Kwakwaka'wakw music is a sacred and ancient art of the Kwakwaka'wakw peoples that has been practiced for thousands of years. The Kwakwaka'wakw are a collective of twenty-five nations [1] :12-13 of the Wakashan language family who altogether form part of a larger identity comprising the Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, located in what is known today as British Columbia, Canada.

Something that is sacred is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity or considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspiring awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects, or places.

A nation is a stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, history, ethnicity, or psychological make-up manifested in a common culture. A nation is distinct from a people, and is more abstract, and more overtly political, than an ethnic group. It is a cultural-political community that has become conscious of its autonomy, unity, and particular interests.

Contents

- Kwakwaka'wakw dancing societies

- Hamatsa ("hā`mats'a")

- Winalagilis

- Atlakim

- Dluwalakha

- Kwakwaka'wakw ensemble

- Whistle

- Drum ("mEnā'tsē")

- Rattle ("ia'tEn")

- Clapper

- References

The Kwakwaka'wakw peoples use instruments in conjunction with dance and song for the purposes of ceremony, ritual, and storytelling (see also Kwakwaka'wakw mythology). [2] :94 Certain Kwakwaka'wakw traditions include ghosts who are able to bring back the dead with their song. [3] :320-321 Love songs are also an important part of Kwakwaka'wakw music. [1] :45 [3]

A musical instrument is an instrument created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. The history of musical instruments dates to the beginnings of human culture. Early musical instruments may have been used for ritual, such as a trumpet to signal success on the hunt, or a drum in a religious ceremony. Cultures eventually developed composition and performance of melodies for entertainment. Musical instruments evolved in step with changing applications.

Dance is a performing art form consisting of purposefully selected sequences of human movement. This movement has aesthetic and symbolic value, and is acknowledged as dance by performers and observers within a particular culture. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoire of movements, or by its historical period or place of origin.

A song is a single work of music that is typically intended to be sung by the human voice with distinct and fixed pitches and patterns using sound and silence and a variety of forms that often include the repetition of sections. Through semantic widening, a broader sense of the word "song" may refer to instrumentals.

A mixture of percussive instrumentation, especially log and stick, and box or hide drums, as well as rattles, whistles, and the clapper (musical instrument) create a beat while vocal expression establishes the rhythm. Instrument makers specifically design new musical instruments for each respective dance. [2] :94

A percussion instrument is a musical instrument that is sounded by being struck or scraped by a beater ; struck, scraped or rubbed by hand; or struck against another similar instrument. The percussion family is believed to include the oldest musical instruments, following the human voice.

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic material, a natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin that resists compression. Wood is sometimes defined as only the secondary xylem in the stems of trees, or it is defined more broadly to include the same type of tissue elsewhere such as in the roots of trees or shrubs. In a living tree it performs a support function, enabling woody plants to grow large or to stand up by themselves. It also conveys water and nutrients between the leaves, other growing tissues, and the roots. Wood may also refer to other plant materials with comparable properties, and to material engineered from wood, or wood chips or fiber.

A rattle is a type of percussion instrument which produces a sound when shaken. Rattles are described in the Hornbostel–Sachs system as Shaken Idiophones or Rattles (112.1).

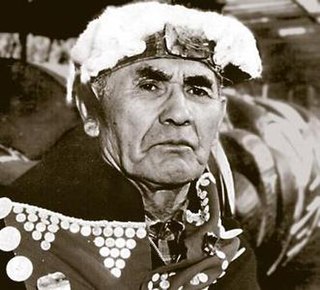

The Kwak'wala word for "summer song" is baquyala, and the word for "winter song" is ts’ē⁾k·ala. [4] :75 The arrival of the next winter season is celebrated each year in a four-day festival of song and dance called tsetseqa, or Winter Ceremonial. [5] :101-102Tsetseqa begins with singing the songs of those who died since the last winter season. [2] :103 The entire tsetseqa season is devoted to ceremony, including initiation of the young into various dancing societies. [2] :36

Summer is the hottest of the four temperate seasons, falling after spring and before autumn. At the summer solstice, the days are longest and the nights are shortest, with day length decreasing as the season progresses after the solstice. The date of the beginning of summer varies according to climate, tradition, and culture. When it is summer in the Northern Hemisphere, it is winter in the Southern Hemisphere, and vice versa.

Winter is the coldest season of the year in polar and temperate zones. It occurs after autumn and before spring in each year. Winter is caused by the axis of the Earth in that hemisphere being oriented away from the Sun. Different cultures define different dates as the start of winter, and some use a definition based on weather. When it is winter in the Northern Hemisphere, it is summer in the Southern Hemisphere, and vice versa. In many regions, winter is associated with snow and freezing temperatures. The moment of winter solstice is when the Sun's elevation with respect to the North or South Pole is at its most negative value. The day on which this occurs has the shortest day and the longest night, with day length increasing and night length decreasing as the season progresses after the solstice. The earliest sunset and latest sunrise dates outside the polar regions differ from the date of the winter solstice, however, and these depend on latitude, due to the variation in the solar day throughout the year caused by the Earth's elliptical orbit.

Another very important festival involving song and dance is the potlatch (Chinook: "to give"), [1] :16 a Kwakwaka'wakw tradition of sharing wealth and prestige in order to establish status and ensure witnesses remember the respective stories celebrated. [2] :33-34 Potlatches often occur during tsetseqa to announce a new initiate into one of the secret dancing societies. [1] :23-24

A potlatch is a gift-giving feast practiced by Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States, among whom it is traditionally the primary economic system. This includes the Heiltsuk, Haida, Nuxalk, Tlingit, Makah, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Coast Salish cultures. Potlatches are also a common feature of the peoples of the Interior and of the Subarctic adjoining the Northwest Coast, though mostly without the elaborate ritual and gift-giving economy of the coastal peoples.

Chinookan peoples include several groups of indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest in the United States who speak the Chinookan languages. In the early 19th century, the Chinookan-speaking peoples resided along the Lower and Middle Columbia River (Wimahl) from the river's gorge downstream to the river's mouth, and along adjacent portions of the coasts, from Tillamook Bay of present-day Oregon in the south, north to Willapa Bay in southwest Washington. In 1805 the Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered the Chinook tribe on the lower Columbia. The name ″Chinook″ came from a Chehalis word Tsinúk for the inhabitants of and a particular village site on Baker Bay.

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating old English word weal, which is from an Indo-European word stem. A community, region or country that possesses an abundance of such possessions or resources to the benefit of the common good is known as wealthy.