Background

Derrick Kimbrough was indicted in September 2004 in federal court in Virginia on four drug-related counts: conspiracy to distribute both crack and powder cocaine; possession with intent to distribute more than 50 grams of crack cocaine; possession with intent to distribute powder cocaine; and possession of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking offense. Kimbrough pleaded guilty to all four counts. Under the statutes that define these respective crimes, Kimbrough faced a sentence of between 15 years and life in prison. Based on the facts, Kimbrough admitted at his change-of-plea hearing, as well as the fact that Kimbrough had testified falsely at a codefendant's trial, the district court computed the applicable range under the federal sentencing guidelines at 18 to 22.5 years in prison.

Kimbrough's Guidelines range was so high because his offense involved both crack and powder cocaine. US District Court Judge Raymond Alvin Jackson observed that if Kimbrough's crime had involved powder cocaine only, his sentencing range would have been 97 to 106 months. The mandatory minimum sentence, in turn, was 180 months in prison, and the district judge imposed that sentence. Kimbrough was represented by Assistant Federal Public Defender Riley H. Ross III. The government was represented by Assistant United States Attorney William D. Murh.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals vacated the sentence and remanded for further proceedings. Relying on a prior opinion, the appellate court stated that any sentence that fell outside the Guidelines range was per se unreasonable if that sentence was based on a policy disagreement with the fact that crack cocaine offenses are punished more harshly than powder cocaine offenses. The United States Supreme Court agreed to review the Fourth Circuit's reasoning in this case.

Majority opinion

Under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, a drug trafficker dealing in crack cocaine is subject to the same sentence as one who trafficks in 100 times as much powder cocaine. The two drugs are chemically similar; they produce the same high, although the modes of ingestion differ. The result of the 100-to-1 ratio is that sentences for crack cocaine offenders are three to six times longer than those for powder cocaine offenders. As the United States Sentencing Commission concluded in a 2002 report, a "major supplier of powder cocaine may receive a shorter sentence than a low-level dealer who buys powder from the supplier but then converts it into crack" cocaine.

In the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, heroin received a 10-to-1 ratio. Defendants responsible for 100 grams of heroin were subject to a five-year mandatory minimum, but defendants responsible for 1000 grams were subject to a ten-year mandatory minimum sentence. However, the Act imposed a 100-to-1 ratio for powder to crack cocaine. The same five-year mandatory minimum sentence applies to defendants who are held responsible for either 500 grams of powder cocaine or 5 grams of crack. The ten-year mandatory minimum applied to defendants responsible for either 5000 grams of powder cocaine or 50 grams of crack. The Sentencing Commission followed this approach when fixing penalties for powder and crack cocaine, even as it relied on empirical evidence culled from actual sentences imposed in other kinds of criminal cases to formulate the new Sentencing Guidelines.

Later, however, the Sentencing Commission came to the conclusion that the 100-to-1 ratio was "generally unwarranted." The ratio rests on unwarranted assumptions about the relative harmfulness of the two forms of the drugs. Crack cocaine was associated with "significantly less trafficking-related violence than previously assumed." It is no more harmful to developing fetuses than powder cocaine. The epidemic of crack addiction that had been feared in 1986 failed to materialize. Moreover, the 100-to-1 ratio indeed had the effect of punishing low-level dealers more harshly than major traffickers, because it was the low-level dealers and not the traffickers who converted the powder cocaine into crack. Finally, the ratio promoted widespread disrespect and distrust in the criminal justice system, especially because it promoted a racial discrepancy between the sentences imposed on cocaine defendants. Powder cocaine defendants tend to be white and receive shorter sentences than crack cocaine defendants, who tend to be black.

In 1995, the Commission proposed reducing the ratio to 1-to-1 and adding other enhancements targeted at crack cocaine crimes involving violence. Congress exercised its statutory authority to overrule this proposal. Undaunted, the Commission recommended reducing the ratio twice more—to 5-to-1 in 1997, and to 20-to-1 in 2002. Congress ignored these proposals. In 2006, the Commission unilaterally altered the sentencing ranges associated with crack cocaine, achieving in effect a 10-to-1 ratio in sentencing quantities. At the same time, however, it urged Congress to adopt a more comprehensive solution.

With the Court's decision in United States v. Booker , 543 U.S. 220 (2005), which made the then-mandatory Guidelines "effectively advisory," district courts were again free to impose sentences that took into account the "history and characteristics of the defendant," the "nature and circumstances of the offense," disparities in sentences that might be "unwarranted," and other factors to fashion a sentence that is "sufficient but not greater than necessary" to achieve the overall goals of sentencing. Even though the commission had implemented the ratio in the Guidelines, the Government contended that the commission could not alter the 100-to-1 ratio because that was a policy choice that Congress had required the commission to implement. The Court rejected this argument for three reasons.

First, it lacked any foundation in the text of the 1986 Anti-Drug Act. Hence, if before Booker the Act could not require the Commission to implement any particular ratio, it cannot impose the same requirement on sentencing judges after Booker.

