Related Research Articles

A modern melodrama is a dramatic work in which plot, typically sensationalized for a strong emotional appeal, takes precedence over detailed characterization. Melodrama is "an exaggerated version of drama". Melodramas typically concentrate on dialogue that is often bombastic or excessively sentimental, rather than on action. Characters are often flat and written to fulfill established character archetypes. Melodramas are typically set in the private sphere of the home, focusing on morality, family issues, love, and marriage, often with challenges from an outside source, such as a "temptress", a scoundrel, or an aristocratic villain. A melodrama on stage, film, or television is usually accompanied by dramatic and suggestive music that offers further cues to the audience of the dramatic beats being presented.

A burlesque is a literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works, or by ludicrous treatment of their subjects. The word derives from the Italian burlesco, which, in turn, is derived from the Italian burla – a joke, ridicule or mockery.

A closet drama is a play that is not intended to be performed onstage, but read by a solitary reader. The earliest use of the term recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary is in 1813. The literary historian Henry A. Beers in 1907 considered closet drama "a quite legitimate product of literary art."

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street and backs onto Drury Lane. The present building, opened in 1812, is the most recent of four theatres that stood at the location since 1663, making it the oldest theatre site in London still in use. According to the author Peter Thomson, for its first two centuries, Drury Lane could "reasonably have claimed to be London's leading theatre". For most of that time, it was one of a handful of patent theatres, granted monopoly rights to the production of "legitimate" drama in London.

Sir Francis Cowley Burnand, usually known as F. C. Burnand, was an English comic writer and prolific playwright, best known today as the librettist of Arthur Sullivan's opera Cox and Box.

A wide range of movements existed in the theatrical culture of Europe and the United States in the 19th century. In the West, they include Romanticism, melodrama, the well-made plays of Scribe and Sardou, the farces of Feydeau, the problem plays of Naturalism and Realism, Wagner's operatic Gesamtkunstwerk, Gilbert and Sullivan's plays and operas, Wilde's drawing-room comedies, Symbolism, and proto-Expressionism in the late works of August Strindberg and Henrik Ibsen.

Po-ca-hon-tas, or The Gentle Savage is a two-act musical burlesque by John Brougham (words) and James Gaspard Maeder (music). It debuted in 1855 and became an instant hit. Po-ca-hon-tas remained a staple of theatre troupes and blackface minstrel companies for the next 30 years, typically as an afterpiece.

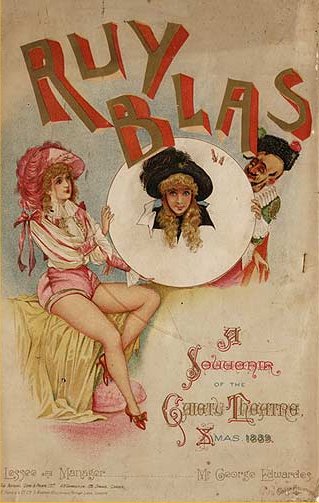

Victorian burlesque, sometimes known as travesty or extravaganza, is a genre of theatrical entertainment that was popular in Victorian England and in the New York theatre of the mid-19th century. It is a form of parody in which a well-known opera or piece of classical theatre or ballet is adapted into a broad comic play, usually a musical play, usually risqué in style, mocking the theatrical and musical conventions and styles of the original work, and often quoting or pastiching text or music from the original work. Victorian burlesque is one of several forms of burlesque.

Dumbshow, also dumb show or dumb-show, is defined by the Oxford Dictionary of English as "gestures used to convey a meaning or message without speech; mime." In the theatre the word refers to a piece of dramatic mime in general, or more particularly a piece of action given in mime within a play "to summarise, supplement, or comment on the main action".

In theater and music history, a burletta is a brief comic opera. In eighteenth-century Italy, a burletta was the comic intermezzo between the acts of an opera seria. The extended work Pergolesi's La serva padrona was also designated a "burletta" at its London premiere in 1758.

Immodesty Blaize is an English burlesque dancer who performs internationally. She was crowned Reigning Queen of Burlesque in June 2007 at the Las Vegas Burlesque Hall of Fame formerly known as Exotic World.

