Laptots were African colonial troops in the service of France between 1750 and the early 1900s.

Laptots were African colonial troops in the service of France between 1750 and the early 1900s.

The term laptot probably derives from the word lappato bi in the Wolof language, referring to interpreters, intermediaries or brokers. [1] Most laptots were recruited in Senegal, especially at French outposts in Saint-Louis and Dakar, during the late 18th and 19th centuries. Laptots were closely linked with the Tirailleurs sénégalais , a military unit which enlisted soldiers from France's colonies in West Africa, founded in 1857. Unlike the tirailleurs, however, laptots served exclusively in Africa and Madagascar. [2]

The French navy hired laptots on a temporary basis, using them to guard outposts, serve aboard French naval and commercial vessels, and perform various other tasks throughout French possessions in Africa. Laptots typically signed up for two-year contracts. They were often more reliable and effective than European personnel, who were too susceptible to endemic diseases such as malaria. Many laptots joined on a voluntary basis, although others were slaves in local communities who were forced to hand over half their wages to their owners. According to historian Francois Manchuelle, pay for some laptots—particularly those who served aboard navy boats on the Senegal River—was competitive with salaries for French sailors at the time. Manchuelle contends that men of the Soninke ethnic group were attracted to laptot service by the prospects of accumulating cash with which to compete for social status in their home communities. [3]

Laptots were essential not only to French administration of its West African possessions, but also to subsequent French exploration and colonial penetration of Central Africa, parts of which became French Equatorial Africa after 1910. When the Franco-Italian explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza first ventured into the Equatorial African interior in 1876, he was accompanied by 13 laptots and four local interpreters as well as three other Frenchmen. Brazza's second expedition, in 1880, also relied heavily on laptots to carry loads, deliver messages, and provide protection against hostile populations. One laptot on this expedition was Malamine Camara, who achieved some renown for his exploits while serving under Brazza's command in Congo. Camara and two other laptots manned France's first outpost on the banks of the Congo River from October 1880 until May 1882, on the future site of Brazzaville, and may have prevented France's newly acquired territory there from being taken over by Belgium. [4] Laptots provided the bulk of French manpower needs in its Equatorial African colonies until well into the 20th century, when more personnel began to be recruited locally. [5]

Brazzaville is the capital and largest city of the Republic of the Congo. Constituting the financial and administrative centre of the country, it is located on the north side of the Congo River, opposite Kinshasa, the capital city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

French Equatorial Africa, or the AEF, was the federation of French colonial possessions in Equatorial Africa, extending northwards from the Congo River into the Sahel, and comprising what are today the countries of Chad, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon.

The French colonial empire comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire", that existed until 1814, by which time most of it had been lost or sold, and the "Second French Colonial Empire", which began with the conquest of Algiers in 1830. At its apex between the two world wars, the second French colonial empire was the second-largest colonial empire in the world behind the British Empire.

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis, was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French expedition to Fashoda on the White Nile river sought to gain control of the Upper Nile river basin and thereby exclude Britain from the Sudan. The French party and a British-Egyptian force met on friendly terms, but back in Europe, it became a war scare. The British held firm as both empires stood on the verge of war with heated rhetoric on both sides. Under heavy pressure, the French withdrew, ensuring Anglo-Egyptian control over the area.

Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza, was an Italian-French explorer. With his family's financial help, he explored the Ogooué region of Central Africa, and later with the backing of the Société de Géographie de Paris, he reached far into the interior along the right bank of the Congo. He has often been depicted as a man of friendly manner, great charm and peaceful approach towards the Africans he met and worked with on his journeys, but recent research has revealed that he in fact alternated this kind of approach with more calculated deceit and at times relentless armed violence towards local populations. Under French colonial rule, the capital of the Republic of the Congo was named Brazzaville after him and the name was retained by the post-colonial rulers, one of the few African nations to do so.

The French Congo or Middle Congo was a French colony which at one time comprised the present-day area of the Republic of the Congo and parts of Gabon, and the Central African Republic. In 1910, it was made part of the larger French Equatorial Africa.

Émile Gentil was a French colonial administrator, naval officer, and military leader.

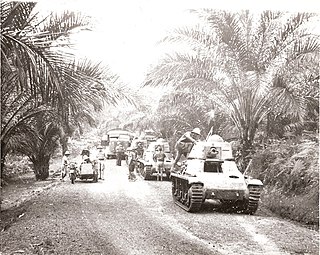

The Troupes coloniales or Armée coloniale, commonly called La Coloniale, were the military forces of the French colonial empire from 1900 until 1961. From 1822 to 1900 these troops were designated Troupes de marine, and in 1961 they readopted this name. They were recruited from mainland France or from the French settler and indigenous populations of the empire. This force played a substantial role in the conquest of the empire, in World War I, World War II, the First Indochina War and the Algerian War.

