Manihot esculenta, commonly called cassava, manioc, or yuca, is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America, from Brazil and parts of the Andes. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated as an annual crop in tropical and subtropical regions for its edible starchy root tuber, a major source of carbohydrates. Cassava is predominantly consumed in boiled form, but substantial quantities are used to extract cassava starch, called tapioca, which is used for food, animal feed, and industrial purposes. The Brazilian farinha, and the related garri of West Africa, is an edible coarse flour obtained by grating cassava roots, pressing moisture off the obtained grated pulp, and finally drying it.

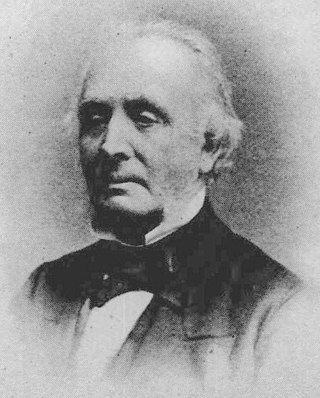

William Farr CB was a British epidemiologist, regarded as one of the founders of medical statistics.

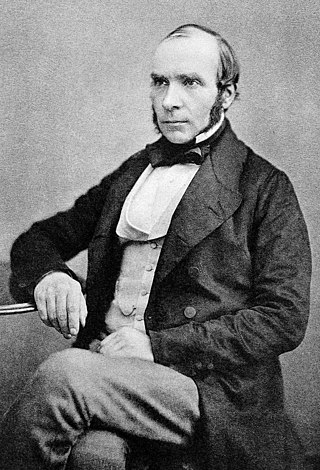

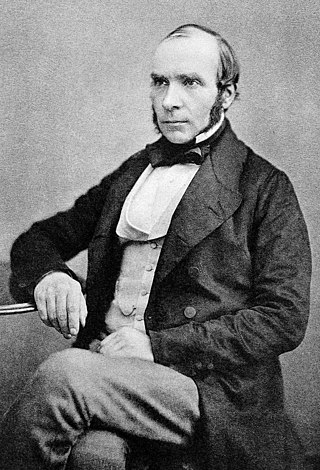

John Snow was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology and early germ theory, in part because of his work in tracing the source of a cholera outbreak in London's Soho, which he identified as a particular public water pump. Snow's findings inspired fundamental changes in the water and waste systems of London, which led to similar changes in other cities, and a significant improvement in general public health around the world.

Edward Headlam Greenhow FRS, FRCP was an English physician, epidemiologist, sanitarian, statistician, clinician and lecturer.

Hans Rosling was a Swedish physician, academic and public speaker. He was a professor of international health at Karolinska Institute and was the co-founder and chairman of the Gapminder Foundation, which developed the Trendalyzer software system. He held presentations around the world, including several TED Talks in which he promoted the use of data to explore development issues. His posthumously published book Factfulness, coauthored with his daughter-in-law Anna Rosling Rönnlund and son Ola Rosling, became an international bestseller.

Thomas Michael Greenhow MD MRCS FRCS was an English surgeon and epidemiologist.

Linamarin is a cyanogenic glucoside found in the leaves and roots of plants such as cassava, lima beans, and flax. It is a glucoside of acetone cyanohydrin. Upon exposure to enzymes and gut flora in the human intestine, linamarin and its methylated relative lotaustralin can decompose to the toxic chemical hydrogen cyanide; hence food uses of plants that contain significant quantities of linamarin require extensive preparation and detoxification. Ingested and absorbed linamarin is rapidly excreted in the urine and the glucoside itself does not appear to be acutely toxic. Consumption of cassava products with low levels of linamarin is widespread in the low-land tropics. Ingestion of food prepared from insufficiently processed cassava roots with high linamarin levels has been associated with dietary toxicity, particularly with the upper motor neuron disease known as konzo to the African populations in which it was first described by Trolli and later through the research network initiated by Hans Rosling. However, the toxicity is believed to be induced by ingestion of acetone cyanohydrin, the breakdown product of linamarin. Dietary exposure to linamarin has also been reported as a risk factor in developing glucose intolerance and diabetes, although studies in experimental animals have been inconsistent in reproducing this effect and may indicate that the primary effect is in aggravating existing conditions rather than inducing diabetes on its own.

Konzo is an epidemic paralytic disease occurring among hunger-stricken rural populations in Africa where a diet dominated by insufficiently processed cassava results in simultaneous malnutrition and high dietary cyanide intake. Konzo was first described by Giovanni Trolli in 1938 who compiled the observations from eight doctors working in the Kwango area of the Belgian Congo.

