Related Research Articles

In Norse mythology, Gylfi, Gylfe, Gylvi, or Gylve was the earliest recorded king of Sviþjoð, Sweden, in Scandinavia. He is known by the name Gangleri when appearing in disguise. The Danish tradition on Gylfi deal with how he was tricked by Gefjon and her sons from Jötunheim, who were able to shapeshift into tremendous oxen.

The Ynglings were a dynasty of kings, first in Sweden and later in Norway, primarily attested through the poem Ynglingatal. The dynasty also appears as Scylfings in Beowulf. When Beowulf and Ynglingatal were composed sometime in the eighth to tenth centuries, the respective scop and skald (poet) expected his audience to have a great deal of background information about these kings, which is shown in the allusiveness of the references.

Kvenland, known as Cwenland, Qwenland, Kænland, and similar terms in medieval sources, is an ancient name for an area in Fennoscandia and Scandinavia. Kvenland, in that or nearly that spelling, is known from an Old English account written in the 9th century, which used information provided by Norwegian adventurer and traveler Ohthere, and from Nordic sources, primarily Icelandic. A possible additional source was written in the modern-day area of Norway. All known Nordic sources date from the 12th and 13th centuries. Other possible references to Kvenland by other names and spellings are also discussed here.

Nór is according to the Orkneyinga Saga the eponymous founder of Norway.

Randvér or Randver was a legendary Danish king. In Nordic legends, according to Sögubrot and the Lay of Hyndla, he was the son of Ráðbarðr the king of Garðaríki and Auðr the Deep-Minded, the daughter of the Danish-Swedish ruler Ivar Vidfamne. In these two sources, Auðr had Randver's brother, Harald Wartooth, in a previous marriage.

Halfdan the Valiant was a legendary Scanian prince, who was the father of Ivar Vidfamne according to Hervarar saga, the Ynglinga saga, Njal's Saga and Hversu Noregr byggdist. The genealogical work Hversu Noregr byggdist gives his father as Harald the Old, his grandfather as Valdar and his great-grandfather as Hróarr.

Fornjót is a jötunn in Norse mythology, and the father of Hlér ('sea'), Logi ('fire') and Kári ('wind'). It is also the name of a legendary king of "Finland and Kvenland". The principal study of this figure is by Margaret Clunies Ross.

Logi or Hálogi is a jötunn and the personification of fire in Norse mythology. He is a son of the jötunn Fornjótr and the brother of Ægir or Hlér ('sea') and Kári ('wind'). Logi married fire giantess Glöð and she gave birth to their two beautiful daughters—Eisa and Eimyrja.

In Norse mythology, Snær is seemingly a personification of snow, appearing in extant text as an euhemerized legendary Scandinavian king.

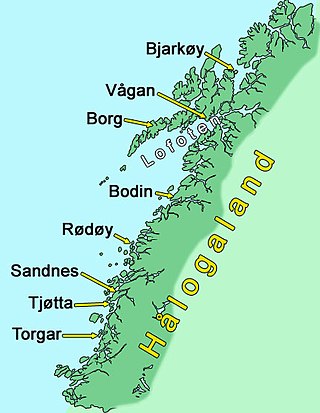

Hålogaland was the northernmost of the Norwegian provinces in the medieval Norse sagas. In the early Viking Age, before Harald Fairhair, Hålogaland was a kingdom extending between the Namdalen valley in Trøndelag county and the Lyngen fjord in Troms county.

Faravid was a legendary King of Kvenland who is mentioned in the Icelandic Egils saga from the early 13th century. According to the saga, Faravid made an alliance with the Norwegian Thorolf Kveldulfsson to fight against Karelian invaders.

The dog king is a Scandinavian tradition which appears in several Scandinavian sources: Chronicon Lethrense, Annals of Lund, Gesta Danorum, Heimskringla, Hversu Noregr byggðist and probably also in Skáldatal.