The Soninke people are a West African Mande-speaking ethnic group found in Mali, Fouta Djallon, southern Mauritania, eastern Senegal, Guinea and The Gambia. They speak the Soninke language, also called the Serakhulle or Azer language, which is one of the Mande languages. Soninke people were the founders of the ancient empire of Ghana or Wagadou c. 300–1240 CE, Subgroups of Soninke include the Maraka and Wangara. When the Ghana empire was destroyed, the resulting diaspora brought Soninkes to Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, Gambia, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinée-Conakry, modern-day Republic of Ghana, and Guinea-Bissau where some of this trading diaspora was called Wangara.

The Senegalese Tirailleurs were a corps of colonial infantry in the French Army. They were initially recruited from Senegal, French West Africa and subsequently throughout Western, Central and Eastern Africa: the main sub-Saharan regions of the French colonial empire. The noun tirailleur, which translates variously as 'skirmisher', 'rifleman', or 'sharpshooter', was a designation given by the French Army to indigenous infantry recruited in the various colonies and overseas possessions of the French Empire during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Battle of Gabon, also called the Gabon Campaign, occurred in November 1940 during World War II. The battle resulted in forces under the orders of General de Gaulle taking the colony of Gabon and its capital, Libreville, from Vichy France, and the rallying of French Equatorial Africa to Free France.

Malamine Camara was a Senegalese sergeant in the French colonial army, and a key figure in the extension of French colonial rule in the Congo Basin.

The Jakhanke -- also spelled Jahanka, Jahanke, Jahanque, Jahonque, Diakkanke, Diakhanga, Diakhango, Dyakanke, Diakhanké, Diakanké, or Diakhankesare -- are a Manding-speaking ethnic group in the Senegambia region, often classified as a subgroup of the larger Soninke. The Jakhanke have historically constituted a specialized caste of professional Muslim clerics (ulema) and educators. They are centered on one larger group in Guinea, with smaller populations in the eastern region of The Gambia, Senegal, and in Mali near the Guinean border. Although generally considered a branch of the Soninke, their language is closer to Western Manding languages such as Mandinka.

The French conquest of Senegal started in 1659 with the establishment of Saint-Louis, Senegal, followed by the French capture of the island of Gorée from the Dutch in 1677, but would only become a full-scale campaign in the 19th century.

Dr. Noël Eugène Ballay was a French auxiliary doctor of the French navy, and a poet. He was an explorer and colonial administrator, the second Governor-General of French West Africa.

Petit nègre, also known as Français tirailleur or Petinègue or Forofifon naspa, is a pidgin language that was spoken by West African soldiers and their white officers in the French colonial army approximately 1857–1954. It never creolized.

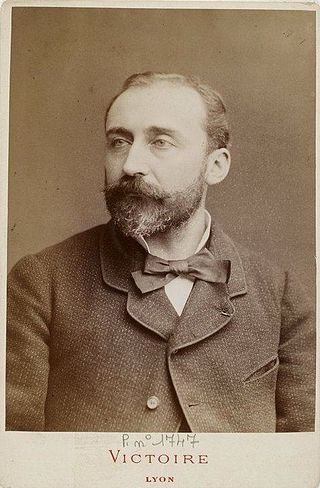

Fortuné Charles de Chavannes, born 19 May 1853 in Lyon and died 7 February 1940 in Antibes, was a French colonial administrator. He accompanied Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza on the Mission de l'Ouest africain from 1883 to 1886, and participated in the exploration and establishment of French Congo.

Louis Albert Grodet was a French civil servant, colonial administrator and politician. He trained as a lawyer, then worked his way up the ranks in the Ministry of Commerce and then the Colonial Ministry. He was governor in turn of Martinique, French Guiana, French Sudan, French Congo and French Guiana for a second term. Although forceful, he lacked leadership skills and had poor judgement. In the French Sudan he was unable to stop the army from ignoring government instructions and pursuing a costly expansionist policy. He tried but failed to suppress slavery, at a time when the local troops often expected a share of booty in the form of slaves. After retiring he was Deputy of French Guiana from 1910 to 1919.

Congolese nationality law is a legal statute regulated by the Constitution of the Republic of the Congo. It determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of the Republic of the Congo. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Congolese nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in the Republic of the Congo, or jus sanguinis, born abroad to parents with Congolese nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.

Gabonese nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Gabon, as amended; the Gabonese Nationality Code, and its revisions; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Gabon. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. Gabonese nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, i.e. by birth in Gabon, or of jus sanguinis, born to parents with Gabonese nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalization.