Ahmed I was sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1603 to his death. Ahmed's reign is noteworthy for marking the first breach in the Ottoman tradition of royal fratricide; henceforth, Ottoman rulers would no longer systematically execute their brothers upon accession to the throne. He is also well known for his construction of the Blue Mosque, one of the most famous mosques in Turkey.

Murad III was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Safavids. The long-independent Morocco was at a time made a vassal of the empire but they would regain independence in 1582. His reign also saw the empire's expanding influence on the eastern coast of Africa. However, the empire would be beset by increasing corruption and inflation from the New World which led to unrest among the Janissary and commoners. Relations with Elizabethan England were cemented during his reign as both had a common enemy in the Spanish. He was a great patron in the arts where he commissioned the Siyer-i-Nebi and other illustrated manuscripts.

Selim II, also known as Selim the Blond or Selim the Drunk, was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1566 until his death in 1574. He was a son of Suleiman the Magnificent and his wife Hurrem Sultan. Selim had been an unlikely candidate for the throne until his brother Mehmed died of smallpox, his half-brother Mustafa was strangled to death by the order of his father, his brother Cihangir succumbed to chronic health issues, and his brother Bayezid was killed on the order of his father after a rebellion against Selim. Selim died on 15 December 1574 and was buried in Hagia Sophia.

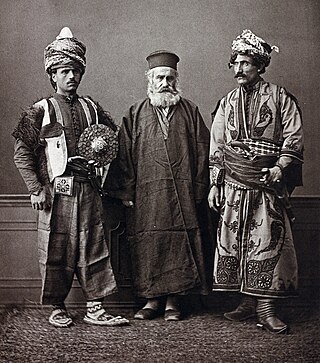

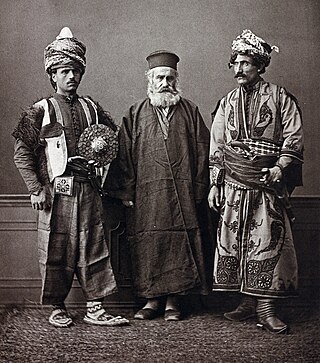

Pascal Sébah (1823–1886) was a photographer in Constantinople and Cairo, who produced a prolific number of images of Egypt, Turkey, and Greece to serve the tourist trade.

The military of the Ottoman Empire was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman Empire used various flags and naval ensigns during its history. The star and crescent came into use in the second half of the 18th century. A buyruldu (decree) from 1793 required that the ships of the Ottoman Navy were to use a red flag with the star and crescent in white. In 1844, a version of this flag, with a five-pointed star, was officially adopted as the Ottoman national flag. The decision to adopt a national flag was part of the Tanzimat reforms which aimed to modernize the Ottoman state in line with the laws and norms of contemporary European states and institutions.

The siege of Szigetvár or the Battle of Szigeth was a siege of the fortress of Szigetvár, Kingdom of Hungary, that blocked Sultan Suleiman's line of advance towards Vienna in 1566. The battle was fought between the defending forces of the Habsburg monarchy under the leadership of Nikola IV Zrinski, former Ban of Croatia, and the invading Ottoman army under the nominal command of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

The Battle of Sisak was fought on 22 June 1593 between Ottoman Bosnian forces and a combined Christian army from the Habsburg lands, mainly Kingdom of Croatia and Inner Austria. The battle took place at Sisak, central Croatia, at the confluence of the Sava and Kupa rivers, on the borderland between Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

The Battle of Zenta, also known as the Battle of Senta, was fought on 11 September 1697, near Zenta, Kingdom of Hungary, between Ottoman and Holy League armies during the Great Turkish War. The battle was the most decisive engagement of the war, and it saw the Ottomans suffer an overwhelming defeat by an Imperial force half as large sent by Emperor Leopold I.

Antoine Ignace Melling was a painter, architect and voyager who is counted among the “Levantine Artists”. He is famous for his vedute of Constantinople, a town where he lived for 18 years. He was imperial architect to Sultan Selim III and Hatice Sultan and later landscape painter to the Empress Josephine of France. His most influential work is published as Voyage pittoresque de Constantinople et des rives du Bosphore.

