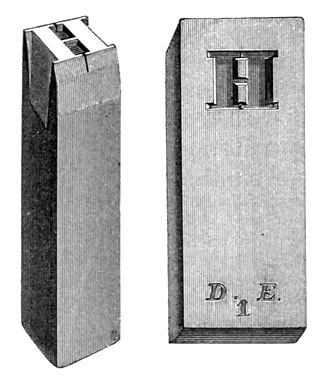

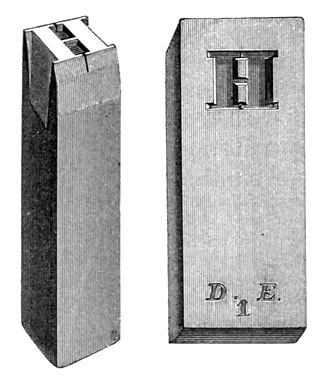

Punchcutting is a craft used in traditional typography to cut letter punches in steel as the first stage of making metal type. Steel punches in the shape of the letter would be used to stamp matrices into copper, which were locked into a mould shape to cast type. Cutting punches and casting type was the first step of traditional typesetting. The cutting of letter punches was a highly skilled craft requiring much patience and practice. Often the designer of the type would not be personally involved in the cutting.

Claude Garamont, known commonly as Claude Garamond, was a French type designer, publisher and punch-cutter based in Paris. Garamond worked as an engraver of punches, the masters used to stamp matrices, the moulds used to cast metal type. He worked in the tradition now called old-style serif design, which produced letters with a relatively organic structure resembling handwriting with a pen but with a slightly more structured and upright design. Considered one of the leading type designers of all time, he is recognised to this day for the elegance of his typefaces. Many old-style serif typefaces are collectively known as Garamond, named after the designer.

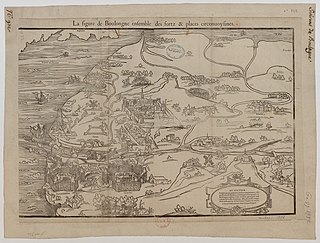

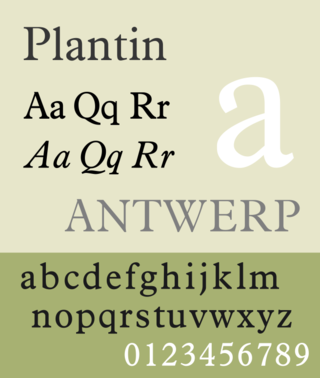

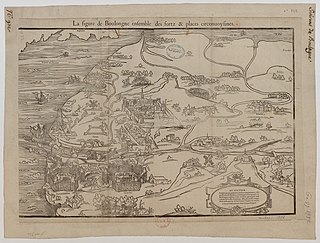

The Plantin–Moretus Museum is a printing museum in Antwerp, Belgium which focuses on the work of the 16th-century printers Christophe Plantin and Jan Moretus. It is located in their former residence and printing establishment, the Plantin Press, at the Vrijdagmarkt in Antwerp, and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2005.

Janson is the name given to a set of old-style serif typefaces from the Dutch Baroque period, and modern revivals from the twentieth century. Janson is a crisp, relatively high-contrast serif design, most popular for body text.

Baskerville is a serif typeface designed in the 1750s by John Baskerville (1706–1775) in Birmingham, England, and cut into metal by punchcutter John Handy. Baskerville is classified as a transitional typeface, intended as a refinement of what are now called old-style typefaces of the period, especially those of his most eminent contemporary, William Caslon.

Beatrice Lamberton Warde was a twentieth-century writer and scholar of typography. As a marketing manager for the British Monotype Corporation, she was influential in the development of printing tastes in Britain and elsewhere in the mid-twentieth century and was recognized at the time as "[o]ne of the few women typographers in the world". Her writing advocated higher standards in printing, and championed intelligent use of historic typefaces from the past, which Monotype specialised in reviving, and the work of contemporary typeface designers.

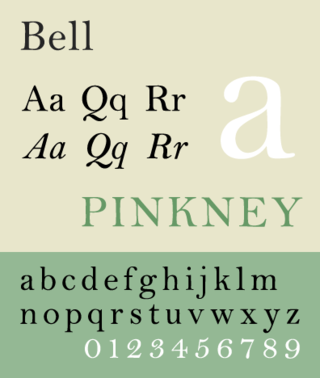

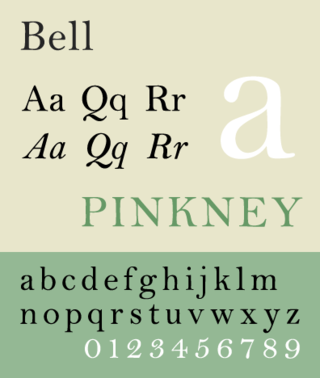

Bell is the name given to a serif typeface designed and cut in 1788 by the punchcutter Richard Austin for the British Letter Foundry, operated by publisher John Bell, and revived several times since.

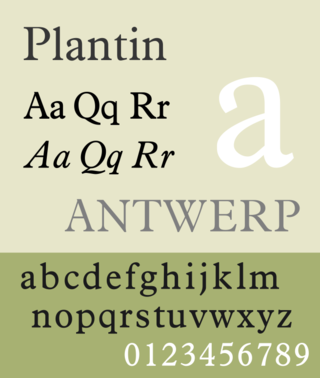

Plantin is an old-style serif typeface. It was created in 1913 by the British Monotype Corporation for their hot metal typesetting system and is named after the sixteenth-century printer Christophe Plantin. It is loosely based on a Gros Cicero roman type cut in the 16th century by Robert Granjon held in the collection of the Plantin–Moretus Museum, Antwerp.

Robert Granjon was a French punchcutter, a designer and creator of metal type, and printer. He worked in Paris, Lyon, Antwerp, and Rome. He is best known for having introduced the typeface style Civilité, for his many italic types and his fleuron designs, although he worked across all genres of typeface and alphabet across his long career.

Les Grecs du roi are a celebrated and influential Greek alphabet typeface in the Greek minuscule style which was cut by the French punchcutter Claude Garamond between 1541 and 1550. Arthur Tilley calls the books printed from them "among the most finished specimens of typography that exist".

Henry Lewis Bullen was an American printer and typographic archivist.

Christoffel van Dijck was a German-born Dutch punchcutter and typefounder, who cut punches and operated a foundry for casting metal type. Van Dijck's type was widely used at a time when Amsterdam had become a major centre of world printing.

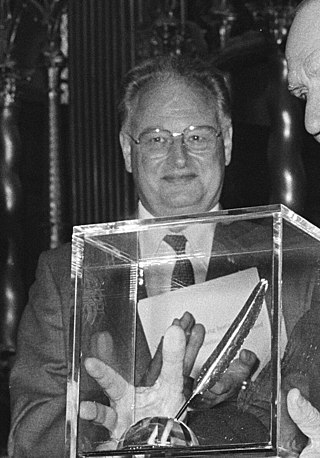

Hendrik Désiré Louis 'Dis' Vervliet was a Belgian librarian and historian of books and printing.

Hendrik van den Keere was a punchcutter, or cutter of punches to make metal type, who lived in Ghent in modern Belgium.

Pierre Haultin was a French printer, publisher, punchcutter and typefounder.

The Caslon type foundry was a type foundry in London which cast and sold metal type. It was founded by the punchcutter and typefounder William Caslon I, probably in 1720. For most of its history it was based at Chiswell Street, Islington, was the oldest type foundry in London, and the most prestigious.