A loom is a device used to weave cloth and tapestry. The basic purpose of any loom is to hold the warp threads under tension to facilitate the interweaving of the weft threads. The precise shape of the loom and its mechanics may vary, but the basic function is the same.

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Normally it is used to create images rather than patterns. Tapestry is relatively fragile, and difficult to make, so most historical pieces are intended to hang vertically on a wall, or sometimes horizontally over a piece of furniture such as a table or bed. Some periods made smaller pieces, often long and narrow and used as borders for other textiles. Most weavers use a natural warp thread, such as wool, linen, or cotton. The weft threads are usually wool or cotton but may include silk, gold, silver, or other alternatives.

A carpet is a textile floor covering typically consisting of an upper layer of pile attached to a backing. The pile was traditionally made from wool, but since the 20th century synthetic fibers such as polypropylene, nylon, or polyester have often been used, as these fibers are less expensive than wool. The pile usually consists of twisted tufts that are typically heat-treated to maintain their structure. The term carpet is often used in a similar context to the term rug, but rugs are typically considered to be smaller than a room and not attached to the floor.

Ikat is a dyeing technique from Southeast Asia used to pattern textiles that employs resist dyeing on the yarns prior to dyeing and weaving the fabric. In Southeast Asia, where it is the most widespread, ikat weaving traditions can be divided into two general groups of related traditions. The first is found among Daic-speaking peoples. The second, larger group is found among the Austronesian peoples and spread via the Austronesian expansion to as far as Madagascar. It is most prominently associated with the textile traditions of Indonesia in modern times, from where the term ikat originates. Similar unrelated dyeing and weaving techniques that developed independently are also present in other regions of the world, including India, Central Asia, Japan, Africa, and the Americas.

A Persian carpet, Persian rug, or Iranian carpet is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in Iran, for home use, local sale, and export. Carpet weaving is an essential part of Persian culture and Iranian art. Within the group of Oriental rugs produced by the countries of the "rug belt", the Persian carpet stands out by the variety and elaborateness of its manifold designs.

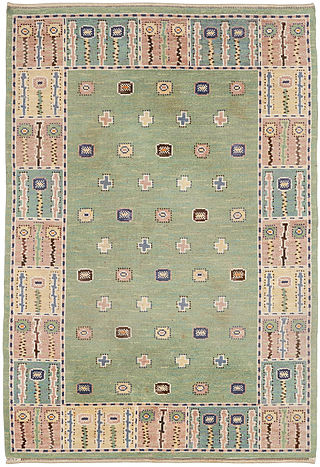

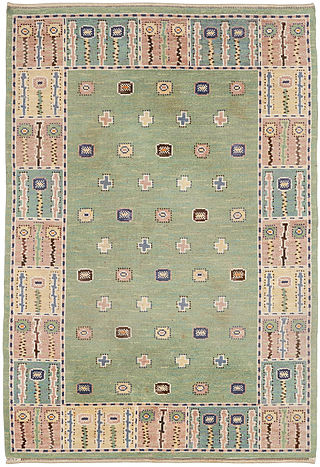

A kilim is a flat tapestry-woven carpet or rug traditionally produced in countries of the former Persian Empire, including Iran, but also in the Balkans and the Turkic countries. Kilims can be purely decorative or can function as prayer rugs. Modern kilims are popular floor coverings in Western households.

Knot density is a traditional measure for quality of handmade or knotted pile carpets. It refers to the number of knots, or knot count, per unit of surface area - typically either per square inch (kpsi) or per square centimeter (kpsc), but also per decimeter or meter. Number of knots per unit area is directly proportional to the quality of carpet. Density may vary from 25 to 1,000 knots per square inch or higher, where ≤80 kpsi is poor quality, 120 to 330 kpsi is medium to good, and ≥330 kpsi is very good quality. The inverse, knot ratio, is also used to compare characteristics. Knot density = warp×weft while knot ratio = warp/weft. For comparison: 100,000/square meter = 1,000/square decimeter = 65/square inch = 179/gereh.

Paithani is a variety of sari, named after the Paithan town in Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district from state of Maharashtra in India where the sari was first made by hand. Present day Yeola town in Nashik, Maharashtra is the largest manufacturer of Paithani.

An oriental rug is a heavy textile made for a wide variety of utilitarian and symbolic purposes and produced in "Oriental countries" for home use, local sale, and export.

