Life and work

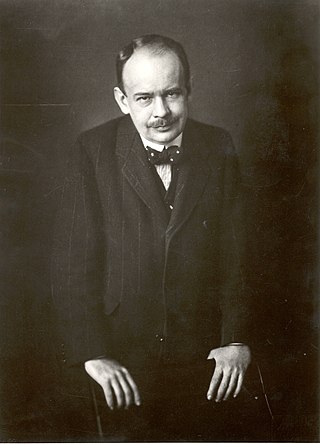

From 1884 to 1887, Julius Schlosser studied philology, art history and archaeology at the University of Vienna. [2] In 1888, he completed a Ph.D. thesis on early medieval cloisters supervised by Franz Wickhoff. In 1892, he wrote his Habilitationsschrift. In 1901, he was appointed professor and director of the sculpture collection at Vienna. In 1913, he was knighted and changed his name from Julius Schlosser to Julius von Schlosser. In 1919 he became member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. After the unexpected death of Max Dvořák in 1922, he chaired the second art history department of the University of Vienna, his colleague, and opponent, Josef Strzygowski chairing the first art history department. [3] [4] [5] Von Schlosser retired in 1936.

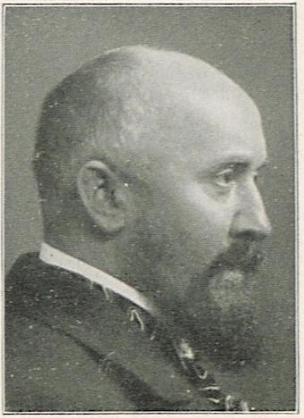

In 1908, Von Schlosser published Die Kunst- und Wunderkammern der Spätrenaissance, and in 1912 a study on Lorenzo Ghiberti's memoirs. [6] From 1914 to 1920, he wrote his eight-part Materialien zur Quellenkunde der Kunstgeschichte, and in 1923 a study on medieval art, entitled Die Kunst des Mittelalters. In 1924, he published Die Kunstliteratur, a bibliography on writings on art, which was translated into Italian as La letteratura artistica: Manuale delle fonti della storia dell'arte moderna (1935; 2nd edition, 1956; 3rd edition, 1964). [7] [8] In 1984, it was also translated into French. [9] This publication, which expressed discontent with Jacob Burckhardt's assessments in Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien (1860) on several counts, [10] is a "famous standard work ... which is still the most admirable survey of writings about art from antiquity to the eighteenth century". [4] "Written with the profound insight of first-hand knowledge, it is not only indispensable as a bibliographical reference book, but it is also one of the few works in our subject to be both genuinely scholarly and readable." [11]

From 1929 to 1934, his 3-volume Künstlerprobleme der Frührenaissance appeared. This was followed by a study on Die Wiener Schule der Kunstgeschichte (1934, translated into English as The Vienna School of Art History), in which, however, he contemptuously claimed that the first art history department at the University of Vienna, chaired by his opponent Strzygowski, had nothing in common with the Vienna School and indeed often contradicted it, so that he completely omitted it from his historical sketch. [12] [13] In 1941, a posthumous monograph on Ghiberti appeared. In 1998, his "Geschichte der Porträtbildnerei in Wachs" (1911) was translated into English. [14] Besides his art historical writings, Von Schlosser also published a history of musical instruments (1922).

His mother being of Italian ancestry, [2] he spoke Italian very well and expected his students to read original Italian texts, particularly Vasari. [4] Being a close friend of Benedetto Croce, Von Schlosser translated the works of the famous Italian philosopher into German.

According to Catherine M. Soussloff, "much of von Schlosser's work raises a question basic to any discourse on visual culture, such as art history, that constructs the maker as essential to an understanding of the artifact or object. Can the biography of an artist be held in a privileged and isolated status from the other written sources ...? This question cannot be answered adequately without looking more closely at the arguments found in von Schlosser concerning the structure of the biography of the artist that later informed those of Legend, Myth, and Magic.". [15]

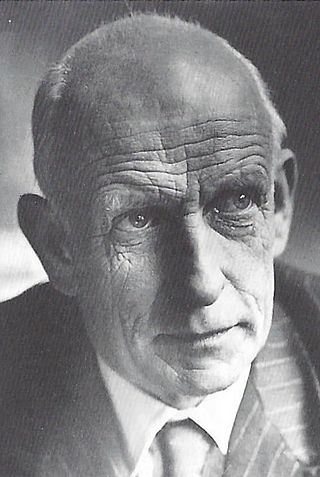

In his obituary in the Burlington Magazine, Ernst Gombrich emphasizes that Von Schlosser "was not a specialist of the modern type — nor did he ever strive to be one. For any kind of specialisation his reading was too vast, his outlook too broad, his horizon too wide. It embraced literature no less than art and history and last, but not least — music. His horror of professionalism of any kind is reflected in every single line he wrote." [16] According to the Dictionary of Art Historians, he is "considered one of the giants of the discipline of art history in the twentieth century". [17]

Von Schlosser's students included Ernst Kris, Otto Kurz, Ernst Gombrich, Otto Pächt, Hans Sedlmayr, Fritz Saxl, Ludwig Goldscheider, Charles de Tolnay, and other well-known art historians. [17]

The Schlossergasse in Vienna was named in honor of Julius von Schlosser's memory. [18]