The origin of the name Kven is unclear. The name appears for the first time in a 9th-century Old English version, written by King Alfred of Wessex, of a work by the Roman author Orosius, in the plural form Cwenas.

The Kven Sea is mentioned as the northern border for the ancient Germania in The Old English Orosius, the history of the world published in England in 890 CE with a commission from King Alfred the Great himself.

The Dagling or Dögling dynasty was a legendary clan of the petty kingdom Ringerike in what today is Norway. It was descended from a Dag the Great.

Guðröðr was a legendary Scanian king who, according to the Ynglinga saga, was the brother of Halfdan the Valiant, Ivar Vidfamne's father. He is only known from late Icelandic sources dating from the 13th century.

There are scattered descriptions of early Finnish wars, conflicts involving the Finnish people, some of which took place before the Middle Ages. The earliest historical accounts of conflicts involving Finnish tribes, such as Tavastians, Karelians, Finns proper and Kvens, have survived in Icelandic sagas and in German, Norwegian, Danish and Russian chronicles as well as in Swedish legends and in Birch bark manuscripts. The most important sources are Novgorod First Chronicle, Primary Chronicle and Eric Chronicles.

Þorrablót is an Icelandic midwinter festival, named for the month of Þorri of the historical Icelandic calendar, and blót, literally meaning sacrifice.

Þorri is the Icelandic name of the personification of frost or winter in Norse mythology, and also the name of the fourth winter month in the Icelandic calendar.

Ringerike is a traditional district in Norway, commonly consisting of the municipalities Hole and Ringerike in Buskerud county. In older times, Ringerike had a larger range which went westward to the municipalities Krødsherad, Modum, and Sigdal, also in Buskerud.

References

- ↑ Egil's Saga, Chapter XIV

- ↑ Hversu Noregr byggðist at Sacred Texts.com.

- ↑ Dasent, George W., ed. (2014). "Part 1". The Orkneyinger's Saga. Netlancers Inc.

- ↑ Sturluson, Snorri (1912). "Frá Vanlanda [Of Vanlande]". In Jónsson, Finnur (ed.). Ynglingasaga (in Danish and Old Norse). Copenhagen: G.E.C. Gads Forlag. p. 20.

Hann þá vetrvist á Finnlandi með Snjá inum gamla ok fekk þar dóttur hans, Drífu. [He once stayed in Finland with Snær the Old and there he got his daughter, Drífu.]

- ↑ "16. Of Vanlande, Swegde's Son". Heimskringla: The Ynglinga Saga. Retrieved 21 April 2014– via The Medieval and Classical Literature Library.

- 1 2 Julku, Kyösti: Kvenland - Kainuunmaa. With English summary: The Ancient territory of Kainuu. Oulu, 1986.

- ↑ Hoops, Johannes (2001). Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde [Encyclopedia of Germanic Archaeology] (in German). Vol. 17. Walter de Gruyter. p. 515. ISBN 9783110169072.

Neben märchenhaften Sagen des 14. Jh.s. erwähnen noch einige norw. Qu. des 13./14. Jh.s. die Kwänen, etwa ihren verheerenden Kriegszug gegen Hálogaland im J. 1271 (5); dann verschwinden sie aus der geschichtl. Überlieferung. [Apart from 14th-century fairy-tale sagas also some Norwegian accounts from the 13th/14th century mention the Kvens, notably their devastating campaign against Hálogaland in the year 1271 (5); then they vanish from the chronicles.]

Citing Grotenfeld, K. (1909). "Über die alten Kvänen und Kvänland" [On the Old Kvens and Kvenland]. Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae (in German). I (1). - ↑ Lars Ivar Hansen and Bjørnar Olsen, Hunters in Transition: An Outline of Early Sámi History , Northern World 63, Leiden: Brill, 2014, ISBN 9789004252547, p. 152.

- ↑ Irmeli Valtonen, "An Interpretation of the Description of Northernmost Europe in the Old English Orosius", MA Thesis, University of Oulu, 1988, pp. 119–20 (pdf).