Second, the fact that in 1995 Congress disapproved the commission's effort to impose a 1-to-1 ratio did not mean that Congress meant for the 100-to-1 ratio to apply in perpetuity. Indeed, when the Commission effectively changed the ratio to 10-to-1, Congress did not disapprove.

Third, "as we explained in Booker, advisory Guidelines combined with appellate review for reasonableness and ongoing revision of the Guidelines in response to sentencing practices" will help to avoid disparities that might result from relaxing the 100-to-1 ratio. Accordingly, the Court affirmed the 180-month sentence the district court had imposed on Kimbrough.

The war on drugs is a global anti-narcotics campaign led by the United States federal government, including drug prohibition, foreign assistance, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the US. The initiative includes a set of drug policies that are intended to discourage the production, distribution, and consumption of psychoactive drugs that the participating governments, through United Nations treaties, have made illegal.

The United States Federal Sentencing Guidelines are rules published by the U.S. Sentencing Commission that set out a uniform policy for sentencing individuals and organizations convicted of felonies and serious misdemeanors in the United States federal courts system. The Guidelines do not apply to less serious misdemeanors or infractions.

Mandatory sentencing requires that people convicted of certain crimes serve a predefined term of imprisonment, removing the discretion of judges to take issues such as extenuating circumstances and a person's likelihood of rehabilitation into consideration when sentencing. Research shows the discretion of sentencing is effectively shifted to prosecutors, as they decide what charges to bring against a defendant. Mandatory sentencing laws vary across nations; they are more prevalent in common law jurisdictions because civil law jurisdictions usually prescribe minimum and maximum sentences for every type of crime in explicit laws. They can be applied to crimes ranging from minor offences to extremely violent crimes including murder.

United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005), is a United States Supreme Court decision on criminal sentencing. The Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment right to jury trial requires that other than a prior conviction, only facts admitted by a defendant or proved beyond a reasonable doubt to a jury may be used to calculate a sentence exceeding the prescribed statutory maximum sentence, whether the defendant has pleaded guilty or been convicted at trial. The maximum sentence that a judge may impose is based upon the facts admitted by the defendant or proved to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt.

The crack epidemic was a surge of crack cocaine use in major cities across the United States throughout the entirety of the 1980s and the early 1990s. This resulted in a number of social consequences, such as increasing crime and violence in American inner city neighborhoods, a resulting backlash in the form of tough on crime policies, and a massive spike in incarceration rates.

Bailey v. United States, 516 U.S. 137 (1995), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court interpreted a frequently used section of the federal criminal code. At the time of the decision, 18 U.S.C. § 924(c) imposed a mandatory, consecutive five-year prison term on anyone who "during and in relation to any... drug trafficking crime... uses a firearm." The lower court had sustained the defendants' convictions, defining "use" in such a way as to mean little more than mere possession. The Supreme Court ruled instead that "use" means "active employment" of a firearm, and sent the cases back to the lower court for further proceedings. As a result of the Court's decision in Bailey, Congress amended the statute to expressly include possession of a firearm as requiring the additional five-year prison term.

Rita v. United States, 551 U.S. 338 (2007), was a United States Supreme Court case that clarified how federal courts of appeals should implement the remedy for the Sixth Amendment violation identified in United States v. Booker. In Booker, the Court held that because the Federal Sentencing Guidelines were mandatory and binding on judges in criminal cases, the Sixth Amendment required that any fact necessary to impose a sentence above the top of the authorized Guidelines range must be found by a jury beyond a reasonable doubt. The Booker remedy made the Guidelines merely advisory and commanded federal appeals courts to review criminal sentences for "reasonableness." Rita clarified that a sentence within the Guidelines range may be presumed "reasonable."

William Spade is an American criminal defense attorney in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His clients have included Corey Kemp, the former Treasurer of the City of Philadelphia, who was prosecuted by the United States Department of Justice for honest services fraud, Julius Murray, a private social worker, charged with involuntary manslaughter in the death of 14-year-old Danieal Kelly, who was allegedly starved to death by her mother, Andrea Kelly, and Kevin Felder, who was charged with capital murder in the shooting death of five-year-old Casha'e Rivers, but ultimately cleared.

Mark Warren Bennett is a former United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Iowa and a professor at Drake University Law School.

The War on Drugs is a term for the actions taken and legislation enacted by the US federal government, intended to reduce or eliminate the production, distribution, and use of illicit drugs. The War on Drugs began during the Nixon administration with the goal of reducing the supply of and demand for illegal drugs, but an ulterior racial motivation has been proposed. The War on Drugs has led to controversial legislation and policies, including mandatory minimum penalties and stop-and-frisk searches, which have been suggested to be carried out disproportionately against minorities. The effects of the War on Drugs are contentious, with some suggesting that it has created racial disparities in arrests, prosecutions, imprisonment, and rehabilitation. Others have criticized the methodology and the conclusions of such studies. In addition to disparities in enforcement, some claim that the collateral effects of the War on Drugs have established forms of structural violence, especially for minority communities.

