Related Research Articles

In Greek mythology, Silenus was a companion and tutor to the wine god Dionysus. He is typically older than the satyrs of the Dionysian retinue (thiasos), and sometimes considerably older, in which case he may be referred to as a Papposilenus. Silen and its plural sileni refer to the mythological figure as a type that is sometimes thought to be differentiated from a satyr by having the attributes of a horse rather than a goat, though usage of the two words is not consistent enough to permit a sharp distinction.

The Bacchanali were unofficial, privately funded popular Roman festivals of Bacchus, based on various ecstatic elements of the Greek Dionysia. They were almost certainly associated with Rome's native cult of Liber, and probably arrived in Rome itself around 200 BC. Like all mystery religions of the ancient world, very little is known of their rites. They seem to have been popular and well-organised throughout the central and southern Italian peninsula.

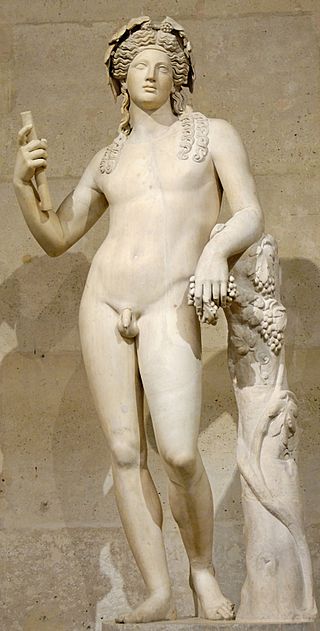

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus is the god of wine-making, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, festivity, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre. He was also known as Bacchus by the Greeks for a frenzy he is said to induce called baccheia. As Dionysus Eleutherius, his wine, music, and ecstatic dance free his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subvert the oppressive restraints of the powerful. His thyrsus, a fennel-stem sceptre, sometimes wound with ivy and dripping with honey, is both a beneficent wand and a weapon used to destroy those who oppose his cult and the freedoms he represents. Those who partake of his mysteries are believed to become possessed and empowered by the god himself.

In Greek mythology, maenads were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of his retinue, the thiasus. Their name, which comes from μαίνομαι, literally translates as 'raving ones'. Maenads were known as Bassarids, Bacchae, or Bacchantes in Roman mythology after the penchant of the equivalent Roman god, Bacchus, to wear a bassaris or fox skin.

In ancient Greek religion and mythology, Iacchus was a minor deity, of some cultic importance, particularly at Athens and Eleusis in connection with the Eleusinian mysteries, but without any significant mythology. He perhaps originated as the personification of the ritual exclamation Iacche! cried out during the Eleusinian procession from Athens to Eleusis. He was often identified with Dionysus, perhaps because of the resemblance of the names Iacchus and Bacchus, another name for Dionysus. By various accounts he was a son of Demeter, or a son of Persephone, identical with Dionysus Zagreus, or a son of Dionysus.

The Anthesteria was one of the four Athenian festivals in honor of Dionysus. It was held each year from the 11th to the 13th of the month of Anthesterion, around the time of the January or February full moon. The three days of the feast were called Pithoigia, Choës, and Chytroi.

The Dionysia was a large festival in ancient Athens in honor of the god Dionysus, the central events of which were the theatrical performances of dramatic tragedies and, from 487 BC, comedies. It was the second-most important festival after the Panathenaia. The Dionysia actually consisted of two related festivals, the Rural Dionysia and the City Dionysia, which took place in different parts of the year.

A theatrical culture flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. At its centre was the city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, and the theatre was institutionalised there as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus. Tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play were the three dramatic genres emerged there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies. Modern Western theatre comes, in large measure, from the theatre of ancient Greece, from which it borrows technical terminology, classification into genres, and many of its themes, stock characters, and plot elements.

Greek tragedy is one of the three principal theatrical genres from Ancient Greece and Greek-inhabited Anatolia, along with comedy and the satyr play. It reached its most significant form in Athens in the 5th century BC, the works of which are sometimes called Attic tragedy.

Eleutherae is a city in the northern part of Attica, bordering the territory of Boeotia. One of the best preserved fortresses of Ancient Greece stands now on the spot of an Ancient Eleutherae castle, dated between 370 and 360 BC, with walls of very fine masonry that average 2.6m thick. A circuit of wall 860 m contained towers, 6 of them still standing along the northern edge of the site, preserved to the height of 4 to 6 m. The foundations of more towers are present. Although not as well preserved, the line of the remainder of the fortification circuit is clear, as is the location of the one large, double gate (western) and one small (south-eastern) gate. There are two small sally-ports located on the north side. The fortified area is irregular and c. 113 by 290m in extent.

