Richard Buckminster Fuller was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more than 30 books and coining or popularizing such terms as "Spaceship Earth", "Dymaxion", "ephemeralization", "synergetics", and "tensegrity".

A geodesic dome is a hemispherical thin-shell structure (lattice-shell) based on a geodesic polyhedron. The rigid triangular elements of the dome distribute stress throughout the structure, making geodesic domes able to withstand very heavy loads for their size.

Tensegrity, tensional integrity or floating compression is a structural principle based on a system of isolated components under compression inside a network of continuous tension, and arranged in such a way that the compressed members do not touch each other while the prestressed tensioned members delineate the system spatially.

In architecture and structural engineering, a space frame or space structure is a rigid, lightweight, truss-like structure constructed from interlocking struts in a geometric pattern. Space frames can be used to span large areas with few interior supports. Like the truss, a space frame is strong because of the inherent rigidity of the triangle; flexing loads are transmitted as tension and compression loads along the length of each strut.

In architecture, functionalism is the principle that buildings should be designed based solely on their purpose and function. An international functionalist architecture movement emerged in the wake of World War I, as part of the wave of Modernism. Its ideas were largely inspired by a desire to build a new and better world for the people, as broadly and strongly expressed by the social and political movements of Europe after the extremely devastating world war. In this respect, functionalist architecture is often linked with the ideas of socialism and modern humanism.

Environmental design is the process of addressing surrounding environmental parameters when devising plans, programs, policies, buildings, or products. It seeks to create spaces that will enhance the natural, social, cultural and physical environment of particular areas. Classical prudent design may have always considered environmental factors; however, the environmental movement beginning in the 1940s has made the concept more explicit.

Archigram was an avant-garde British architectural group whose unbuilt projects and media-savvy provocations "spawned the most influential architectural movement of the 1960's," according to Peter Cook, in the Princeton Architectural Press study Archigram (1999). Neofuturistic, anti-heroic, and pro-consumerist, the group drew inspiration from technology in order to create a new reality that was expressed through hypothetical projects, i.e., its buildings were never built, although the group did produce what the architectural historian Charles Jencks called "a series of monumental objects (one hesitates in calling them buildings since most of them moved, grew, flew, walked, burrowed or just sank under the water." The works of Archigram had a neofuturistic slant, influenced by Antonio Sant'Elia's works. Buckminster Fuller and Yona Friedman were also important sources of inspiration.

An active structure is a mechanical structure with the ability to alter its configuration, form or properties in response to changes in the environment.

Chuck Hoberman is an artist, engineer, architect, and inventor of folding toys and structures, most notably the Hoberman sphere.

Neo-futurism is a late-20th to early-21st-century movement in the arts, design, and architecture.

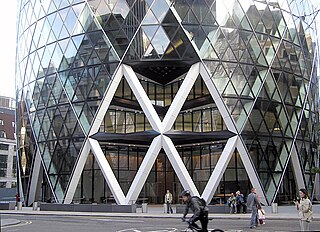

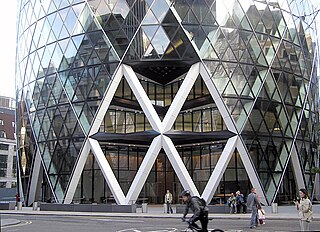

A diagrid is a framework of diagonally intersecting metal, concrete, or wooden beams that is used in the construction of buildings and roofs. It requires less structural steel than a conventional steel frame. Hearst Tower in New York City, designed by Norman Foster, uses 21 percent less steel than a standard design. The diagrid obviates the need for columns and can be used to make large column-free expanses of roofing. Another iconic building designed by Foster, 30 St Mary Axe, in London, UK, known as "The Gherkin", also uses the diagrid system.

High-tech architecture, also known as structural expressionism, is a type of late modernist architecture that emerged in the 1970s, incorporating elements of high tech industry and technology into building design. High-tech architecture grew from the modernist style, utilizing new advances in technology and building materials. It emphasizes transparency in design and construction, seeking to communicate the underlying structure and function of a building throughout its interior and exterior. High-tech architecture makes extensive use of aluminium, steel, glass, and to a lesser extent concrete, as these materials were becoming more advanced and available in a wider variety of forms at the time the style was developing – generally, advancements in a trend towards lightness of weight.

Gerald Gladstone was a Canadian sculptor and painter.

Responsive architecture is an evolving field of architectural practice and research. Responsive architectures are those that measure actual environmental conditions to enable buildings to adapt their form, shape, color or character responsively.

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings or other structures. The term comes from Latin architectura; from Ancient Greek ἀρχιτέκτων (arkhitéktōn) 'architect'; from ἀρχι- (arkhi-) 'chief' and τέκτων (téktōn) 'creator'. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural symbols and as works of art. Historical civilisations are often identified with their surviving architectural achievements.

Site-specific architecture (SSA) is architecture which is of its time and of its place. It is designed to respond to both its physical context, and the metaphysical context within which it has been conceived and executed. The physical context will include its location, local materials, planning framework, building codes, whilst the metaphysical context will include the client's aspirations, community values, and architects ideas about the building type, client, location, building use, etc.

William Zuk was an American engineer, architect, author, teacher, and futurist. After serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II, Zuk taught at the University of Virginia for 37 years. His career there began in the Civil Engineering school in 1958. In 1964 he transferred to the School of Architecture, where he taught structures until 1992, retiring as Professor Emeritus.

Domes built in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries benefited from more efficient techniques for producing iron and steel as well as advances in structural analysis.

Hajime Narukawa is a Japanese architect. He was born in 1971 in Kawasaki, Kanagawa and lives and practices in Tokyo.

Karl Johansson was a Latvian-Soviet avant-garde artist.