Theatre of United Kingdom plays an important part in British culture, and the countries that constitute the UK have had a vibrant tradition of theatre since the Renaissance with roots going back to the Roman occupation.

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The performers may communicate this experience to the audience through combinations of gesture, speech, song, music, and dance. It is the oldest form of drama, though live theatre has now been joined by modern recorded forms. Elements of art, such as painted scenery and stagecraft such as lighting are used to enhance the physicality, presence and immediacy of the experience. Places, normally buildings, where performances regularly take place are also called "theatres", as derived from the Ancient Greek θέατρον, itself from θεάομαι.

American burlesque is a genre of variety show derived from elements of Victorian burlesque, music hall, and minstrel shows. Burlesque became popular in the United States in the late 1860s and slowly evolved to feature ribald comedy and female nudity. By the late 1920s, the striptease element overshadowed the comedy and subjected burlesque to extensive local legislation. Burlesque gradually lost its popularity, beginning in the 1940s. A number of producers sought to capitalize on nostalgia for the entertainment by recreating burlesque on the stage and in Hollywood films from the 1930s to the 1960s. There has been a resurgence of interest in this format since the 1990s.

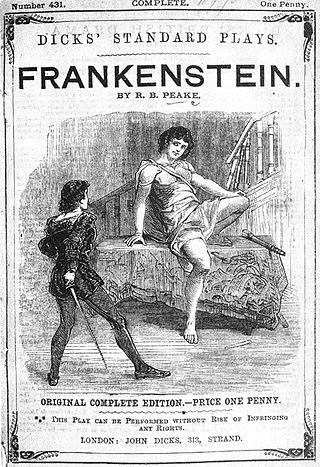

Richard Brinsley Peake was a dramatist of the early nineteenth century best remembered today for his 1823 play Presumption; or, the Fate of Frankenstein, a work based on the novel Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. It was Peake, not Shelley, who wrote the famous line, "It lives!"

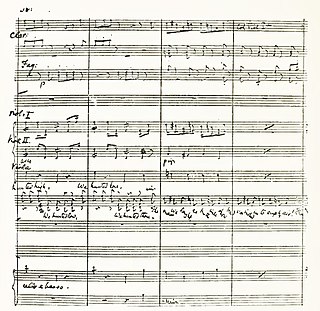

Theatre music refers to a wide range of music composed or adapted for performance in theatres. Genres of theatre music include opera, ballet and several forms of musical theatre, from pantomime to operetta and modern stage musicals and revues. Another form of theatre music is incidental music, which, as in radio, film and television, is used to accompany the action or to separate the scenes of a play. The physical embodiment of the music is called a score, which includes the music and, if there are lyrics, it also shows the lyrics.

Parsi theatre is a generic term for an influential theatre tradition, staged by Parsis, and theatre companies largely-owned by the Parsi business community, which flourished between 1850 and the 1930s. Plays were primarily in the Hindustani language, as well as Gujarati to an extent. After its beginning in Bombay, it soon developed into various travelling theatre companies, which toured across India, especially north and western India, popularizing proscenium-style theatre in regional languages.

William Fisher Peach Dimond was a playwright of the early 19th-century who wrote about thirty works for the theatre, including plays, operas, musical entertainments and melodramas.

Alice Oates was an actress, theatre manager and pioneer of American musical theatre who took opéra bouffe in English to all corners of America. She produced the first performance of a work by Gilbert and Sullivan in America with her unauthorised Trial by Jury in 1875, the first American production of The Sultan of Mocha (1878) and an early performance of H.M.S. Pinafore (1878).

Olympic Theatre was the name of five former 19th and early 20th-century theatres on Broadway in Manhattan and in Brooklyn, New York.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jess Stein, ed. "Legitimate" entry. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language. Random House, 1966. p. 819. "—adj. 8. Theat. of or pertaining to professionally produced stage plays, as distinguished from burlesque, vaudeville, television, motion pictures, etc.: legitimate drama. ... —n. 'the legitimate', the legitimate theater or drama."