The Ottoman–Habsburg wars were fought from the 16th through the 18th centuries between the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy, which was at times supported by the Kingdom of Hungary, Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and Habsburg Spain. The wars were dominated by land campaigns in Hungary, including Transylvania and Vojvodina, Croatia, and central Serbia.

The Column of Arcadius was a Roman triumphal column in the forum of Arcadius in Constantinople built in the early 5th century AD. The marble column was historiated with a spiralling frieze of reliefs on its shaft and supported a colossal statue of the emperor, probably made of bronze, which fell down in 740. Its summit was accessible by an internal spiral staircase. Only its massive masonry base survives.

The Franco-Ottoman Alliance, also known as the Franco-Turkish Alliance, was an alliance established in 1536 between the King of France Francis I and the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Suleiman I. The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance was one of the longest-lasting and most important foreign alliances of France, and was particularly influential during the Italian Wars. The Franco-Ottoman military alliance reached its peak around 1553 during the reign Henry II of France.

The territorial evolution of the Ottoman Empire spans seven centuries. The Ottoman Empire at its extent, for a shorter period of time, reached 19.9 million km², but soon declined to 13.4 million km².

Nicolas de Nicolay, Sieur d'Arfeville & de Belair, (1517–1583) of the Nicolay (family) was a French geographer.

Melchior Lorck was a renaissance painter, draughtsman, and printmaker of Danish-German origin. He produced the most thorough visual record of the life and customs of Turkey in the 16th century, to this day a unique source. He was also the first Danish artist of whom a substantial biography is reconstructable and a substantial body of artworks is attributable.

The capture of Cairo was the capture of the capital of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt by the Ottoman Empire in 1517.

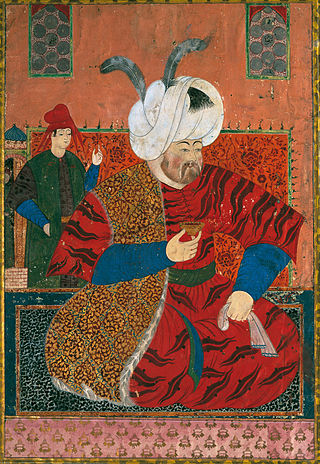

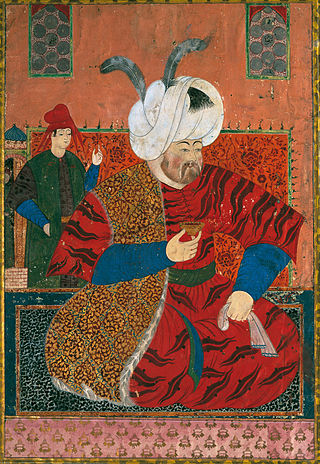

The Book of Felicity is an illuminated manuscript made in the Ottoman Empire in 1582. Commissioned by Sultan Murad III, who ruled the empire from 1574 to 1595, its text was translated from Arabic and all its miniatures were apparently directed by the famous master Nakkaş Osman, who undoubtedly painted the opening series of images related to the signs of the zodiac. Osman, the head of the painters at the seraglio workshop from 1570 onwards, created a style renowned for its lifelike portraits that influenced other artists in Murad's court.

David Ungnad von Sonnegg was the Holy Roman Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1572 to 1578. He was sent by Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor and accredited by Sultan Selim II.

Lambert Wyts or Lambert Wijts was a Flemish courtier, draughtsman and diarist. Born into a prominent family in the County of Flanders he became a courtier in the service of the Habsburg dynasty. In this role, he made three diplomatic trips respectively to Spain, Turkey and the Holy Roman Empire. He kept a diary of his travels which contribute to the understanding of contemporary circumstances in those countries. In particular, his diary regarding his trip to Turkey, with its drawings of events and local people and their dress, is of importance in this regard. In the past he has been mixed up with a contemporary Fleming from Mechelen by the name Lambert de Vos, a trained artist who traveled at the same time to Turkey where he made various drawings of local costumes and sights.