John W. Lindsey | |

|---|---|

"100 Negroes for Sale" The Weekly Advertiser, June 8, 1853 | |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

John W. Lindsey was a slave trader based in Montgomery, Alabama, United States in the 1840s and 1850s.

John W. Lindsey | |

|---|---|

"100 Negroes for Sale" The Weekly Advertiser, June 8, 1853 | |

| Occupation | Slave trader |

John W. Lindsey was a slave trader based in Montgomery, Alabama, United States in the 1840s and 1850s.

Frederic Bancroft described the nature of the Montgomery slave market in his 1931 history Slave-Trading in the Old South :

Montgomery, the capital of Alabama and a good shipping-point, attracted politicians, planters and much general business, although in 1860 its total population was less than 9,000, of whom more than half were slaves and 102 were free colored. Its slave-trade was patronized chiefly by the central part of the State, for northern Alabama drew supplies from markets in other States, and Montgomery traders had competitors in Columbus, Georgia, on the east, Selma on the west, and Mobile on the southwest. Yet the capital did a thriving trade in slaves. The City Directory for 1859 listed four 'slave depots' along with the same number of banking establishments, whereas for the joyful visitors to the first capital of the Confederacy in February, 1861, there were only four regular hotels. [1]

According to the 1950 history Slavery in Alabama, the records of the Montgomery County probate court clearly reveal the names of the major slave traders working in the city, as they would return year after year to harvest unwanted slaves from the estates of the dead and carry them off to be resold. [2] The names of traders and trading firms that recurred most frequently in records dating from 1838 to 1860 were Hill & Hartwell, Williamson & Puryear, Brown & Watson, Mason Harwell, and Lindsey. [2]

A runaway slave ad placed by H. M. Waters of Coffee County, Alabama in 1851 sought the return, for a reward of $30, of his slaves Joe and Adeline, about whom he wrote, "Joe is about 6 feet 8 inches high, and about 35 years of age, rather a bright colored negro, and has had the small pox. Adeline is of medium size, black, and has a downcast look when spoken to, and is about 32 years of age. I purchased the above negroes from Lindsey, a negro trader in Montgomery. They may possibly be making for that place or Prairie Bluff on the Alabama river." [3]

Lindsey advertised his business in the newspaper throughout 1852 and 1853, and one of the "100 Negroes for Sale" ads caught the attention of Harriet Beecher Stowe, who included it in her non-fiction polemic, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin . She reprinted it, with the commentary, "Mr. Lindsey is going to be receiving, from time to time, all the season, and will sell as cheap as anybody; so there's no fear of the supply falling off...Query: Are these Messrs. Sanders & Foster, and J. W. Lindsey, and S. N. Brown, and McLean, and Woodroof, and McLendon, all members of the church, in good and regular standing? Does the question shock you? Why so? Why should they not be? The Rev. Dr. Smylie, of Mississippi, in a document endorsed by two Presbyteries, says distinctly that the Bible gives a right to buy and sell slaves." [4]

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), which depicts the harsh conditions experienced by enslaved African Americans. The book reached an audience of millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and in Great Britain, energizing anti-slavery forces in the American North, while provoking widespread anger in the South. Stowe wrote 30 books, including novels, three travel memoirs, and collections of articles and letters. She was influential both for her writings as well as for her public stances and debates on social issues of the day.

The Pearl incident was the largest recorded nonviolent escape attempt by enslaved people in United States history. On April 15, 1848, seventy-seven slaves attempted to escape Washington D.C. by sailing away on a schooner called The Pearl. Their plan was to sail south on the Potomac River, then north up the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River to the free state of New Jersey, a distance of nearly 225 miles (362 km). The attempt was organized by both abolitionist whites and free blacks, who expanded the plan to include many more enslaved people. Paul Jennings, a former slave who had served President James Madison, helped plan the escape.

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson, "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the 77 slaves who tried to escape from Washington, D.C. on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

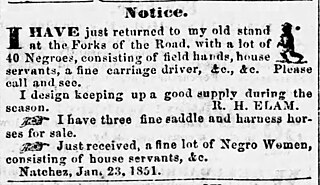

The Forks of the Road was a slave market in Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. The Forks of the Road market was located about a mile from downtown Natchez at the intersection of Liberty Road and Washington Road, which has since been renamed to D'Evereux Drive in one direction and St. Catherine Street in the other. The market differed from many other slave sellers of the day by offering individuals on a first-come first-serve basis rather than selling them at auction, either singly or in lots. At one time the Forks of the Road was the second-largest slave market in the United States, trailing only New Orleans.

The history of slavery in Tennessee began when it was the old Southwest Territory and thus the law regulating slavery in Tennessee was broadly derived from North Carolina law, and was initially comparatively "liberal." However, after statehood, as the fear of slave rebellion and the threat to slavery posed by abolitionism increased, the laws became increasingly punitive: after 1831, "punishments were increased and privileges and immunities were lessened and circumvented." Tennessee was one of five states that allowed slaves the right of a jury trial, and one of three states that never passed anti-literacy laws, although the punishment for forging a slave pass was up to 39 lashes.

Byrd Hill was a slave trader of Tennessee and Mississippi prior to the American Civil War. Byrd Hill has been described as one of the "big four" slave traders in the centrally located city of Memphis on the Mississippi River. Hill was partners for a time with Nathan Bedford Forrest and is believed to have resold six of the Africans illegally trafficked to the United States on the Wanderer in 1859. Hill also made a fleeting appearance in Harriet Beecher Stowe's A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin.

