Artemisia Lomi or Artemisia Gentileschi was an Italian Baroque painter. Gentileschi is considered among the most accomplished 17th-century artists, initially working in the style of Caravaggio. She was producing professional work by the age of 15. In an era when women had few opportunities to pursue artistic training or work as professional artists, Gentileschi was the first woman to become a member of the Accademia di Arte del Disegno in Florence and she had an international clientele.

Orazio Lomi Gentileschi (1563–1639) was an Italian painter. Born in Tuscany, he began his career in Rome, painting in a Mannerist style, much of his work consisting of painting the figures within the decorative schemes of other artists.

Judith Beheading Holofernes is a painting of the biblical episode by Caravaggio, painted in c. 1598–1599 or 1602, in which the widow Judith stayed with the Assyrian general Holofernes in his tent after a banquet then decapitated him after he passed out drunk. The painting was rediscovered in 1950 and is part of the collection of the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica in Rome. The exhibition 'Dentro Caravaggio' Palazzo Reale, Milan, suggests a date of 1602 on account of the use of light underlying sketches not seen in Caravaggio's early work but characteristic of his later works. The exhibition catalogue also cites biographer artist Giovanni Baglione's account that the work was commissioned by Genoa banker Ottavio Costa.

The account of the beheading of Holofernes by Judith is given in the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, and is the subject of many paintings and sculptures from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the story, Judith, a beautiful widow, is able to enter the tent of Holofernes because of his desire for her. Holofernes was an Assyrian general who was about to destroy Judith's home, the city of Bethulia. Overcome with drink, he passes out and is decapitated by Judith; his head is taken away in a basket.

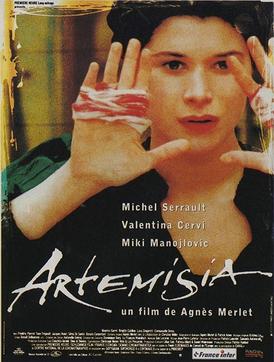

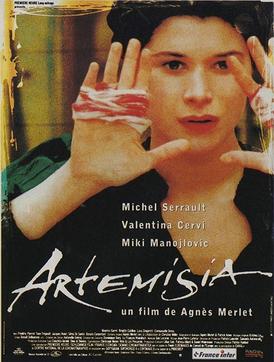

Artemisia is a 1997 French-German-Italian biographical film about Artemisia Gentileschi, the female Italian Baroque painter. The film was directed by Agnès Merlet, and stars Valentina Cervi and Michel Serrault.

Judith Slaying Holofernes is a painting by the Italian early Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi, completed in 1612-13 and now at the Museo Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting, also known as Autoritratto in veste di Pittura or simply La Pittura, was painted by the Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. The oil-on-canvas painting measures 98.6 by 75.2 centimetres and was probably produced during Gentileschi's stay in England between 1638 and 1639. It was in the collection of Charles I and was returned to the Royal Collection at the Restoration (1660) and remains there. In 2015 it was put on display in the "Cumberland Gallery" in Hampton Court Palace.

Judith and Holofernes may refer to:

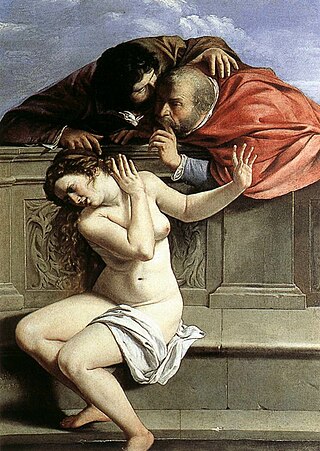

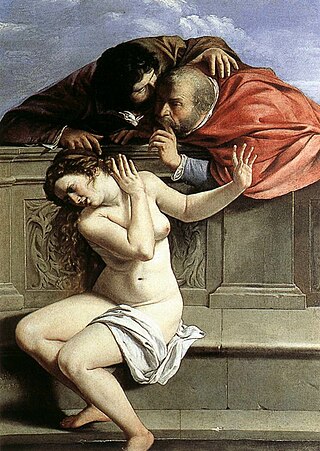

Susanna and the Elders is a 1610 painting by the Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi and is her earliest-known signed and dated work. It was one of Gentileschi's signature works. She painted several variations of the scene in her career. It hangs at Schloss Weißenstein in Pommersfelden, Germany. The work shows a frightened Susanna with two men lurking above her while she is in the bath. The subject matter comes from the deuterocanonical Book of Susanna in the Additions to Daniel. This was a popular scene to paint during the Baroque period.

Esther Before Ahasuerus is a painting by the 17th-century Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi. It shows the biblical heroine Esther going before Ahasuerus to beg him to spare her people. The painting is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, having been donated to the museum by Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll in 1969. It is one of Gentileschi's lesser known works, but her use of lighting, characterization, and style help in successfully portraying Esther as a biblical heroine as well as the main protagonist of the work.

Judith and her Maidservant is a c. 1615 painting by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. The painting depicts Judith and her maidservant leaving the scene where they have just beheaded general Holofernes, whose head is in the basket carried by the maidservant. It hangs in the Pitti Palace, Florence.

This is an ongoing bibliography of work related to the Italian baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi.

Self-Portrait as a Lute Player is one of many self-portrait paintings made by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. It was created between 1615 and 1617 for the Medici family in Florence. Today, it hangs in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, US. It shows the artist posing as a lute player looking directly at the audience. The painting has symbolism in the headscarf and outfit that portray Gentileschi in a costume that resembles a Romani woman. Self-Portrait as a Lute Player has been interpreted as Gentileschi portraying herself as a knowledgeable musician, a self portrayal as a prostitute, and as a fictive expression of one aspect of her identity.

Jael and Sisera is a painting by the Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi, executed around 1620.

Penitent Magdalene is a 1616–1618 painting by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. This painting hangs in the Pitti Palace in Florence. The subject is the biblical figure Mary Magdalene, but the painting references another biblical woman, Mary, the sister of Lazarus. This painting was likely painted during Gentileschi's Florentine period.

Saint Catherine of Alexandra is a painting by the Italian Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. It is in the collection of the Uffizi, Florence. Gentileschi likely used the same cartoon or preparatory drawing to create both this painting and the Self-Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria (1615–1617), now in the National Gallery, London.

Judith and Her Maidservant is a painting by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. Executed sometime between 1640 and 1645, it hangs in the Musée de la Castre in Cannes.

The Birth of Saint John the Baptist, by Artemisia Gentileschi, was part of a six-painting portrayal of Saint John's life, with four of the paintings by Massimo Stanzione and one by Paolo Finoglia, for the Hermitage of San Juan Bautista on the grounds of Buen Rierto in Madrid, under orders from the Viceroy of Naples, the Conde de Monterrey. Although a date has not been agreed upon by scholars, Artemesia most likely painted The Birth of Saint John the Baptist between 1633 and 1635. It is one of the most renowned works from Artemisia's Naples period, especially due to its detailed rendering of fabrics and floor tiles.

Judith Slaying Holofernes c. 1620, now at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, is the renowned painting by Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi depicting the assassination of Holofernes from the apocryphal Book of Judith. When compared to her earlier interpretation from Naples c. 1612, there are subtle but marked improvements to the composition and detailed elements of the work. These differences display the skill of a cultivated Baroque painter, with the adept use of chiaroscuro and realism to express the violent tension between Judith, Abra, and the dying Holofernes.

Susanna and the Elders is an Old Testament story of a woman falsely accused of adultery after she refuses two men who, after discovering one another in the act of spying on her while she bathes, conspire to blackmail her for sex. Depictions of the story date back to the late 3rd/early 4th centuries and are still being created.