The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in what is now northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 201 BC one of the terms of the peace treaty prohibited Carthage from waging war without Rome's permission. Rome's ally, King Masinissa of Numidia, exploited this to repeatedly raid and seize Carthaginian territory with impunity. In 149 BC Carthage sent an army, under Hasdrubal, against Masinissa, the treaty notwithstanding. The campaign ended in disaster as the Battle of Oroscopa ended with a Carthaginian defeat and the surrender of the Carthaginian army. Anti-Carthaginian factions in Rome used the illicit military action as a pretext to prepare a punitive expedition.

The siege of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War fought between Carthage and Rome. It consisted of the nearly-three-year siege of the Carthaginian capital, Carthage. In 149 BC, a large Roman army landed at Utica in North Africa. The Carthaginians hoped to appease the Romans, but despite the Carthaginians surrendering all of their weapons, the Romans pressed on to besiege the city of Carthage. The Roman campaign suffered repeated setbacks through 149 BC, only alleviated by Scipio Aemilianus, a middle-ranking officer, distinguishing himself several times. A new Roman commander took over in 148 BC, and fared equally badly. At the annual election of Roman magistrates in early 147 BC, the public support for Scipio was so great that the usual age restrictions were lifted to allow him to be appointed commander in Africa.

The Tunisian Sahel or more precisely the Central East Tunisia is an area of central eastern Tunisia and one of the six Tunisian regions. It stretches along the eastern shore, from Hammamet in the north to Mahdia in the south, including the governorates of Monastir, Mahdia, Sfax and Sousse. Its name derives from the Arabic word sāḥil (ساحل), meaning "shore" or "coast". The region's economy is based especially on tourism and it contains the second-biggest airport in Tunisia: Monastir Habib Bourguiba International Airport.

Utica was an ancient Phoenician and Carthaginian city located near the outflow of the Medjerda River into the Mediterranean, between Carthage in the south and Hippo Diarrhytus in the north. It is traditionally considered to be the first colony to have been founded by the Phoenicians in North Africa. After Carthage's loss to Rome in the Punic Wars, Utica was an important Roman colony for seven centuries.

Maktar or Makthar, also known by other names during antiquity, is a town and archaeological site in Siliana Governorate, Tunisia.

La Marsa is a coastal city located in the northeastern part of Tunisia, situated along the Mediterranean Sea. It is part of the Tunis Governorate and has a population of around 100,000 people. The city is known for its beaches, upscale residential areas, and lively atmosphere, with numerous restaurants, cafes, and shops. It is connected to Tunis by the TGM railway. Gammarth is adjacent to El Marsa further up the coast.

The Punic religion, Carthaginian religion, or Western Phoenician religion in the western Mediterranean was a direct continuation of the Phoenician variety of the polytheistic ancient Canaanite religion. However, significant local differences developed over the centuries following the foundation of Carthage and other Punic communities elsewhere in North Africa, southern Spain, Sardinia, western Sicily, and Malta from the ninth century BC onward. After the conquest of these regions by the Roman Republic in the third and second centuries BC, Punic religious practices continued, surviving until the fourth century AD in some cases. As with most cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, Punic religion suffused their society and there was no stark distinction between religious and secular spheres. Sources on Punic religion are poor. There are no surviving literary sources and Punic religion is primarily reconstructed from inscriptions and archaeological evidence. An important sacred space in Punic religion appears to have been the large open air sanctuaries known as tophets in modern scholarship, in which urns containing the cremated bones of infants and animals were buried. There is a long-running scholarly debate about whether child sacrifice occurred at these locations, as suggested by Greco-Roman and biblical sources.

Althiburos was an ancient Berber, Carthaginian, and Roman settlement in what is now the Dahmani Delegation of the Kef Governorate of Tunisia. During the reign of emperor Hadrian, it became a municipality with Italian rights. It was the seat of a Christian bishop from the 4th to 7th centuries. The settlement was destroyed during the Muslim invasions and the area's population center moved to Ebba Ksour on the plain. This left Althiburos's ruins largely intact; they were rediscovered by travelers in the 18th century.

