Related Research Articles

An unlawful combatant, illegal combatant or unprivileged combatant/belligerent is a person who directly engages in armed conflict in violation of the laws of war and therefore is claimed not to be protected by the Geneva Conventions. The International Committee of the Red Cross points out that the terms "unlawful combatant", "illegal combatant" or "unprivileged combatant/belligerent" are not defined in any international agreements. While the concept of an unlawful combatant is included in the Third Geneva Convention, the phrase itself does not appear in the document. Article 4 of the Third Geneva Convention does describe categories under which a person may be entitled to prisoner of war status. There are other international treaties that deny lawful combatant status for mercenaries and children.

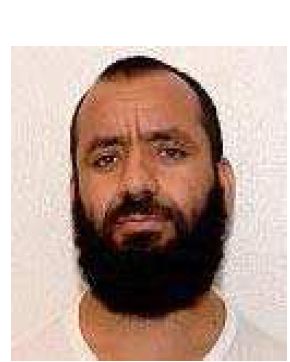

Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi is a Sudanese militant and paymaster for al-Qaeda. Qosi was held from January 2002 in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number is 54.

Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466 (2004), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Court held that foreign nationals held in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp could petition federal courts for writs of habeas corpus to review the legality of their detention. The Court's 6–3 judgment on June 28, 2004, reversed a D.C. Circuit decision which had held that the judiciary has no jurisdiction to hear any petitions from foreign nationals held in Guantanamo Bay.

Enemy combatant is a term for a person who, either lawfully or unlawfully, engages in hostilities for the other side in an armed conflict, used by the U.S. government and media during the War on Terror. Usually enemy combatants are members of the armed forces of the state with which another state is at war. In the case of a civil war or an insurrection "state" may be replaced by the more general term "party to the conflict".

The Combatant Status Review Tribunals (CSRT) were a set of tribunals for confirming whether detainees held by the United States at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp had been correctly designated as "enemy combatants". The CSRTs were established July 7, 2004 by order of U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz after U.S. Supreme Court rulings in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld and Rasul v. Bush and were coordinated through the Office for the Administrative Review of the Detention of Enemy Combatants.

Fouzi Khalid Abdullah Al Odah is a Kuwaiti citizen formerly held in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. He had been detained without charge in Guantanamo Bay since 2002. He was a plaintiff in the ongoing case, Al Odah v. United States, which challenged his detention, along with that of fellow detainees. The case was widely acknowledged to be one of the most significant to be heard by the Supreme Court in the current term. The US Department of Defense reports that he was born in 1977, in Kuwait City, Kuwait.

Extrajudicial prisoners of the United States, in the context of the early twenty-first century War on Terrorism, refers to foreign nationals the United States detains outside of the legal process required within United States legal jurisdiction. In this context, the U.S. government is maintaining torture centers, called black sites, operated by both known and secret intelligence agencies. Such black sites were later confirmed by reports from journalists, investigations, and from men who had been imprisoned and tortured there, and later released after being tortured until the CIA was comfortable they had done nothing wrong, and had nothing to hide.

Maasoum Abdah Mouhammad, a citizen of Syria, was formerly held in extrajudicial detention in the U.S. Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba.

Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel is a citizen of Yemen who was held in extrajudicial detention in the United States's Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internee Security Number was 043. The Department of Defense reports Moqbel was born on December 1, 1977, in Taiz, Yemen.

The Military Commissions Act of 2006, also known as HR-6166, was an Act of Congress signed by President George W. Bush on October 17, 2006. The Act's stated purpose was "to authorize trial by military commission for violations of the law of war, and for other purposes".

Moath Hamza Ahmed al-Alwi is a citizen of Yemen, held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. His detainee ID number is 28. Guantanamo analysts estimated he was born in 1977, in Al Hudaydah, Yemen.

Abdel Hamid Ibn Abdussalem Ibn Mifta Al Ghizzawi is a citizen of Libya who was held from June 2002 until March 2010 in the Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba because the United States classified him as an enemy combatant. His internment number was 654.

No-Hearing Hearings (2006) is the title of a study published by Professor Mark P. Denbeaux of the Center for Policy and Research at Seton Hall University School of Law, his son Joshua Denbeaux, and prepared under his supervision by research fellows at the center. It was released on October 17, 2006. It is one of a series of studies on the Guantanamo Bay detention center, the detainees, and government operations that the Center for Policy and Research has prepared based on Department of Defense data.

Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008), was a writ of habeas corpus petition made in a civilian court of the United States on behalf of Lakhdar Boumediene, a naturalized citizen of Bosnia and Herzegovina, held in military detention by the United States at the Guantanamo Bay detention camps in Cuba. The case underscored the essential role of habeas corpus as a safeguard against government overreach, ensuring that individuals cannot be detained indefinitely without the opportunity to challenge the legality of their detention. Guantánamo Bay is not formally part of the United States, and under the terms of the 1903 lease between the United States and Cuba, Cuba retained ultimate sovereignty over the territory, while the United States exercises complete jurisdiction and control. The case was consolidated with habeas petition Al Odah v. United States. It challenged the legality of Boumediene's detention at the United States Naval Station military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba as well as the constitutionality of the Military Commissions Act of 2006. Oral arguments on the combined cases were heard by the Supreme Court on December 5, 2007.