Professor Benjamin Oluwakayode Osuntokun, was a researcher and neurologist from Okemesi, Ekiti State, Nigeria. Known for discovering the cause of ataxic tropical neuropathy, he was a founding member of the Pan African Association of Neurological Sciences and an early advocate and researcher on tropical neurology.

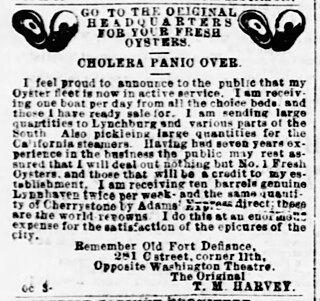

The third cholera pandemic (1846–1860) was the third major outbreak of cholera originating in India in the 19th century that reached far beyond its borders, which researchers at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) believe may have started as early as 1837 and lasted until 1863. In the Russian Empire, more than one million people died of cholera. In 1853–1854, the epidemic in London claimed over 10,000 lives, and there were 23,000 deaths for all of Great Britain. This pandemic was considered to have the highest fatalities of the 19th-century epidemics.

The fourth cholera pandemic of the 19th century began in the Ganges Delta of the Bengal region and traveled with Muslim pilgrims to Mecca. In its first year, the epidemic claimed 30,000 of 90,000 pilgrims. Cholera spread throughout the Middle East and was carried to the Russian Empire, Europe, Africa, and North America, in each case spreading via travelers from port cities and along inland waterways.

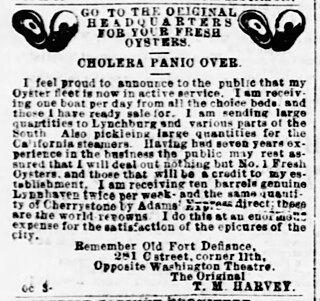

The Broad Street cholera outbreak was a severe outbreak of cholera that occurred in 1854 near Broad Street in Soho, London, England, and occurred during the 1846–1860 cholera pandemic happening worldwide. This outbreak, which killed 616 people, is best known for the physician John Snow's study of its causes and his hypothesis that germ-contaminated water was the source of cholera, rather than particles in the air. This discovery came to influence public health and the construction of improved sanitation facilities beginning in the mid-19th century. Later, the term "focus of infection" started to be used to describe sites, such as the Broad Street pump, in which conditions are favourable for transmission of an infection. Snow's endeavour to find the cause of the transmission of cholera caused him to unknowingly create a double-blind experiment.

Seven cholera pandemics have occurred in the past 200 years, with the first pandemic originating in India in 1817. The seventh cholera pandemic is officially a current pandemic and has been ongoing since 1961, according to a World Health Organization factsheet in March 2022. Additionally, there have been many documented major local cholera outbreaks, such as a 1991–1994 outbreak in South America and, more recently, the 2016–2021 Yemen cholera outbreak.

Health in Mozambique has a complex history, influenced by the social, economic, and political changes that the country has experienced. Before the Mozambican Civil War, healthcare was heavily influenced by the Portuguese. After the civil war, the conflict affected the country's health status and ability to provide services to its people, breeding the host of health challenges the country faces in present day.

Sarah Cleaveland is a veterinary surgeon and Professor of Comparative Epidemiology at the University of Glasgow.

Nazira Karimo Vali Abdula is a pediatrician and politician from Mozambique. She has served as Minister of Health in the government of Filipe Nyusi since January 19, 2015.

In the mid to late nineteenth century, scientific patterns emerged which contradicted the widely held miasma theory of disease. These findings led medical science to what we now know as the germ theory of disease. The germ theory of disease proposes that invisible microorganisms are the cause of particular illnesses in both humans and animals. Prior to medicine becoming hard science, there were many philosophical theories about how disease originated and was transmitted. Though there were a few early thinkers that described the possibility of microorganisms, it was not until the mid to late nineteenth century when several noteworthy figures made discoveries which would provide more efficient practices and tools to prevent and treat illness. The mid-19th century figures set the foundation for change, while the late-19th century figures solidified the theory.

The John Snow, formerly the Newcastle-upon-Tyne, is a public house in Broadwick Street, in the Soho district of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London, and dates back to the 1870s. It is named for the British epidemiologist and anaesthetist John Snow, who identified the nearby water pump as the source of a cholera outbreak in 1854.

The John Snow Society (JSS), founded 1992, is a learned society named for the English physician John Snow. It publishes the newsletter Broad Sheet, and hosts the Pumphandle Lecture at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The John Snow pub in Soho, London, serves as its meeting place.

The Pumphandle Lecture, established in 1993, is an annual lecture held around September to celebrate the removal of the Broad Street pump handle that took place in September 1854 during the cholera epidemic in Soho. It is organised by the John Snow Society, named for John Snow, and takes place at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.