The American Revolution was a rebellion and political movement in the Thirteen Colonies which peaked when colonists initiated an ultimately successful war for independence against the Kingdom of Great Britain. Leaders of the American Revolution were colonial separatist leaders who originally sought more autonomy as British subjects, but later assembled to support the Revolutionary War, which ended British colonial rule over the colonies, establishing their independence as the United States of America in July 1776.

John Hancock was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He was the longest-serving president of the Continental Congress, having served as the second president of the Second Continental Congress and the seventh president of the Congress of the Confederation. He was the first and third governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He is remembered for his large and stylish signature on the United States Declaration of Independence, so much so that in the United States, John Hancock or Hancock has become a colloquialism for a person's signature. He also signed the Articles of Confederation, and used his influence to ensure that Massachusetts ratified the United States Constitution in 1788.

The Boston Massacre was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which nine British soldiers shot several of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing them verbally and throwing various projectiles. The event was heavily publicized as "a massacre" by leading Patriots such as Paul Revere and Samuel Adams. British troops had been stationed in the Province of Massachusetts Bay since 1768 in order to support crown-appointed officials and to enforce unpopular Parliamentary legislation.

Thomas Hutchinson was an American merchant, politician, historian, and colonial administrator who repeatedly served as governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in the years leading up to the American Revolution. He has been described as "the most important figure on the loyalist side in pre-Revolutionary Massachusetts". Hutchinson was a successful merchant and politician who was active at high levels of the Massachusetts colonial government for many years, serving as lieutenant governor and then governor from 1758 to 1774. He was a politically polarizing figure who came to be identified by John Adams and Samuel Adams as a supporter of unpopular British taxes, despite his initial opposition to Parliamentary tax laws directed at the colonies. Hutchinson was blamed by British Prime Minister Lord North for being a significant contributor to the tensions that led to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War.

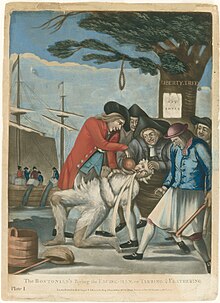

Tarring and feathering is a form of public torture where a victim is stripped naked, or stripped to the waist, while wood tar is either poured or painted onto the person. The victim then either has feathers thrown on them or is rolled around on a pile of feathers so that they stick to the tar.

William Molineux was a hardware merchant in colonial Boston of Irish descent best known for his role in the Boston Tea Party of 1773 and earlier political protests.

A writ of assistance is a written order issued by a court instructing a law enforcement official, such as a sheriff or a tax collector, to perform a certain task. Historically, several types of writs have been called "writs of assistance". Most often, a writ of assistance is "used to enforce an order for the possession of lands". When used to evict someone from real property, such a writ is also called a writ of restitution or a writ of possession. In the area of customs, writs of assistance date from Colonial times. They were issued by the Court of Exchequer to help customs officials search for smuggled goods. These writs were called "writs of assistance" because they called upon sheriffs, other officials, and loyal subjects to "assist" the customs official in carrying out his duties.

The Sons of Liberty was a loosely organized, clandestine, sometimes violent, political organization active in the Thirteen American Colonies founded to advance the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. It played a major role in most colonies in battling the Stamp Act in 1765 and throughout the entire period of the American Revolution. Historian David C. Rapoport called the activities of the Sons of Liberty "mob terror."

Patriots, also known as Revolutionaries, Continentals, Rebels, or Whigs, were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who opposed the Kingdom of Great Britain's control and governance during the colonial era, and supported and helped launch the American Revolution that ultimately established American independence. Patriot politicians led colonial opposition to British policies regarding the American colonies, eventually building support for the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which was adopted unanimously by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. After the American Revolutionary War began the year before, in 1775, many patriots assimilated into the Continental Army, which was commanded by George Washington and which secured victory against the British Army, leading the British to acknowledge the sovereign independence of the colonies, reflected in the Treaty of Paris, which led to the establishment of the United States in 1783.

George Robert Twelves Hewes was a participant in the political protests in Boston at the onset of the American Revolution, and one of the last survivors of the Boston Tea Party and the Boston Massacre. Later he fought in the American Revolutionary War as a militiaman and privateer. Shortly before his death at the age of 98, Hewes was the subject of two biographies and much public commemoration.