Al Odah v. United States is a court case filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights and co-counsels challenging the legality of the continued detention as enemy combatants of Guantanamo detainees. It was consolidated with Boumediene v. Bush (2008), which is the lead name of the decision.

In United States law, habeas corpus is a recourse challenging the reasons or conditions of a person's detention under color of law. The Guantanamo Bay detention camp is a United States military prison located within Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. A persistent standard of indefinite detention without trial and incidents of torture led the operations of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp to be challenged internationally as an affront to international human rights, and challenged domestically as a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth amendments of the United States Constitution, including the right of petition for habeas corpus. On 19 February 2002, Guantanamo detainees petitioned in federal court for a writ of habeas corpus to review the legality of their detention.

Bismullah v. Gates is a writ of habeas corpus appeal in the United States Justice System, on behalf of Bismullah —an Afghan detainee held by the United States in the Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. It was one of over 200 habeas corpus petitions filed on behalf of detainees held in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba.

Several captives released from extrajudicial detention in the Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba have filed a lawsuit against the USA for their detention -- Celikgogus v. Rumsfeld.

Tolfiq Nassar Ahmed Al Bihani is a citizen of Saudi Arabia held in the United States's Guantanamo Bay detention camps, in Cuba. His Guantanamo Internment Serial Number is 893.

Andrea J. Prasow is an American attorney and global human rights advocate. She leads The Freedom Initiative, a U.S.-based organization whose mission is "to bring international attention to the plight of political prisoners in the Middle East and advocate for their release." Prasow was appointed as The Freedom Initiative's executive director in November 2021.

References

- 1 2 3 "Guantanamo and the Semantics of Terror". Council on Hemispheric Affairs. July 14, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- 1 2 "Kristine Huskey: Practitioner in Residence, International Human Rights Clinic". University of Washington College of Law. Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ↑ "Working Women: Kristine Huskey". WJLA. July 6, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ Jennifer Senior (December 2006). "Gitmo's Girl". Marie Claire . Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ↑ Kristine A Huskey (Fall 2007). "Standards and Procedures for Classifying "Enemy Combatants": Congress, What Have You Done?". Texas International Law Journal. Archived from the original on 2008-04-13. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

When I began down this road five years ago, Guantánamo was literally a "legal black hole."1 The Supreme Court changed much of that in June 2004 when it ruled in my case, Al Odah v. United States, joined with Rasul v. Bush,2 that the detainees were entitled to bring habeas corpus petitions in federal court to challenge their detention. But after two years of fighting with the government over the meaning of Rasul, Congress abruptly passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006 ("MCA"),3 which ostensibly strips the Guantánamo detainees of the right to challenge any aspect of their detention, including the right to habeas corpus. Remarkably, we are almost exactly where we were five years ago, except that now, Congress has weighed in and approved of Guantánamo as a virtual law-free zone.

- 1 2 "Reading the North". Anchorage Daily News . 2009-06-27. Archived from the original on 2009-07-01. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ "Working Women: Kristine Huskey". WJLA. July 6, 2007. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

- ↑ "Women in International Law Networking Breakfast". American Society of International Law. 2009-07-09. Archived from the original on 2010-03-10.

- ↑ "UT Law welcomes detainee law expert Kristine Huskey". University of Texas. September 26, 2007. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ "Defending Habeas". University of Texas. Fall 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ "Kristine A Huskey: Clinical Professor, Director". University of Texas. Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ "UT Law launches National Security and Human Rights Clinic". University of Texas. September 4, 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ "Clinical Education at UT Law: Contact Us". University of Texas . Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ "Kristine A. Huskey, College of Law Profile". University of Arizona . Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ↑ Kristine A. Huskey, Aleigh Acerni (2009). My own Counsel: One Woman's Odyssey and Her Crusade for Justice at Guantanamo. The Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-59921-468-9.

- ↑ Huskey, Kristine A., A Strategic Imperative: Legal Representation of Unprivileged Enemy Belligerents in Status Determination Proceedings (December 1, 2012). 11 Santa Clara Journal of International Law 195 (2012). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2190144

- ↑ Huskey, Kristine A (2011). "Guantanamo and Beyond: Reflections on the Past, Present, and Future of Preventive Detention". University of New Hampshire Law Review. 9: 183. SSRN 2092091.

- ↑ Huskey, Kristine A.; Xenakis, Stephen N. (2009). "Hunger Strikes: Challenges to the Guantanamo Detainee Health Care Policy". Whittier Law Review. 30 (783). SSRN 2092086.

- ↑ Huskey, Kristine A (2010). "The American Way: Private Military Contractors & US Law after 9/11". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2184090. S2CID 153277062.

- ↑ Huskey, Kristine A (2007). "Standards and Procedures for Classifying 'Enemy Combatants': Congress, What Have You Done?". Texas International Law Journal. 43: 41. SSRN 2092076.