The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any significant fighting as King Louis died of dysentery shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia. The Treaty of Tunis was negotiated between the Crusaders and the Hafsids. No changes in territory occurred, though there were commercial and some political rights granted to the Christians. The Crusaders withdrew back to Europe soon after.

The Tarasque is a creature from French mythology. According to the Golden Legend, the beast had a lion-like head, a body protected by turtle-like carapace(s), six feet with bear-like claws, a serpent's tail, and could expel a poisonous breath.

Bohemond VI, also known as the Fair, was the prince of Antioch and count of Tripoli from 1251 until his death. He ruled while Antioch was caught between the warring Mongol Empire and Mamluk Sultanate. He allied with the Mongols against the Muslim Mamluks and his Crusaders fought alongside the Mongols in their battles against the Mamluks. The Mamluks would achieve a historic victory against the Mongols and halt their advance westwards at the Battle of Ain Jalut. In 1268 Antioch was captured by the Mamluks under Baybars, and he was thenceforth a prince in exile. He was succeeded by his son, Bohemond VII.

Brunetto Latini was an Italian philosopher, scholar, notary, politician and statesman.

The Chanson d'Antioche is a chanson de geste in 9000 lines of Alexandrin in stanzas called laisses, now known in a version composed about 1180 for a courtly French audience and embedded in a quasi-historical cycle of epic poems inspired by the events of 1097–99, the climax of the First Crusade: the conquest of Antioch and of Jerusalem and the origins of the Crusader states. The Chanson was later reworked and incorporated in an extended Crusade cycle, of the 14th century, which was far more fabulous and embroidered, more distinctly romance than epic.

Philip Ι of Montfort was Lord of La Ferté-Alais and Castres-en-Albigeois 1228–1270, Lord of Tyre 1246–1270, and Lord of Toron aft. 1240–1270. He was the son of Guy of Montfort and Helvis of Ibelin.

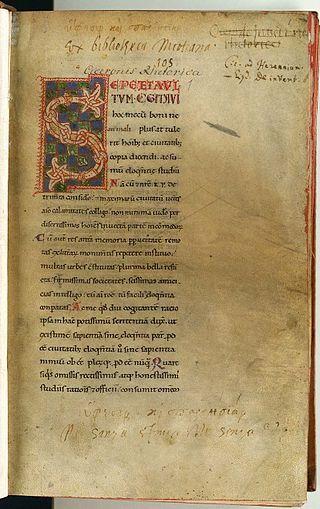

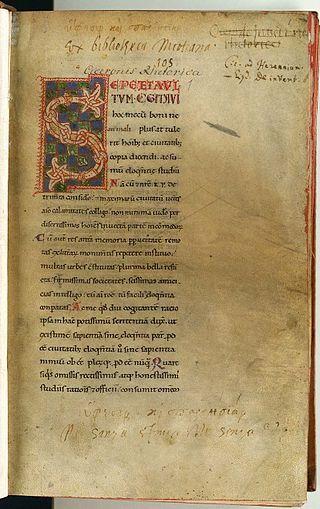

De Inventione is a handbook for orators that Cicero composed when he was still a young man. Quintilian tells us that Cicero considered the work rendered obsolete by his later writings. Originally four books in all, only two have survived into modern times. It is also credited with the first recorded use of the term "liberal arts" or artes liberales, though whether Cicero coined the term is unclear. The text also defines the concept of dignitas: dignitas est alicuius honesta et cultu et honore et verecundia digna auctoritas.

Michael the Syrian ,(Classical Syriac: ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܣܽܘܪܝܳܝܳܐ, romanized: Mīkhoʾēl Sūryoyo), died 1199 AD, also known as Michael the Great or Michael Syrus or Michael the Elder, to distinguish him from his nephew, was a patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 1166 to 1199. He is best known today as the author of the largest medieval Chronicle, which he wrote in the Syriac language. Some other works and fragments written by him have also survived.

Burchard of Mount Sion, was a German priest, Dominican friar, pilgrim and author probably from Magdeburg in northern Germany, who travelled to the Middle East at the end of the 13th century. There he wrote his book called: Descriptio Terrae Sanctae or "Description of the Holy Land" which is considered to be of "extraordinary importance".

Maria of Antioch-Armenia (1215–1257) was lady of Toron from 1229 to her death. She was the elder daughter of Raymond-Roupen, prince of Antioch, and of Helvis of Lusignan. She derived her title of Lady of Toron and claim to the throne of Armenia from her father.

Aimery or Aymery of Limoges, also Aimericus in Latin, Aimerikos in Greek and Hemri in Armenian, was a Roman Catholic ecclesiarch in Frankish Outremer and the fourth Latin Patriarch of Antioch from c. 1140 until his death. Throughout his lengthy episcopate he was the most powerful figure in the Principality of Antioch after the princes, and often entered into conflict with them. He was also one of the most notable intellectuals to rise in the Latin East.

Various species of mythical headless men were rumoured, in antiquity and later, to inhabit remote parts of the world. They are variously known as akephaloi or Blemmyes and described as lacking a head, with their facial features on their chest. These were at first described as inhabitants of ancient Libya or the Nile system (Aethiopia). Later traditions confined their habitat to a particular island in the Brisone River, or shifted it to India.

Otia Imperialia is an early 13th-century encyclopedic work, the best known work of Gervase of Tilbury. It is an example of speculum literature. Also known as the "Book of Marvels", it primarily concerns the three fields of history, geography, and physics, but its credibility has been questioned by numerous scholars including philosopher Gottfried Leibniz, who was alerted to the fact that it contains many mythical stories. Its manner of writing is perhaps because the work was written to provide entertainment to Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV. However, many scholars consider it a very important work in that it "recognizes the correctness of the papal claims in the conflict between Church and Empire." It was written between 1210 and 1214, although some give the dates as between 1209 and 1214 and numerous authors state it was published c.1211. These earlier dates must be questioned, however, as the Otia contains stories that take place in 1211 and later. S. E. Banks and James W. Binns, editors and translators of what is considered to be the definitive version of the Otia, suggest that the work was completed in the last years of Otto IV's life, saying "it seems most likely [...] that the work was sent to Otto sometime in 1215", due to the inclusion of the death of William the Lion, King of Scotland, which took place in 1214, and the fact that King John was still living while it was written; John died in 1216.

Mireille Issa is a Lebanese medievalist born in Beirut. She studies the Late Latin period of Antiquity.

Qenneshre was a large West Syriac monastery between the 6th and 13th centuries. It was a centre for the study of ancient Greek literature and the Greek Fathers, and through its Syriac translations it transmitted Greek works to the Islamic world. It was "the most important intellectual centre of the Syriac Orthodox ... from the 6th to the early 9th century", when it was sacked and went into decline.

Jean de Vignay (c. 1282/1285 – c. 1350) was a French monk and translator. He translated from Latin into Old French for the French court, and his works survive in many illuminated manuscripts. They include two military manuals, a book on chess, parts of the New Testament, a travelogue and a chronicle.

William of Santo Stefano, in Italian Guglielmo di Santo Stefano, was an Italian nobleman, historian and patron of letters. He was an active member of the Knights Hospitaller in Outremer, northern Italy and Cyprus, where he was commander from at least 1299 until 1303.

Guy II or Guido II, surnamed Embriaco, was the lord of Gibelet from about 1271 until his death.

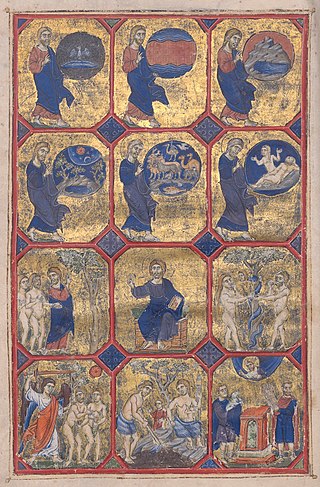

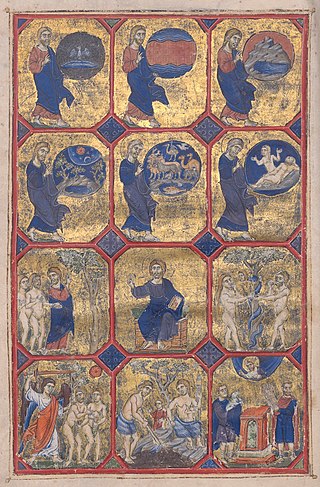

The Acre Bible is a partial Old French version of the Old Testament, containing both new and revised translations of 15 canonical and 4 deuterocanonical books, plus a prologue and glosses. The books are Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, Judith, Esther, Job, Tobit, Proverbs, 1 and 2 Maccabees and Ruth. It is an early and somewhat rough vernacular translation. Its version of Job is the earliest vernacular translation in Western Europe.

The fall of Outremer describes the history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem from the end of the last European Crusade to the Holy Land in 1272 until the final loss in 1302. The kingdom was the center of Outremer—the four Crusader states—formed after the First Crusade in 1099 and reached its peak in 1187. The loss of Jerusalem in that year began the century-long decline. The years 1272–1302 are fraught with many conflicts throughout the Levant as well as the Mediterranean and Western European regions, and many Crusades were proposed to free the Holy Land from Mamluk control. The major players fighting the Muslims included the kings of England and France, the kingdoms of Cyprus and Sicily, the three Military Orders and Mongol Ilkhanate. Traditionally, the end of Western European presence in the Holy Land is identified as their defeat at the Siege of Acre in 1291, but the Christian forces managed to hold on to the small island fortress of Ruad until 1302.