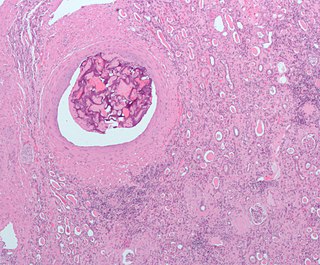

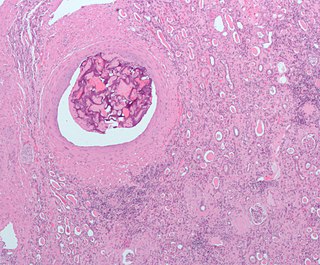

An embolism is the lodging of an embolus, a blockage-causing piece of material, inside a blood vessel. The embolus may be a blood clot (thrombus), a fat globule, a bubble of air or other gas, amniotic fluid, or foreign material. An embolism can cause partial or total blockage of blood flow in the affected vessel. Such a blockage may affect a part of the body distant from the origin of the embolus. An embolism in which the embolus is a piece of thrombus is called a thromboembolism.

Chest pain is pain or discomfort in the chest, typically the front of the chest. It may be described as sharp, dull, pressure, heaviness or squeezing. Associated symptoms may include pain in the shoulder, arm, upper abdomen, or jaw, along with nausea, sweating, or shortness of breath. It can be divided into heart-related and non-heart-related pain. Pain due to insufficient blood flow to the heart is also called angina pectoris. Those with diabetes or the elderly may have less clear symptoms.

Atrial septal defect (ASD) is a congenital heart defect in which blood flows between the atria of the heart. Some flow is a normal condition both pre-birth and immediately post-birth via the foramen ovale; however, when this does not naturally close after birth it is referred to as a patent (open) foramen ovale (PFO). It is common in patients with a congenital atrial septal aneurysm (ASA).

Coronary thrombosis is defined as the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel of the heart. This blood clot may then restrict blood flow within the heart, leading to heart tissue damage, or a myocardial infarction, also known as a heart attack.

Dressler syndrome is a secondary form of pericarditis that occurs in the setting of injury to the heart or the pericardium. It consists of fever, pleuritic pain, pericarditis and/or pericardial effusion.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a syndrome due to decreased blood flow in the coronary arteries such that part of the heart muscle is unable to function properly or dies. The most common symptom is centrally located pressure-like chest pain, often radiating to the left shoulder or angle of the jaw, and associated with nausea and sweating. Many people with acute coronary syndromes present with symptoms other than chest pain, particularly women, older people, and people with diabetes mellitus.

An embolus, is described as a free-floating mass, located inside blood vessels that can travel from one site in the blood stream to another. An embolus can be made up of solid, liquid, or gas. Once these masses get "stuck" in a different blood vessel, it is then known as an "embolism." An embolism can cause ischemia—damage to an organ from lack of oxygen. A paradoxical embolism is a specific type of embolism in which the embolus travels from the right side of the heart to the left side of the heart and lodges itself in a blood vessel known as an artery. Thus, it is termed "paradoxical" because the embolus lands in an artery, rather than a vein.

The intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) is a mechanical device that increases myocardial oxygen perfusion and indirectly increases cardiac output through afterload reduction. It consists of a cylindrical polyurethane balloon that sits in the aorta, approximately 2 centimeters (0.79 in) from the left subclavian artery. The balloon inflates and deflates via counter pulsation, meaning it actively deflates in systole and inflates in diastole. Systolic deflation decreases afterload through a vacuum effect and indirectly increases forward flow from the heart. Diastolic inflation increases blood flow to the coronary arteries via retrograde flow. These actions combine to decrease myocardial oxygen demand and increase myocardial oxygen supply.

Bivalirudin (Bivalitroban), sold under the brand names Angiomax and Angiox and manufactured by The Medicines Company, is a direct thrombin inhibitor (DTI).

