Related Research Articles

The Pitcairn Islands are a British Overseas Territory in the South Pacific Ocean, with a population of about 50. The politics of the islands takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic dependency, whereby the Mayor is the head of government. The territory's constitution is the Local Government Ordinance of 1964. In terms of population, the Pitcairn Islands is the smallest democracy in the world.

The history of Vanuatu spans over 3,200 years.

The politics of Vanuatu take place within the framework of a constitutional democracy. The constitution provides for a representative parliamentary system. The head of the Republic is an elected President. The Prime Minister of Vanuatu is the head of government.

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enforcement, prosecutions or even responsibility for legal affairs generally. In practice, the extent to which the attorney general personally provides legal advice to the government varies between jurisdictions, and even between individual office-holders within the same jurisdiction, often depending on the level and nature of the office-holder's prior legal experience.

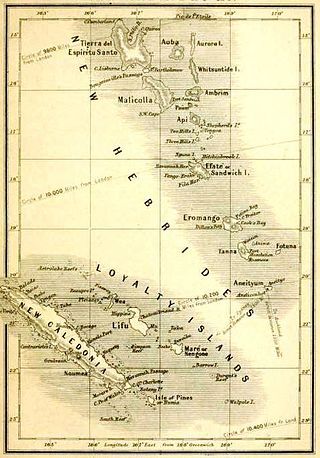

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group in the South Pacific Ocean that is now Vanuatu. Native people had inhabited the islands for three thousand years before the first Europeans arrived in 1606 from a Spanish expedition led by Portuguese navigator Pedro Fernandes de Queirós. The islands were named by Captain James Cook in 1774 and subsequently colonised by both the British and the French.

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the adversarial system, which is adopted in common law, or inquisitorial system, which is adopted in civil law. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the case in a criminal trial against the defendant, an individual accused of breaking the law. Typically, the prosecutor represents the state or the government in the case brought against the accused person.

The court system of Canada is made up of many courts differing in levels of legal superiority and separated by jurisdiction. In the courts, the judiciary interpret and apply the law of Canada. Some of the courts are federal in nature, while others are provincial or territorial.

The Supreme Court (Filipino: Kataas-taasang Hukuman; colloquially referred to as the Korte Suprema, is the highest court in the Philippines. The Supreme Court was established by the Second Philippine Commission on June 11, 1901 through the enactment of its Act No. 136, an Act which abolished the Real Audiencia de Manila, the predecessor of the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court of Singapore is a set of courts in Singapore, comprising the Court of Appeal and the High Court. It hears both civil and criminal matters. The Court of Appeal hears both civil and criminal appeals from the High Court. The Court of Appeal may also decide a point of law reserved for its decision by the High Court, as well as any point of law of public interest arising in the course of an appeal from a court subordinate to the High Court, which has been reserved by the High Court for decision of the Court of Appeal.

The judicial system of Turkey is defined by Articles 138 to 160 of the Constitution of Turkey.

The Court of Appeal of Singapore is the highest court in the judicial system of Singapore. It is the upper division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the lower being the High Court. The Court of Appeal consists of the chief justice, who is the president of the Court, and the judges of the Court of Appeal. The chief justice may ask judges of the High Court to sit as members of the Court of Appeal to hear particular cases. The seat of the Court of Appeal is the Supreme Court Building.

The legal system of South Korea is a civil law system that has its basis in the Constitution of the Republic of Korea. The Court Organization Act, which was passed into law on 26 September 1949, officially created a three-tiered, independent judicial system. The revised Constitution of 1987 codified judicial independence in Article 103, which states that, "Judges rule independently according to their conscience and in conformity with the Constitution and the law." The 1987 rewrite also established the Constitutional Court, the first time that South Korea had an active body for constitutional review.

The Judiciary of the Czech Republic is set out in the Constitution, which defines courts as independent institutions within the constitutional framework of checks and balances.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Vanuatu:

The Office of the Solicitor General of the Philippines, formerly known as the Bureau of Justice, is an independent and autonomous office attached to the Department of Justice. The OSG is headed by Menardo Guevarra.

The Supreme Court of Nauru was the highest court in the judicial system of the Republic of Nauru till the establishment of the Nauruan Court of Appeal in 2018.

The Supreme Court of Mauritius is the highest court of Mauritius and the final court of appeal in the Mauritian judicial system. It was established in its current form in 1850, replacing the Cour d'Appel established in 1808 during the French administration and has a permanent seat in Port Louis. There is a right of appeal from the Supreme Court of Mauritius directly to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the court of final appeal for Mauritius.

The judiciary of Solomon Islands is a branch of the Government of Solomon Islands that interprets and applies the laws of Solomon Islands, to ensure equal justice under law, and to provide a mechanism for dispute resolution. The legal system is derived from chapter VII, part II of the Constitution, adopted when the country became independent from the United Kingdom in 1978. The Constitution provided for the creation of a High Court, with original jurisdiction in civil and criminal cases, and a Court of Appeal. It also provided for the possibility of "subordinate courts", with no further specification (art.84).