- 1 2 3 Joyce M. Hawkins and Robert Allen, eds. "Legitimate" entry. The Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1991. pp. 820-821. "—adj. 5. constituting or relating to serious drama (including both comedy and tragedy) as distinct from musical comedy, farce, revue, etc. The term arose in the 18th c. ... It covered plays dependent entirely on acting with little or no singing, dancing or spectacle."

- 1 2 3 4 Mark Hodin. "The Disavowal of Ethnicity: Legitimate Theatre and the Social Construction of Literary Value in Turn-of-the-Century America." Theatre Journal.52.2: May 2000. p. 212. JSTOR 25068777 "The expression legitimate theatre...became vernacular within [the] turn-of-the-[20th]-century amusement market. The legitimate prefix confirmed the fact that conventional stage plays no longer monopolized the definition of legitimate theatrical entertainment, while, at the same time, asserted that they did (or could), as a strategy for profiting under these new conditions. As such, legitimate theatre referred to the history of theatre's high-cultural place, most directly to the authority invested in the Patent playhouses of eighteenth century Britain, but it also suggested the sort of literariness associated with legitimate drama, a term familiar to British and American playgoers, actors, and critics in the nineteenth century for distinguishing classic plays (Shakespeare, Molière, Sheridan) from the contemporary melodramas they also enjoyed. As it does today, however, legitimate theatre made no distinction between good and bad plays; what it proposed and promoted was that, in relation to other competing forms of commercial amusement, the particular value of conventionally staged drama was that it provided the best occasion and opportunity available for acquiring cultural prestige, "literary" value, commercially."

- 1 2 3 Phyllis Hartnoll and Peter Found, eds. "Legitimate Drama " entry. The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780192825742

- ↑ Joyce M. Hawkins and Robert Allen, eds. "Legit" entry. The Oxford Encyclopedic English Dictionary. Clarendon Press, 1991. pp. 820. "—n. 1. legitimate drama. 2. an actor in a legitimate drama. [abbr.]"

- ↑ Mark Hodin. "The Disavowal of Ethnicity: Legitimate Theatre and the Social Construction of Literary Value in Turn-of-the-Century America." Theatre Journal.52.2: May 2000. p. 213. JSTOR 25068777

- ↑ Grantley, Darryll (10 October 2013). Historical Dictionary of British Theatre: Early Period. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810880283 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- 1 2 Michael R. Booth. "Legitimate drama" entry. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance. Dennis Kennedy, ed. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780198601746 "After 1843 and the Theatres Regulation Act, whereby any theatre could play any kind of drama it wished, subject to the censorship powers of the Lord Chamberlain, the distinction between 'legitimate' and 'illegitimate' ceased to have any meaning."

- ↑ Harrison, Martin (1 January 1998). The Language of Theatre. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780878300877 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Wyndham, Henry Saxe (21 November 2013). The Annals of Covent Garden Theatre from 1732 to 1897. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108068680 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Everett Wilson. "Favorite Things: Legitimate Theatre", The Partial Observer, 5 November 2005. Archived copy. Archived on 28 September 2007. Accessed 20 July 2022.

- ↑ Knox, Paul (5 November 2012). Palimpsests: Biographies of 50 City Districts. International Case Studies of Urban Change. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783034612128 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ "School of Music, Theatre & Dance Programs". University of Michigan School of Music. 1 January 1996. Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Wearing, J. P. (21 November 2013). The London Stage 1890-1899: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810892828 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Davis, Derek Russell (11 September 2002). Scenes of Madness: A Psychiatrist at the Theatre. Routledge. ISBN 9781134789009 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Law, Jonathan (16 December 2013). The Methuen Drama Dictionary of the Theatre. A&C Black. ISBN 9781408131480 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Trussler, Simon (21 September 2000). The Cambridge Illustrated History of British Theatre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521794305 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.

- ↑ Sova, Dawn B. (1 January 2004). Banned Plays: Censorship Histories of 125 Stage Dramas. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438129938 . Retrieved 20 November 2016– via Google Books.