- ↑ Jukka Jari Korpela, "'Nationen' und 'Stämme' im mittelalterlichen Osteuropa: ihre Bedeutung für die Konstituierung eines nationalen Bewusstseins im 19. Jahrhundert", in Wieser Enzyklopädie des europäischen Ostens, ed. Karl Kaser, Dagmar Gramshammer-Hohl, Jan M. Piskorski and Elisabeth Vogel, Volume 12, Klagenfurt: Wieser, 2002, pp. 696–761, p. 729, p. 34 Archived 2011-11-29 at the Wayback Machine referencing Kyösti Julku: "So hat beispielsweise der Historiker Kyösti Julku den Großraumbegriff in der skizzierten Weise in Zusammenhang mit den Kvenen/Kajanen gebraucht,..." [E.g. historian Kyösti Julku used the term of the greater area in connection with the Kvens/Kajanians,...] (in German)

- ↑ Korhonen, Olavi (12–14 February 1982). Håp - vad är det för en båt? Lingvistiska synpunkter[Oops, what kind of boat is this? Linguistic points of view]. Bottnisk kontakt I. Föredrag vid maritimhistorisk konferens i Örnsköldsvik [Bothnian Contact I. Lectures at the Maritime History Conference at Örnsköldsvik] (in Swedish). Örnsköldsvik.

- ↑ Ulla Ehrensvärd, The History of the Nordic Map: From Myths to Reality, Helsinki: John Nurminen Foundation, 2006, ISBN 9789529745203, p. 130.

- ↑ Nils Chesnecopherus, Fulkommelige skäl och rättmätige orsaker, så och sanfärdige berättelser, hwarföre samptlige Sweriges rijkes ständer hafwe medh all fogh och rätt afsagdt Konung Sigismundum uthi Polen och storfurste i Littowen, etc. sampt alle hans efterkommande lijfs arfwingar ewärdeligen ifrå Sweriges rijkes crone och regemente, och all then hörsamheet och lydhno, som the honom efter arfföreeningen hafwe skyldige och plichtige warit, och uthi stadhen igen uthkorat, annammat och crönt then stormächtige, höghborne furste och herre, her Carl then nijonde, Sweriges, Göthes, Wendes, finnars, carelers, lappers i nordlanden, the caijaners och esters i Lifland, etc. Konung, sampt alle H. K. M.s efterkommande lijfs arfwingar, til theres och Sweriges rijkes rätte konung [The complete reasons and rightful causes, and likewise truthful accounts of how all of Sweden's Imperial States justifiably revoked King Sigismund of Poland and Great Prince of Lithuania, etc. and also eternally all of his consecutive heirs from the crown and reign of the Swedish realm, as well as all allegiance and obedience, which they owed him of heritage, and how the States again elected, accepted and crowned the mighty, noble prince and lord, Sir Charles IX, King of the Swedes, Goths, Wends, Finns, Karelians, Lapps in the Northlands, the Caijanians and Estonians in Livonia, etc.], Stockholm: Gutterwitz, 1607 OCLC 247275406.

- ↑ October 1607 example: "Titles of European hereditary rulers - Sweden". Archived from the original on 2009-10-22., citing Handlingar rörande Skandinaviens historia [Deeds concerning the history of Scandinavia]

- ↑ Julku, p. 102, also quotes the description of a Latin map by Bureus dated 1611: "Lapponiae, Bothniae, Cajaniaeque, Regni Sveciae Provinciarum Septentrionalium Nova Delineatio. Sculpta anno domini 1611." [A new outline of Lapland, Bothnia, and Caijania, the northern provinces of the kingdom of Sweden. Devised in 1611 A.D.] The map had been ordered by Charles IX. ("Kartta Bure teki Kaarle IX:n toimeksiannosta, lienee ollut esityö koko Pohjalan kartta varten." [This map made by Bureus on the order of Charles IX may have been the basis for a full map of the Northlands.])

- ↑ "Titles of European hereditary rulers - Sweden". Archived from the original on 2009-10-22.