United States federal probation and supervised release are imposed at sentencing. The difference between probation and supervised release is that the former is imposed as a substitute for imprisonment, or in addition to home detention, while the latter is imposed in addition to imprisonment. Probation and supervised release are both administered by the U.S. Probation and Pretrial Services System. Federal probation has existed since 1909, while supervised release has only existed since 1987, when it replaced federal parole as a means for imposing supervision following release from prison.

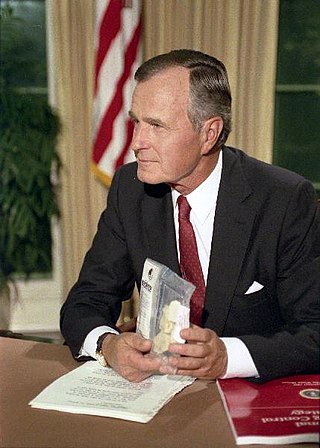

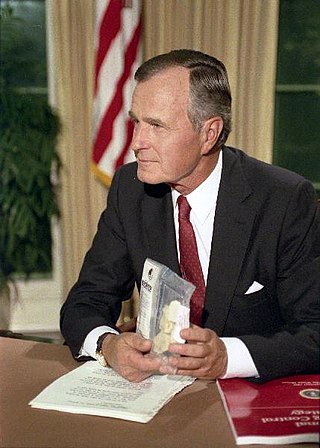

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 was a law pertaining to the War on Drugs passed by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by U.S. President Ronald Reagan. Among other things, it changed the system of federal supervised release from a rehabilitative system into a punitive system. The 1986 Act also prohibited controlled substance analogs. The bill enacted new mandatory minimum sentences for drugs, including marijuana.

The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 was an Act of Congress that was signed into federal law by United States President Barack Obama on August 3, 2010, that reduces the disparity between the amount of crack cocaine and powder cocaine needed to trigger certain federal criminal penalties from a 100:1 weight ratio to an 18:1 weight ratio and eliminated the five-year mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack cocaine, among other provisions. Similar bills were introduced in several U.S. Congresses before its passage in 2010, and courts had also acted to reduce the sentencing disparity prior to the bill's passage.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 is a major law of the War on Drugs passed by the U.S. Congress which did several significant things:

- Created the policy goal of a drug-free America;

- Established the Office of National Drug Control Policy; and

- Restored the use of the death penalty by the federal government.

The Drug Trafficking Safe Harbor Elimination Act was a bill proposed to the 112th United States Congress in 2011. It was introduced to amend Section 846 of the Controlled Substances Act to close a loophole that has allowed many drug trafficking conspirators to avoid federal prosecution. The Drug Trafficking Safe Harbor Elimination Act would have made it a federal crime for persons who conspire on United States soil to traffic or aid and abet drug trafficking inside or even outside the borders of the United States. This Act was created to provide clarity to current laws within the United States and provide criminal prosecution of those who are involved in drug trafficking within the United States or outside its borders. This Act would have provided a borderless application to United States Law and extends possible criminal charges to all individuals involved in the drug transport. The bill passed the House but was not acted upon by the Senate and thus died.

Dorsey v. United States, 567 U.S. 260 (2012), is a Supreme Court of the United States decision in which the Court held that reduced mandatory minimum sentences for "crack cocaine" under the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 does apply to defendants who committed a crime before the Act went into effect but who were sentenced after that date. The Act's silence on how to apply its new rules, before the effective date or not, caused a split among the Justices on how to interpret its new lenient provisions. Specifically, the case centered on Edward Dorsey, a prior offender who had been convicted of possession before the new rules came into effect but was sentenced after the effective date.

The Smarter Sentencing Act is a bill in the United States Senate that would reduce mandatory minimum sentences for some federal drug offenses. In some cases, the new minimums would apply retroactively, giving some people currently in prison on drug offenses a new sentence.

Shular v. United States, 589 U.S. ___ (2020), is an opinion of the United States Supreme Court in which the Court held that, under the Armed Career Criminal Act of 1984, the definition of “serious drug offense” only requires that the state offense involve the conduct specified in the statute. Unlike other provisions of the ACCA, it does not require that state courts develop “generic” version of a crime, which describe the elements of the offense as they are commonly understood, and then compare the crime being charged to that generic version to determine whether the crime qualifies under the ACCA for purposes of penalty enhancement. The decision states that offenses defined under the ACCA are "unlikely names for generic offenses," and are therefore unambiguous. This renders the rule of lenity inapplicable.

Terry v. United States, 593 U.S. ___ (2021), was a United States Supreme Court case dealing with retroactive changes to prison sentences for drug-possession crimes related to the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, its retroactive nature established by the First Step Act of 2018. In a unanimous judgement, the Court ruled that while the First Step Act does allow for retroactive considerations of sentence reductions for drug-possession crimes prior to 2010, this only covers those that were sentenced under minimum sentencing requirements.

Concepcion v. United States, 597 U.S. ___ (2022), is a United States Supreme Court decision that concerns district courts' ability to consider changes of law or fact in exercising their discretion to reduce a sentence.