The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associations of the period, it drew largely upon working men and was itself organised on a formal democratic basis.

Thomas Holcroft was an English dramatist, miscellanist, poet and translator. He was sympathetic to the early ideas of the French Revolution and helped Thomas Paine to publish the first part of The Rights of Man.

Thomas Muir, also known as Thomas Muir the Younger of Huntershill, was a Scottish political reformer and lawyer. Muir graduated from Edinburgh University and was admitted to the Faculty of Advocates in 1787, aged 22. Muir was a leader of the Society of the Friends of the People. He was the most important of the group of two Scotsmen and three Englishmen on the Political Martyrs' Monument, Edinburgh. In 1793 they were sentenced to transportation to Botany Bay Australia for sedition.

George Mealmaker was a Scottish radical organiser and writer, born in Dundee, Scotland. Like his father before him he was a weaver by trade.

The Society of the Friends of the People was an organisation in Great Britain that was focused on advocating for parliamentary reform. It was founded by the Whig Party in 1792.

Jeremiah Joyce (1763–1816) was an English Unitarian minister and writer. He achieved notoriety as one of the group of political activists arrested in May 1794.

Thomas Hardy was a British shoemaker who was an early Radical, and the founder, first Secretary, and Treasurer of the London Corresponding Society.

Maurice Margarot (1745–1815) is most notable for being one of the founding members of the London Corresponding Society, a radical society demanding parliamentary reform in the late eighteenth century.

John Thelwall was a radical British orator, writer, political reformer, journalist, poet, elocutionist and speech therapist.

Joseph Gerrald was a political reformer, one of the "Scottish Martyrs". He worked with the London Corresponding Society and the Society for Constitutional Information and also wrote an influential letter, A Convention the Only Means of Saving Us from Ruin. He was arrested for his radical views and convicted of sedition in 1794. Subsequently, he was deported to Sydney, where he died from tuberculosis in 1796.

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall. In a repudiation of the government's policies, they were acquitted by three separate juries in November 1794 to public rejoicing. The treason trials were an extension of the sedition trials of 1792 and 1793 against parliamentary reformers in both England and Scotland.

Thomas Hardy (1757–1804) was a portrait painter born in Derbyshire, England.

The Political Martyrs Monument, located in the Old Calton Burial Ground on Calton Hill, Edinburgh, commemorates five political reformists from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Designed by Thomas Hamilton and erected in 1844, it is a 90 ft (27 m) tall obelisk on a square-plan base plinth, all constructed in ashlar sandstone blocks. As part of the Burial Ground it is Category A listed.

William Skirving was one of the five Scottish Martyrs for Liberty. Active in the cause of universal franchise and other reforms inspired by the French Revolution, they were convicted of sedition in 1793–94, and sentenced to transportation to New South Wales.

The Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1794 was an Act passed by the British Parliament. The Act's long title was An act to empower his Majesty to secure and detain such persons as his Majesty shall suspect are conspiring against his person and government.

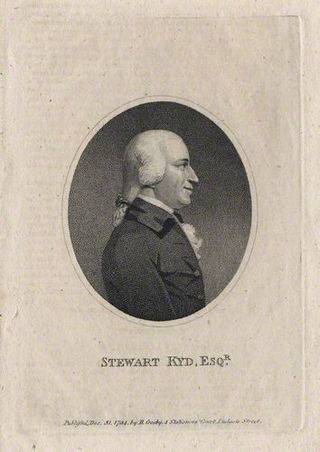

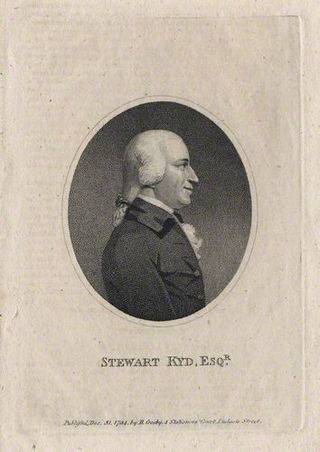

Stewart Kyd was a Scottish politician and legal writer.

Joseph Gurney (1744–1815) was an English shorthand-writer and evangelical activist.

The Popgun Plot was an alleged 1794 conspiracy by three members of the London Corresponding Society to assassinate King George III by means of a poison dart fired from an airgun. Three members, Paul Thomas LeMaitre, John Smith, and George Higgins, were arrested in late 1794, and Robert Thomas Crossfield in December 1795. All four were acquitted of treason in May 1796, on the grounds that the chief witness against them was dead.

Felix Vaughan was an English barrister, known for his role as defence counsel in the treason trials of the 1790s.

Thomas Walker (1749–1817) was an English cotton merchant and political radical.