The Theatre of Dionysus is an ancient Greek theatre in Athens. It is built on the south slope of the Acropolis hill, originally part of the sanctuary of Dionysus Eleuthereus. The first orchestra terrace was constructed on the site around the mid- to late-sixth century BC, where it hosted the City Dionysia. The theatre reached its fullest extent in the fourth century BC under the epistates of Lycurgus when it would have had a capacity of up to 25,000, and was in continuous use down to the Roman period. The theatre then fell into decay in the Byzantine era and was not identified, excavated and restored to its current condition until the nineteenth century.

The satyr play is a form of Attic theatre performance related to both comedy and tragedy. It preserves theatrical elements of dialogue, actors speaking verse, a chorus that dances and sings, masks and costumes. Its relationship to tragedy is strong; satyr plays were written by tragedians, and satyr plays were performed in the Dionysian festival following the performance of a group of three tragedies. The satyr play's mythological-heroic stories and the style of language are similar to that of the tragedies. Its connection with comedy is also significant – it has similar plots, titles, themes, characters, and happy endings. The remarkable feature of the satyr play is the chorus of satyrs, with their costumes that focus on the phallus, and with their language, which uses wordplay, sexual innuendos, references to breasts, farting, erections, and other references that do not occur in tragedy. As Mark Griffith points out, the satyr play was "not merely a deeply traditional Dionysiac ritual, but also generally accepted as the most appropriate and satisfying conclusion to the city’s most complex and prestigious cultural event of the year."

In Greek mythology and religion, the thiasus was the ecstatic retinue of Dionysus, often pictured as inebriated revelers. Many of the myths of Dionysus are connected with his arrival in the form of a procession. The grandest such version was his triumphant return from "India", which influenced symbolic conceptions of the Roman triumph and was narrated in rapturous detail in Nonnus's Dionysiaca. In this procession, Dionysus rides a chariot, often drawn by big cats such as tigers, leopards, or lions, or alternatively elephants or centaurs.

The Dionysian Mysteries were a ritual of ancient Greece and Rome which sometimes used intoxicants and other trance-inducing techniques to remove inhibitions. It also provided some liberation for men and women marginalized by Greek society, among which were slaves, outlaws, and non-citizens. In their final phase the Mysteries shifted their emphasis from a chthonic, underworld orientation to a transcendental, mystical one, with Dionysus changing his nature accordingly. By its nature as a mystery religion reserved for the initiated, many aspects of the Dionysian cult remain unknown and were lost with the decline of Greco-Roman polytheism; modern knowledge is derived from descriptions, imagery and cross-cultural studies.

Gerarai, also known by the latinized form Gerarae, were priestesses (Hiereiai) of Dionysus in ancient Greek religion.

The cult of Dionysus was strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni, and its characteristic symbols were the bull, the serpent, tigers/leopards, ivy, and wine. The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus, as well as the phallic processions. Initiates worshipped him in the Dionysian Mysteries, which were comparable to and linked with the Orphic Mysteries, and may have influenced Gnosticism. Orpheus was said to have invented the Mysteries of Dionysus. It is possible that water divination was an important aspect of worship within the cult.

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance: a play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on radio or television. Considered as a genre of poetry in general, the dramatic mode has been contrasted with the epic and the lyrical modes ever since Aristotle's Poetics —the earliest work of dramatic theory.

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present experiences of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The performers may communicate this experience to the audience through combinations of gesture, speech, song, music, and dance. It is the oldest form of drama, though live theatre has now been joined by modern recorded forms. Elements of art, such as painted scenery and stagecraft such as lighting are used to enhance the physicality, presence and immediacy of the experience. Places, normally buildings, where performances regularly take place are also called "theatres", as derived from the Ancient Greek θέατρον, itself from θεάομαι.

The history of theatre charts the development of theatre over the past 2,500 years. While performative elements are present in every society, it is customary to acknowledge a distinction between theatre as an art form and entertainment, and theatrical or performative elements in other activities. The history of theatre is primarily concerned with the origin and subsequent development of the theatre as an autonomous activity. Since classical Athens in the 5th century BC, vibrant traditions of theatre have flourished in cultures across the world.

The festival calendar of Classical Athens involved the staging of many festivals each year. This includes festivals held in honor of Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hermes, and Herakles. Other Athenian festivals were based around family, citizenship, sacrifice, and women. There were at least 120 festival days each year.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Brockett and Hildy (2003, 20).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Valdés Guía, Miriam (2013), "Redefining Dionysos in Athens from the Written Sources: The Lenaia, Iacchos and Attic Women", Redefining Dionysos, Berlin, Boston: DE GRUYTER, pp. 100–119, doi:10.1515/9783110301328.100, ISBN 978-3-11-030132-8

- ↑ Csapo and Slater (1998, 123)

- 1 2 Swallow, Peter. "Reconstructing the Lenaia" . Retrieved 2016-03-13.