The Bardo National Museum is a museum of Tunis, Tunisia, located in the suburbs of Le Bardo.

Carthage National Museum is a national museum in Byrsa, Tunisia. Along with the Bardo National Museum, it is one of the two main local archaeological museums in the region. The edifice sits atop Byrsa Hill, in the heart of the city of Carthage. Founded in 1875 as the "Musée Saint-Louis" within the Chapelle Saint-Louis de Carthage in order to house the finds from the excavations of Alfred Louis Delattre, it contains many archaeological items from the Punic era and other periods.

Ksour Essef or Ksour Essaf is a town and commune in the Mahdia Governorate, Tunisia, on the coast of the Sahel, about 200 km south of Tunis. As of 2014 it had a population of 36,274.

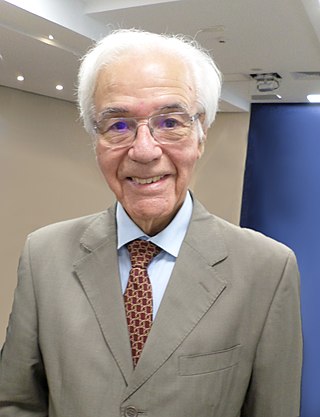

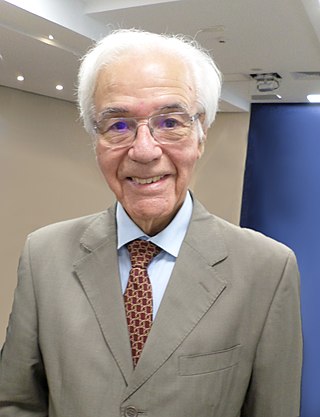

M'hamed Hassine Fantar is a professor of Ancient History of Archeology and History of Religion at Tunis University.

The Libyco-Punic Mausoleum of Dougga is an ancient mausoleum located in Dougga, Tunisia. It is one of three examples of the royal architecture of Numidia, which is in a good state of preservation and dates to the second century BC. It was restored by the government of French Tunisia between 1908 and 1910.

The Carthage Administration Inscription is an inscription in the Punic language, using the Phoenician alphabet, discovered on the archaeological site of Carthage in the 1960s and preserved in the National Museum of Carthage. It is known as KAI 303.

The Carthage Punic Ports were the old ports of the city of Carthage that were in operation during ancient times. Carthage was first and foremost a thalassocracy, that is, a power that was referred to as an Empire of the Seas, whose primary force was based on the scale of its trade. The Carthaginians, however, were not the only ones to follow that policy of control over the seas, since several of the people in those times "lived by and for the sea".

The Marsala Punic shipwreck is a third-century-BC shipwreck of two Punic ships. The wreck was discovered in 1969, off the shore of Isola Lunga, not far from Marsala on the western coast of Sicily. It was excavated from 1971 onwards. The excavation, led by Honor Frost and her team, lasted four years and revealed a substantial portion of the hull structure.

The Carthage tophet, is an ancient sacred area dedicated to the Phoenician deities Tanit and Baal, located in the Carthaginian district of Salammbô, Tunisia, near the Punic ports. This tophet, a "hybrid of sanctuary and necropolis", contains a large number of children's tombs which, according to some interpretations, were sacrificed or buried here after their untimely death. The area is part of the Carthage archaeological site, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Makthar Museum is a small Tunisian museum, inaugurated in 1967, located on the Makthar archaeological site, the ancient Mactaris. Initially a simple site museum using a building constructed to serve as a café on the site of a marabout, it comprises three rooms, some of which are displayed outside in a lapidary garden. Additionally, just behind the museum are the remains of a basilica.

The Makthar Archaeological Site, the remains of ancient Mactaris, is an archaeological site in west-central Tunisia, located in Makthar, a town on the northern edge of the Tunisian Ridge.

The Sanctuary of Thinissut is an archaeological site located in Tunisia, whose excavation started in the early 20th century. It is situated in the present-day locality of Bir Bouregba in the Cap Bon region, approximately five kilometers from the town of Hammamet and sixty kilometers southeast of the capital, Tunis.