The MassachusettsPowder Alarm was a major popular reaction to the removal of gunpowder from a magazine near Boston by British soldiers under orders from General Thomas Gage, royal governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, on September 1, 1774. In response to this action, amid rumors that blood had been shed, alarm spread through the countryside to Connecticut and beyond, and American Patriots sprang into action, fearing that war was at hand. Thousands of militiamen began streaming toward Boston and Cambridge, and mob action forced Loyalists and some government officials to flee to the protection of the British Army. A similar event, also called The Powder Alarm, occurred in Virginia in April, 1775.

The Liberty Tree (1646–1775) was a famous elm tree that stood in Boston, Massachusetts near Boston Common in the years before the American Revolution. In 1765, Patriots in Boston staged the first act of defiance against the British government at the tree. The tree became a rallying point for the growing resistance to the rule of Britain over the American colonies, and the ground surrounding it became known as Liberty Hall. The Liberty Tree was felled in August 1775 by Loyalists led by Nathaniel Coffin Jr. or by Job Williams.

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, by the Sons of Liberty in Boston in colonial Massachusetts. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the East India Company to sell tea from China in American colonies without paying taxes apart from those imposed by the Townshend Acts. The Sons of Liberty strongly opposed the taxes in the Townshend Act as a violation of their rights. In response, the Sons of Liberty, some disguised as Native Americans, destroyed an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company.

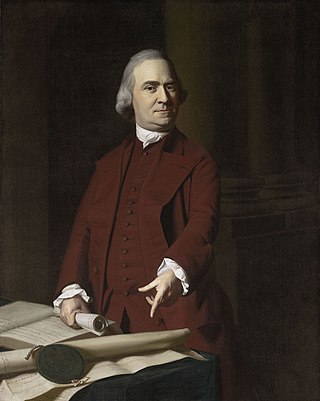

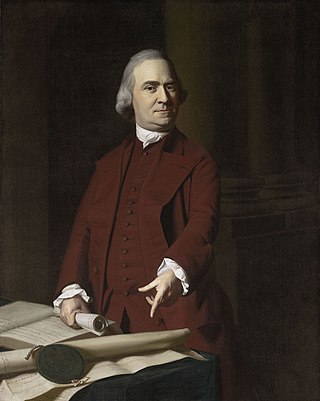

Samuel Adams was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, a signer of the Declaration of Independence and other founding documents, and one of the architects of the principles of American republicanism that shaped the political culture of the United States. He was a second cousin to his fellow Founding Father, President John Adams.

The Philadelphia Tea Party was an incident in late December 1773, shortly after the more famous Boston Tea Party, in which a British tea ship was intercepted by American colonists and forced to return its cargo to Great Britain.

During the American Revolution, those who continued to support King George III of Great Britain came to be known as Loyalists. Loyalists are to be contrasted with Patriots, who supported American republicanism. Historians have estimated that during the American Revolution, between 15 and 20 percent of the white population of the colonies, or about 500000 people, were Loyalists. As the war concluded with Great Britain defeated by the Americans and the French, the most active Loyalists were no longer welcome in the United States, and sought to move elsewhere in the British Empire. The large majority of the Loyalists remained in the United States, however, and enjoyed full citizenship there.

Captain Daniel Malcolm was an American merchant, sea captain, and smuggler. Malcolm was known for resisting the British authorities in the years leading up to the American Revolutionary War. He was the brother of John Malcolm, a minor British customs officer who was violently tarred and feathered by a Boston mob.

The Loyal Nine were nine American patriots from Boston who met in secret to plan protests against the Stamp Act of 1765. Mostly middle-class businessmen, the Loyal Nine enlisted Ebenezer Mackintosh to rally large crowds of commoners to their cause and provided the protesters with food, drink, and supplies. A precursor to the Sons of Liberty, the group is credited with establishing the Liberty Tree as a central gathering place for Boston patriots.

The Worcester Revolt, or Worcester Revolution of 1774, was a confrontation between American militiamen and the British colonial authorities in Worcester, Massachusetts on September 6, 1774, during the American Revolution.