The judiciary of Uruguay is a branch of the government of Uruguay that interprets and applies the laws of Uruguay, to ensure equal justice under law, and to provide a mechanism for dispute resolution. The legal system of Uruguay is a civil law system, with public law based on the 1967 Constitution, amended in 1989, 1994, 1997, and 2004. The Constitution declares Uruguay to be a democratic republic, and separates the government into three equal branches, executive, legislative and judicial. Private relationships are subject to the Uruguayan Civil Code, originally published in 1868. The Constitution defines the judiciary as a hierarchical system courts, with the highest court being a five-member Supreme Court, who are appointed by the legislative branch of the government, for ten-year terms. The Supreme Court appoints the judges of most of the lower courts. Below the Supreme Court, there are sixteen courts of appeal, each of which has three judges. Seven of the courts of appeal specialize in civil matters, four specialize in criminal matters, three cover labour law, and two focus on family matters. At the lowest tier are justices of the peace and courts of first instance specialized in administrative, civil, criminal, customs, juvenile, and labour cases. Although the hierarchy, all of them are functionally and structurally impartial, that is, the tribunal should not be interested in the object of the particular case, and the higher tribunal does not impose a behaviour nor precedent to the lower ones. There are also separate courts for auditing, elections and the military.

The law of Cyprus is a legal system which applies within the Republic of Cyprus. Although Cypriot law is extensively codified, it is still heavily based on English common law in the sense that the fundamental principle of precedent applies.

References

- ↑ William F.S. Miles, Bridging Mental Boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8248-2048-7, pp.15-16

- ↑ Miles, op.cit., pp.33-7

- 1 2 "Vanuatu - Sources of Law", Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute

- 1 2 3 Constitution of Vanuatu

- ↑ Constitution of Vanuatu Archived 2011-02-16 at the Wayback Machine , French language version

- ↑ Anthony Angelo, "L'application du droit français au Vanuatu", Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute

- ↑ "Pacific Media Centre | articles: VANUATU: Public Prosecutor considers libel action against assaulted publisher". Pacific Media Centre. Pacific Media Centre. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Beyond Case Law: Kastom and Courts in Vanuatu" Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine , Miranda Forsyth, University of French Polynesia

- ↑ Revised Laws of Vanuatu 1988

- ↑ Civil Procedure Code Archived 2011-02-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Criminal Procedure Code [ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Island Courts Act 1983, s.10

- ↑ "Vanuatu Courts System Information", Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute

- ↑ "Legal profession". Commonwealth Law Bulletin. 11: 183–199. January 1985. doi:10.1080/03050718.1985.9985794.

- ↑ "Office of the Public Solicitor" (PDF).

- ↑ Powles, Guy; Pulea, Mere (1988). Pacific Courts and Legal Systems. editorips@usp.ac.fj. ISBN 9789820200432.

- ↑ Forsyth, Miranda (2009-09-01). A Bird that Flies with Two Wings: Kastom and State Justice Systems in Vanuatu. ANU E Press. ISBN 9781921536793.

- ↑ "REPUBLIC OF VANUATU / BILL FOR THE PUBLIC SOLICITOR (AMENDMENT) ACT NO. OF 2016" (PDF).

- ↑ "Hon. Justice Saksak Abraham Oliver - Judiciary of the Republic of Vanuatu". courts.gov.vu. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ↑ Vanuatu law reports. 1996.

- ↑ LAMB, DAVID (1987-07-14). "Reporter's Notebook : Admiration for U.S. Fuels Offbeat Statehood Drive in New Caledonia". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035 . Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- ↑ "REPUBLIC OF VANUATU / COUNTRY REPORT 26th PACIFIC ISLANDS LAWOFFICERS NETWORK( PILON) (Rarotonga, Cook Islands 5– 1O December 2007)".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ REPUBLIC OF VANUATU / COUNTRY REPORT 28th PACIFIC ISLANDS LAW OFFICERS NETWORK MEETING (PILON) (Apia, Samoa, 12–16 December 2009)

- 1 2 "Induction Program for Members of the 9th National Parliament of the Republic of Vanuatu" (PDF). October 2008.

- ↑ "REPUBLIC OF VANUATU / COUNTRY REPORT30th PACIFIC ISLANDS LAW OFFICERS NETWORK (PILON) ANNUAL MEETING 4-6 December 2011, Auckland, New Zealand" (PDF).

- ↑ "EPUBLIC OF VANUATU / COUNTRY REPORT 31st PACIFIC ISLANDS LAW OFFICERS NETWORK MEETING (PILON) (Kokopo, Papua New Guinea, October 2012)" (PDF).

- ↑ "Public Solicitor's Office Vanuatu / LAWYER HANDBOOK 2015" (PDF).

- ↑ "Public Prosecutors Office". mjcs.gov.vu. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ↑ "SOLOMON ISLANDS GOVERNMENT QUESTIONNAIRE FOR THE AUSTRALIAN FEDERAL DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS, MR DAMIAN BUGG QC" (PDF).

- ↑ "Vanuatu public prosecutor Tavoa quits over alleged negligence". Radio New Zealand. 2014-01-30. Retrieved 2018-03-13.

- ↑ Vaudin d'Imecourt C.J., Banga v Waiwo, Supreme Court of Vanuatu, 1996

- ↑ "Beyond Case Law: Kastom and Courts in Vanuatu" Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine , Miranda Forsyth, University of French Polynesia

- ↑ Vaudin d'Imecourt C.J., Banga v Waiwo, op.cit.

- ↑ "Beyond Case Law: Kastom and Courts in Vanuatu" Archived 2012-03-05 at the Wayback Machine , Miranda Forsyth, University of French Polynesia

- ↑ Miranda Forsyth, A Bird that Flies with Two Wings: The kastom and state justice systems in Vanuatu , ch.5: "The relationship between the state and kastom systems", 2007