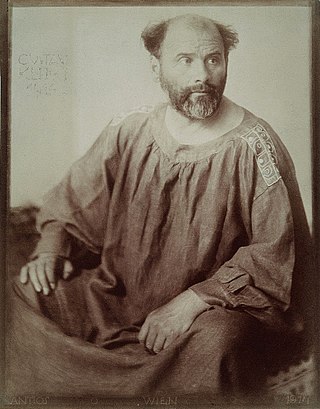

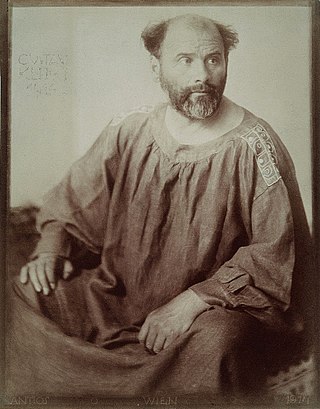

Gustav Klimt was an Austrian symbolist painter and one of the most prominent members of the Vienna Secession movement. Klimt is noted for his paintings, murals, sketches, and other objets d'art. Klimt's primary subject was the female body, and his works are marked by a frank eroticism. Amongst his figurative works, which include allegories and portraits, he painted landscapes. Among the artists of the Vienna Secession, Klimt was the most influenced by Japanese art and its methods.

The Book of Judith is a deuterocanonical book included in the Septuagint and the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christian Old Testament of the Bible but excluded from the Hebrew canon and assigned by Protestants to the apocrypha. It tells of a Jewish widow, Judith, who uses her beauty and charm to kill an Assyrian general who has besieged her city, Bethulia. With this act, she saves nearby Jerusalem from total destruction. The name Judith, meaning "praised" or "Jewess", is the feminine form of Judah.

Republic of Austria v. Altmann, 541 U.S. 677 (2004), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act, or FSIA, applies retroactively to acts prior to its enactment in 1976.

The Österreichische Galerie Belvedere is a museum housed in the Belvedere palace, in Vienna, Austria.

Maria Altmann was an Austrian-American Jewish refugee from Austria, who fled her home country after it was annexed to the Third Reich. She is noted for her ultimately successful legal campaign to reclaim from the Government of Austria five family-owned paintings by the artist Gustav Klimt that were stolen by the Nazis during World War II.

The Kiss is an oil-on-canvas painting with added gold leaf, silver and platinum by the Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt. It was painted at some point in 1907 and 1908, during the height of what scholars call his "Golden Period". It was exhibited in 1908 under the title Liebespaar as stated in the catalogue of the exhibition. The painting depicts a couple embracing each other, their bodies entwined in elaborate robes decorated in a style influenced by the contemporary Art Nouveau style and the organic forms of the earlier Arts and Crafts movement.

Hubertus Czernin was an Austrian investigative journalist.

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I is an oil painting on canvas, with gold leaf, by Gustav Klimt, completed between 1903 and 1907. The portrait was commissioned by the sitter's husband, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, a Viennese and Jewish banker and sugar producer. The painting was stolen by the Nazis in 1941 and displayed at the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere. The portrait is the final and most fully representative work of Klimt's golden phase. It was the first of two depictions of Adele by Klimt—the second was completed in 1912; these were two of several works by the artist that the family owned.

Adele Bloch-Bauer was a Viennese socialite, salon hostess, and patron of the arts from Austria-Hungary. A Jewish woman, she is most well known for being the subject of two of artist Gustav Klimt's paintings: Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II, and the fate of the paintings during and after the Nazi Holocaust. She has been called "the Austrian Mona Lisa."

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II is a 1912 painting by Gustav Klimt. The work is a portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1881–1925), a Vienna socialite who was a patron and close friend of Klimt.

The account of the beheading of Holofernes by Judith is given in the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, and is the subject of many paintings and sculptures from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. In the story, Judith, a beautiful widow, is able to enter the tent of Holofernes because of his desire for her. Holofernes was an Assyrian general who was about to destroy Judith's home, the city of Bethulia. Overcome with drink, he passes out and is decapitated by Judith; his head is taken away in a basket.

Judith Slaying Holofernes is a painting by the Italian early Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi, completed in 1612-13 and now at the Museo Capodimonte, Naples, Italy.

Salome, or possibly Judith with the Head of Holofernes, is an oil painting which is an early work by the Venetian painter of the late Renaissance, Titian. It is usually thought to represent Salome with the head of John the Baptist. It is usually dated to around 1515 and is now in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome. Like other paintings of this subject, it has sometimes been considered to represent Judith with the head of Holofernes, the other biblical incident found in art showing a female and a severed male head. Historically, the main figure has also been called Herodias, the mother of Salome.

Judith and Holofernes may refer to:

Woman in Gold is a 2015 biographical drama film directed by Simon Curtis and written by Alexi Kaye Campbell. The film stars Helen Mirren, Ryan Reynolds, Daniel Brühl, Katie Holmes, Tatiana Maslany, Max Irons, Charles Dance, Elizabeth McGovern, and Jonathan Pryce.

Anne-Marie O'Connor is an American journalist and writer who authored The Lady in Gold: The Extraordinary Tale of Gustav Klimt's Masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. This bestselling story is about the eight-year legal battle by Vienna emigre Maria Altmann, represented by Los Angeles attorney E. Randol Schoenberg, to reclaim five Gustav Klimt paintings from her native Austria. This saga that also inspired a Harvey Weinstein movie, Woman in Gold, in which Helen Mirren played Maria Altmann. One of the paintings, ''Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer'', sold for a record $135 million in 2006 to Ronald Lauder's Neue Galerie New York, where the painting is on view.

Stealing Klimt is a 2007 documentary film about Maria Altmann's attempt to recover five Gustav Klimt paintings stolen from her family by the Nazis in 1938, from Austria.

Judith and her Maidservant is a c. 1615 painting by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. The painting depicts Judith and her maidservant leaving the scene where they have just beheaded general Holofernes, whose head is in the basket carried by the maidservant. It hangs in the Pitti Palace, Florence.

Judith and Her Maidservant is one of four paintings by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi that depicts the biblical story of Judith and Holofernes. This particular work, executed in about 1623 to 1625, now hangs in the Detroit Institute of Arts. The narrative is taken from the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, in which Judith seduces and then murders the general Holofernes. This precise moment illustrates the maidservant Abra wrapping the severed head in a bag, moments after the murder, while Judith keeps watch. The other three paintings are now shown in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, and the Musée de la Castre in Cannes.