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or takotsubo syndrome (TTS), also known as stress cardiomyopathy, is a type of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy in which there is a sudden temporary weakening of the muscular portion of the heart. It usually appears after a significant stressor, either physical or emotional; when caused by the latter, the condition is sometimes called broken heart syndrome. Examples of physical stressors that can cause TTS are sepsis, shock, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and pheochromocytoma. Emotional stressors include bereavement, divorce, or the loss of a job. Reviews suggest that of patients diagnosed with the condition, about 70–80% recently experienced a major stressor, including 41–50% with a physical stressor and 26–30% with an emotional stressor. TTS can also appear in patients who have not experienced major stressors.

Myocardial rupture is a laceration of the ventricles or atria of the heart, of the interatrial or interventricular septum, or of the papillary muscles. It is most commonly seen as a serious sequela of an acute myocardial infarction.

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops in the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may travel into the shoulder, arm, back, neck or jaw. Often it occurs in the center or left side of the chest and lasts for more than a few minutes. The discomfort may occasionally feel like heartburn. Other symptoms may include shortness of breath, nausea, feeling faint, a cold sweat or feeling tired. About 30% of people have atypical symptoms. Women more often present without chest pain and instead have neck pain, arm pain or feel tired. Among those over 75 years old, about 5% have had an MI with little or no history of symptoms. An MI may cause heart failure, an irregular heartbeat, cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest.

ST depression refers to a finding on an electrocardiogram, wherein the trace in the ST segment is abnormally low below the baseline.

Primary ventricular fibrillation (PVF) is an unpredictable and potentially fatal arrhythmia occurring during the acute phase of a myocardial infarction leading to immediate collapse and, if left untreated, leads to sudden cardiac death within minutes. In developed countries, PVF is a leading cause of death. Worldwide, the annual number of deaths caused by PVF is comparable to the number of deaths caused by road traffic accidents. A substantial portion of these deaths could be avoided by seeking immediate medical attention when symptoms are noticed.

Reperfusion therapy is a medical treatment to restore blood flow, either through or around, blocked arteries, typically after a heart attack. Reperfusion therapy includes drugs and surgery. The drugs are thrombolytics and fibrinolytics used in a process called thrombolysis. Surgeries performed may be minimally-invasive endovascular procedures such as a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), which involves coronary angioplasty. The angioplasty uses the insertion of a balloon and/or stents to open up the artery. Other surgeries performed are the more invasive bypass surgeries that graft arteries around blockages.

Electrocardiography in suspected myocardial infarction has the main purpose of detecting ischemia or acute coronary injury in emergency department populations coming for symptoms of myocardial infarction (MI). Also, it can distinguish clinically different types of myocardial infarction.

Myocardial infarction complications may occur immediately following a heart attack, or may need time to develop. After an infarction, an obvious complication is a second infarction, which may occur in the domain of another atherosclerotic coronary artery, or in the same zone if there are any live cells left in the infarct.

Management of acute coronary syndrome is targeted against the effects of reduced blood flow to the affected area of the heart muscle, usually because of a blood clot in one of the coronary arteries, the vessels that supply oxygenated blood to the myocardium. This is achieved with urgent hospitalization and medical therapy, including drugs that relieve chest pain and reduce the size of the infarct, and drugs that inhibit clot formation; for a subset of patients invasive measures are also employed. Basic principles of management are the same for all types of acute coronary syndrome. However, some important aspects of treatment depend on the presence or absence of elevation of the ST segment on the electrocardiogram, which classifies cases upon presentation to either ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NST-ACS); the latter includes unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Treatment is generally more aggressive for STEMI patients, and reperfusion therapy is more often reserved for them. Long-term therapy is necessary for prevention of recurrent events and complications.

Impella is a family of medical devices used for temporary ventricular support in patients with depressed heart function. Some versions of the device can provide left heart support during other forms of mechanical circulatory support including ECMO and Centrimag.

The volume of the heart's left atrium is an important biomarker for cardiovascular physiology and clinical cardiology. It is usually calculated as left atrial volume index in terms of body surface area.