This is a bibliography of works regarding the internal or domestic slave trade in the United States.

Capt. Montgomery Little, CSA was an American slave trader and a Confederate Army cavalry officer who served in Nathan Bedford Forrest's Escort Company. Little was killed in action during the American Civil War at the Battle of Thompson's Station.

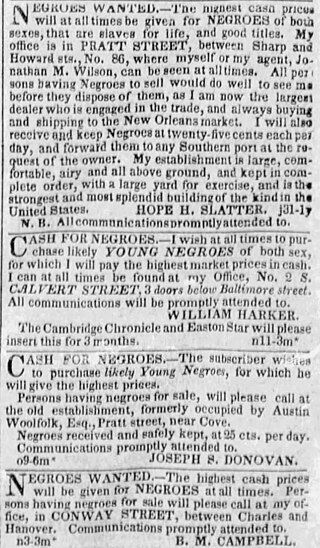

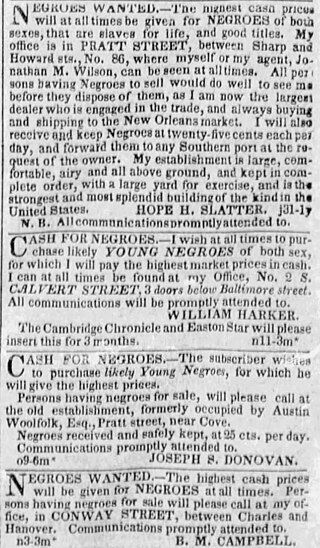

Bernard Moore Campbell and Walter L. Campbell operated an extensive slave-trading business in the antebellum U.S. South. B. M. Campbell, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Joseph S. Donovan, and Hope H. Slatter, has been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9,000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans." Bernard and Walter were brothers.

Mason Harwell was an auctioneer, insurance broker, and a leading, if not the leading, slave trader in antebellum Montgomery, Alabama. According to Slavery in Alabama (1950), "After 1840 Montgomery was the principal market in the state." Sales in 1850s Montgomery often took place outdoors at a central landmark called the Artesian Basin. Around the turn of the century, an older resident of Montgomery told historian Frederic Bancroft, author of Slave-Trading in the Old South, that Harwell was "a man of respectable standing." Mason Harwell worked out of 21 Market Street. He had a second location at Coosa St. and Monroe.

Fugitive slave advertisements in the United States, or runaway slave ads, were paid classified advertisements describing a missing person and usually offering a monetary reward for the recovery of the valuable chattel. Fugitive slave ads were a unique vernacular genre of non-fiction specific to the antebellum United States. These ads often include detailed biographical information about individual enslaved Americans including "physical and distinctive features, literacy level, specialized skills," and "if they might have been headed for another plantation where they had family, or if they took their children with them when they ran."

Slave markets and slave jails in the United States were places used for the slave trade in the United States from the founding in 1776 until the total abolition of slavery in 1865. Slave pens, also known as slave jails, were used to temporarily hold enslaved people until they were sold, or to hold fugitive slaves, and sometimes even to "board" slaves while traveling. Slave markets were any place where sellers and buyers gathered to make deals. Some of these buildings had dedicated slave jails, others were negro marts to showcase the slaves offered for sale, and still others were general auction or market houses where a wide variety of business was conducted, of which "negro trading" was just one part.

Theophilus Freeman was a 19th-century American slave trader of Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi. He was known in his own time as wealthy and problematic. Freeman's business practices were described in two antebellum American slave narratives—that of John Brown and that of Solomon Northup—and he appears as a character in both filmed dramatizations of Northrup's Twelve Years a Slave.

Joseph S. Donovan was an American slave trader known for his slave jails in Baltimore, Maryland. Donovan was a major participant in the interregional slave trade, building shipments of enslaved people from the Upper South and delivering them to the Deep South where they would be used, for the most part, on cotton and sugar plantations. As one Baltimore historical researcher and tour guide summarized, "the change from raising tobacco to wheat in the region caused a surplus of labor, whereas the South needed more labor due to the invention of the cotton gin". Donovan, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Bernard M. Campbell, and Hope H. Slatter, have been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans."

Seth Woodroof was a slave trader based in Lynchburg in central Virginia, United States. He was an interstate trader who ran what the Lynchburg Museum called the "most active and infamous" slave pen in the city. He is believed to have been actively trading from approximately 1830 until the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Woodroof sat on the Lynchburg city council from 1858 to 1865.

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Family separation in American slavery was extremely common. According to one historian of the slave trade in the United States, "The magnitude of the trade, in terms of the lives it affected and families it destroyed, is without a doubt greater than any Civil War battlefield." One survivor of American slavery told the WPA Slave Narratives project, "If you want to know what unhappiness means, just stand on the slave block and hear the auctioneer's voice selling you away from the folks you love." There is widespread evidence of the pervasive nature of family separation: "A central feature of virtually every slave autobiography and of many of the slave interviews, for example, is the trauma caused slaves by forced family separation."

William Harker was a 19th-century American slave trader notable for his longevity. As historian Frederic Bancroft put it in Slave Trading in the Old South (1931): "There seems to have been less slave-trading in Maryland during the 'fifties than during the 'thirties but somewhat more than during the 'forties. The scouring of all agricultural counties continued. The pride of possessing slaves was lessening and the profit of selling them was increasing. With each year new traders came and some of the old were lost sight of. William Harker was a remarkable exception, for he was 'in the market' for a quarter of a century—1835–59, and he bought 'all likely negroes from 8 to 40 years of age'."