Related Research Articles

Scottish Church College is a college affiliated by Calcutta University, India. It offers selective co-educational undergraduate and postgraduate studies and is the oldest continuously running Christian liberal arts and sciences college in Asia. It has been rated (A) by the Indian National Assessment and Accreditation Council. Students and alumni call themselves "Caledonians" in the name of the college festival, "Caledonia". The Scottish Church College has been embellished as GRADE-I Heritage Building on 8th November, 2023.

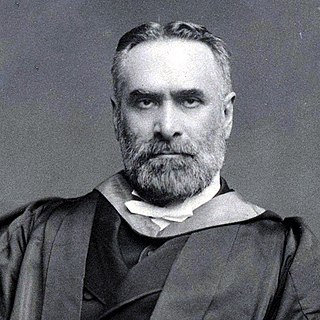

Alexander Duff, was a Scottish missionary in India; where he played a large part in the development of higher education. He was a Moderator of the General Assembly and convener of the foreign missions committee of the Free Church of Scotland and a scientific liberal reformer of anglicized evangelism across the Empire. He was the first overseas missionary of the Church of Scotland to India. On 13 July 1830 he founded the General Assembly's Institution in Calcutta, now known as the Scottish Church College. He also played a part in establishing the University of Calcutta. He was twice Moderator of the Free Church of Scotland in 1851 and 1873, the only person to serve the role twice.

Reverend Lal Behari Day was an Indian writer and journalist, who converted to Christianity, and became a Christian missionary himself.

The Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, also known as the Church of England Zenana Mission, was a British Anglican missionary society established to spread Christianity in India. It would later expand its Christian missionary work into Japan and Qing Dynasty China. In 1957 it was absorbed into the Church Missionary Society (CMS).

Protestants in India are a minority and a sub-section of Christians in India and also to a certain extent the Christians in Pakistan before the Partition of India, that adhere to some or all of the doctrines of Protestantism. Protestants in India are a small minority in a predominantly Hindu majority country, but form majorities in the north-eastern states of Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland. They are also significant minorities in Punjab region, Konkan region, Bengal, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, with various communities in east coast and northern states. Protestants can trace their origins back to the Protestant Revolution of the 16th century. There are an estimated 20 million Protestants and 16 million Pentecostals in India.

Hana Catherine Mullens (1826–1861) was a European Christian missionary, educator, translator and writer. She was a leader of zenana missions, setting up schools for girls and writing what is arguably the first novel in Bengali. She spent most of her life in Calcutta, then the capital of British India, and was fluent in the Bengali language.

The International Service Fellowship, more commonly known as Interserve, is an interdenominational Protestant Christian charity which was founded in London in 1852. For many years it was known as the Zenana Bible and Medical Missionary Society and it was run entirely by women.

John Anderson (1805–1855) was a Scottish missionary and the founder of the mission of the Free Church of Scotland at Madras, India.

Scottish-Indians are Indian citizens of mixed Indian and Scots ancestry or people of Scottish descent born or living in India. Like Irish Indians, a Scottish-Indian can be categorized as an Anglo-Indian. Scottish Indians celebrate Scottish culture, with traditional Scottish celebrations like Burns Night widely observed among the community.

Robert Clark (1825–1900), and his colleague Thomas Henry Fitzpatrick, were the first English Church Mission Society (CMS) missionaries in the Punjab. Clark was the first missionary to the Afghans, and was the first agent of the Church to enter the city of Leh.

John Anderson Graham was a Scottish minister and the first missionary from Young Men's Guild sent to North Eastern Himalayan region Kalimpong—then in British Sikkim, currently in West Bengal.

Rev. John Breeden was an English Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society missionary in the Madras Presidency. He was an educationalist and the founder of St George's Homes, an orphanage-cum-school for abandoned and deprived children of Eurasians or Anglo-Indians in Kodaikanal, later renamed as The Laidlaw Memorial School, Ketti in the Nilgiris.

William Hastie MA DD was a Scottish clergyman and theologian. He produced the first English translation of the Universal Natural History and Theory of Heaven, by Immanuel Kant. Hastie led the General Assembly's Institution in Calcutta, where he was credited with developing the Hindu advocate Swami Vivekananda. Hastie recovered from a ruinous libel case in Calcutta to become the Professor of Divinity at University of Glasgow.

The zenana missions were outreach programmes established in British India with the aim of converting women to Christianity. From the mid 19th century, they sent female missionaries into the homes of Indian women, including the private areas of houses - known as zenana - that male visitors were not allowed to see. Gradually these missions expanded from purely evangelical work to providing medical and education services. Hospitals and schools established by these missions are still active, making the zenana missions an important part of the history of Christianity in India.

Woman's Union Missionary Society of America for Heathen Lands was an American Christian mission organization. Established in 1861, its headquarters were at 41 Bible House, Astor Place, New York City. The first meeting called to consider organizing a society was gathered in a private parlor in New York City on January 9, 1861, and addressed by a returned missionary from Burma. At a subsequent meeting on January 10, the organization was effected, with Sarah Platt Doremus as president. The society's object was to "send out and maintain single women as Bible-readers and teachers, and to raise up native female laborers in heathen lands".

The Church Missionary Society in India was a branch organisation established by the Church Missionary Society (CMS), which was founded in Britain in 1799 under the name the Society for Missions to Africa and the East, as a mission society working with the Anglican Communion, other Protestants, and Orthodox Christians around the world. In 1812, the British organization was renamed the Church Missionary Society.

John Murray Mitchell was a Scottish missionary and orientalist who worked in his country of birth, India and France.

Thomas Smith was a Scottish missionary and mathematician who was instrumental in establishing India's zenana missions in 1854. He served as Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland 1891/92.

Kali Charan Chatterjee D. D. (1839–1916), also spelt as Kali Charan Chatterji or K.C. Chatterjea, was a Bengali Christian missionary who worked with the American Presbyterian Mission in Hoshiarpur, Punjab and served as the first moderator of the Presbyterian Church in India upon its formation in 1904.

References

- ↑ Pamela Kanwar, Imperial Simla: The Political Culture of the Raj (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 176.

- ↑ Forgue Parish Register; William Ewing, Annals of the Free Church of Scotland.

- ↑ Ewing's Annals.

- ↑ 1841 Census; Kelso Chronicle, 20 March 1846; Glasgow Saturday Post, 8 October 1864.

- ↑ North and South Shields Gazette, 2 July 1852.

- ↑ Aberdeen Press and Journal, 11 August 1852.

- ↑ George Smith, Life of Alexander Duff, DD, LLD (A. C. Armstrong, New York, 1879), Vol. II, pp. 271, 360.

- ↑ Calcutta Review, No. L, Vol. XXV (1855), p. 88, and Miscellaneous Notices xxx-xxxiv.

- ↑ Alexander Duff, Female Education in India, being the substance of An Address Delivered at the First Assembly of the Scottish Ladies’ Association in Connection with the Church of Scotland for the Promotion of Female Education in India (John Johnstone, Edinburgh, 1839).

- ↑ Rev. E. Storrow, Our Indian Sisters (The Religious Tract Society, 1899), pp. 209-215 ; George Smith, Life of Alexander Duff, p. 360, and Twelve Pioneer Missionaries (Thomas Nelson & Sons, London, 1900), p. 80; Julius Richter, DD, A History of Missions in India, trans. Sydney H Moore (Fleming H. Revell Company, New York, 1908); Arthur T. Pierson, DD, The New Acts of the Apostles (James Nisbet, London, 1901), p. 134 ; Benoy Bhusan Roy and Pranati Ray, Zenana Mission: The Role of Christian Missionaries for the Education of Women in 19th Century Bengal (ISPCK, Delhi, 1998), pp. 19, 133-136.

- ↑ Calcutta Review, No. L, Vol. XXV (1855), p. 88, and Miscellaneous Notices xxx-xxxiv.

- ↑ Rev. E. Storrow, Our Indian Sisters (The Religious Tract Society, 1899), pp. 209-215.

- ↑ Mary Weitbrecht, The Women of India and Christian Work in the Zenana (James Nisbet & Co., 1875), p. 71.

- ↑ Smith, Life of Alexander Duff, p. 361; Rev. John Fordyce, "After Many Days", July 1866, printed in Women’s Work in Heathen Lands (J. & R. Parlane, Paisley) and quoted by Smith in Twelve Pioneer Missionaries, pp. 80-83 ; Calcutta Review, ut supra.

- ↑ Weitbrecht, ut supra; she adds, “All honour to the Christian love and zeal, the really chivalrous attempt of our beloved brother Rev. John Fordyce”.

- ↑ Richter, p. 339.

- ↑ Dundee Courier & Argus, 23 September 1876; Statistical Tables of Protestant Missionaries in India for 1890, cited in Richard Lovett, History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895 (London: Henry Frowde, 1899), Vol. 2, p. 241.

- ↑ Berwickshire News and General Advertiser, 1 October 1889.

- ↑ Illustrated Berwick Journal, 21 September 1866.

- ↑ The Scotsman, 10 March 1870; Cardiff Times, 29 January 1870; Smith, Life of Alexander Duff, Vol. II, p. 441.

- ↑ Glasgow Herald, 12 February 1885.

- ↑ Ewing's Annals.

- ↑ 25th Annual Report of the Anglo-Indian Evangelisation Society (1895), p. 7.

- ↑ Cambridge Daily News, 24 November 1902.

- ↑ Richter, p. 339.

- ↑ Dundee Courier & Argus, 23 September 1876.

- ↑ J. C. Pollock, Shadows Fall Apart: The Story of the Zenana Bible and Medical Mission (Hodder & Stoughton, 1958), pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Pamela Kanwar, Imperial Simla: The Political Culture of the Raj (Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 176.

- ↑ Mulk Raj Anand, Coolie (Penguin Books India, 1993), pp. 261-2.

- ↑ Free Church Ladies’ Society Minute Book, 12 March 1853.

- ↑ Dumfries & Galloway Standard, 15 September 1852.

- ↑ Richter, p. 338, and Fordyce, ut supra.