Anatolian rug or Turkish carpet is a term of convenience, commonly used today to denote rugs and carpets woven in Anatolia and its adjacent regions. Geographically, its area of production can be compared to the territories which were historically dominated by the Ottoman Empire. It denotes a knotted, pile-woven floor or wall covering which is produced for home use, local sale, and export, and religious purpose. Together with the flat-woven kilim, Anatolian rugs represent an essential part of the regional culture, which is officially understood as the Culture of Turkey today, and derives from the ethnic, religious and cultural pluralism of one of the most ancient centres of human civilisation.

The manufacture of textiles is one of the oldest of human technologies. To make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fiber from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. The yarn is processed by knitting or weaving, which turns it into cloth. The machine used for weaving is the loom. For decoration, the process of colouring yarn or the finished material is dyeing. For more information of the various steps, see textile manufacturing.

A knotted-pile carpet is a carpet containing raised surfaces, or piles, from the cut off ends of knots woven between the warp and weft. The Ghiordes/Turkish knot and the Senneh/Persian knot, typical of Anatolian carpets and Persian carpets, are the two primary knots. A flat or tapestry woven carpet, without pile, is a kilim. A pile carpet is influenced by width and number of warp and weft, pile height, knots used, and knot density.

Pile is the raised surface or nap of a fabric, consisting of upright loops or strands of yarn. Examples of pile textiles are carpets, corduroy, velvet, plush, and Turkish towels (terrycloth). The word is derived from Latin pilus for "hair".

A Turkmen rug is a type of handmade floor-covering textile traditionally originating in Central Asia. It is useful to distinguish between the original Turkmen tribal rugs and the rugs produced in large numbers for export mainly in Pakistan and Iran today. The original Turkmen rugs were produced by the Turkmen tribes who are the main ethnic group in Turkmenistan and are also found in Afghanistan and Iran. They are used for various purposes, including tent rugs, door hangings and bags of various sizes.

Soumak is a tapestry technique of weaving sturdy, decorative fabrics used for carpets, rugs, domestic bags and bedding, with soumak fabrics used for bedding known as soumak mafrash.

Bhutanese textiles represent a rich and complex repository of a unique art form. They are recognised for their abundance of colour, sophistication and variation of patterns, and the intricate dyeing and weaving techniques. The weavers, who are mostly women, must not be seen merely as creators of wealth but also as the innovators and owners of artistic skills developed and nurtured over centuries of time.

Scandinavia has a long and proud tradition of rug-making on par with many of the regions of the world that are perhaps more immediately associated with the craft—regions such as China and Persia. Rugs have been handmade by craftspeople in the Scandinavian countries of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden for centuries, and have often played important cultural roles in each of these countries. Contemporary Scandinavian rugs—most especially Swedish rugs—are among the most sought after rugs in the world today, largely due to the contributions of designers like Märta Måås-Fjetterström. The story of Scandinavian rugs is a vital chapter in the cultural study of Scandinavia, as it reveals a great deal about the aesthetic and social conventions of that region.

Carpets and rugs have been handmade in Sweden for centuries, taking on many different forms and functions over the course of time. Rugs woven in the traditional Oriental manner, especially in the Ottoman Empire and points east, were originally brought to Sweden over trade routes as early as the early Middle Ages. In the centuries that followed, Swedish rug-makers often infused their works with themes and motifs traditionally found in Oriental rugs. Eventually, Swedish rug-makers would begin to use Oriental rug-making techniques, but themes and motifs more consistent with the artistic and cultural heritage of Sweden. By the early modern periods, rugs had long been an important avenue of art – especially folk art – in Swedish culture. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the craft was seen as being an important artistic and cultural practice throughout Sweden, and designers began to make rugs that had a broad international appeal. Swedish rugs from the mid-twentieth century remain among the most desirable and sought after in the rug world.

A lazy line or section line is a technical feature of weaving which describes visible diagonal joins within a woven textile. It results from interlacing wefts joining adjacent warp sections woven at different times. Successive rows of turnarounds of discontinuous wefts create a diagonal line which, in pile rugs, is best seen from the back side, and from the front side only if the pile is heavily worn. A lazy line is created when the weaver does not finish a rug line by line from one side to the other, but sequentially finishes one area after the other.

Meisen is a type of silk fabric traditionally produced in Japan; it is durable, hard-faced, and somewhat stiff, with a slight sheen, and slubbiness is deliberately emphasised. Meisen was first produced in the late 19th century, and became widely popular during the 1920s and 30s, when it was mass-produced and ready-to-wear kimono began to be sold in Japan. Meisen is commonly dyed using kasuri techniques, and features what were then overtly modern, non-traditional designs and colours. Meisen remained popular through to the 1950s.