Manzanar is the site of one of ten American concentration camps, where more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II from March 1942 to November 1945. Although it had over 10,000 inmates at its peak, it was one of the smaller internment camps. It is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California's Owens Valley, between the towns of Lone Pine to the south and Independence to the north, approximately 230 miles (370 km) north of Los Angeles. Manzanar means "apple orchard" in Spanish. The Manzanar National Historic Site, which preserves and interprets the legacy of Japanese American incarceration in the United States, was identified by the United States National Park Service as the best-preserved of the ten former camp sites.

During World War II, the United States, by order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, forcibly relocated and incarcerated at least 125,284 people of Japanese descent in 75 identified incarceration sites. Most lived on the Pacific Coast, in concentration camps in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the inmates were United States citizens. These actions were initiated by Executive Order 9066 following Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. Like many Americans at the time, the architects of the removal policy failed to distinguish between Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans. Of the 127,000 Japanese Americans who were living in the continental United States at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, 112,000 resided on the West Coast. About 80,000 were Nisei and Sansei. The rest were Issei immigrants born in Japan who were ineligible for U.S. citizenship under U.S. law.

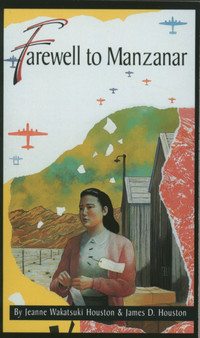

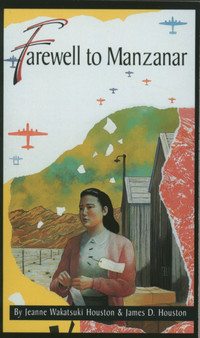

Farewell to Manzanar is a memoir published in 1973 by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston. The book describes the experiences of Jeanne Wakatsuki and her family before, during, and following their relocation to the Manzanar internment camp due to the United States government's internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It was adapted into a made-for-TV movie in 1976 starring Yuki Shimoda, Nobu McCarthy, James Saito, Pat Morita, and Mako.

John Kozo Okada was a Japanese American novelist known for his critically acclaimed novel No-No Boy.

Shikata ga nai, pronounced[ɕi̥kataɡanaꜜi], is a Japanese language phrase meaning "it cannot be helped" or "nothing can be done about it". Shō ga nai (しょうがない), pronounced[ɕoːɡanaꜜi] is an alternative.

The Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) and briefly as the Abraham Relocation Center, was an American concentration camp in which Americans of Japanese descent and immigrants who had come to the United States from Japan, called Nikkei were incarcerated. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, ordering people of Japanese ancestry to be incarcerated in what were euphemistically called "relocation centers" like Topaz during World War II. Most of the people incarcerated at Topaz came from the Tanforan Assembly Center and previously lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. The camp was opened in September 1942 and closed in October 1945.

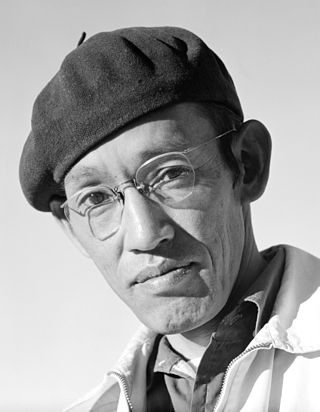

Tōyō Miyatake was a Japanese American photographer, best known for his photographs documenting the Japanese American people and the Japanese American internment at Manzanar during World War II.

Wakako Yamauchi was a Japanese American writer. Her plays are considered pioneering works in Asian-American theater.

Stand Up For Justice: The Ralph Lazo Story (2004) is an educational narrative short film, co-produced by Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress (NCRR) and Visual Communications (VC).

Miné Okubo was an American artist and writer. She is best known for her book Citizen 13660, a collection of 198 drawings and accompanying text chronicling her experiences in Japanese American internment camps during World War II.

James Dudley Houston was an American novelist, poet and editor. He wrote nine novels and a number of non-fiction works.

The Manzanar Children's Village was an orphanage for children of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II as a result of Executive Order 9066, under which President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast of the United States. Contained within the Manzanar concentration camp in Owens Valley, California, it held a total of 101 orphans from June 1942 to September 1945.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was a Japanese American political activist who played a major role in the Japanese American redress movement. She was the lead researcher of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), a bipartisan federal committee appointed by Congress in 1980 to review the causes and effects of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II. As a young woman, Herzig-Yoshinaga was confined in the Manzanar Concentration Camp in California, the Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas, and the Rohwer War Relocation Center, which is also in Arkansas. She later uncovered government documents that debunked the wartime administration's claims of "military necessity" and helped compile the CWRIC's final report, Personal Justice Denied, which led to the issuance of a formal apology and reparations for former camp inmates. She also contributed pivotal evidence and testimony to the Hirabayashi, Korematsu and Yasui coram nobis cases.

Joyce Nakamura Okazaki is an American citizen of Japanese heritage who was forcibly removed with her family from their Los Angeles home and placed in the Manzanar War Relocation camp in 1942. She was photographed by Ansel Adams in both 1943 and 1944 for his book, Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans. In the 2001 reprint of the book, Okazaki's photograph appeared on the book jacket cover. She was the treasurer of the Manzanar Committee, from July 2010 to February 2021, an NGO which promotes education about the World War II incarceration of Japanese-Americans.

Ralph Lazo was the only known non-spouse, non-Japanese American who voluntarily relocated to a Japanese American internment camp during World War II. His experience was the subject of the 2004 narrative short film Stand Up for Justice: The Ralph Lazo Story.

Mary Kageyama Nomura is an American singer of Japanese descent who was relocated and incarcerated for her ancestry at the Manzanar concentration camp during World War II and became known as The songbird of Manzanar.

Yuki Helen Okinaga Hayakawa Llewellyn was an American child survivor of the Japanese internment process during World War II. A 1942 photograph of her sitting on her mother's luggage became an iconic image of the era. In adulthood, Llewellyn was assistant dean of students at the University of Illinois, and frequently spoke on her childhood experience of displacement and incarceration.

Grace Aiko Nakamura was a Japanese American educator and the first Japanese American teacher to be hired in the Pasadena Unified School District.

Wakatsuki Houston, Jeanne. Academic Interview. Nov. 2022