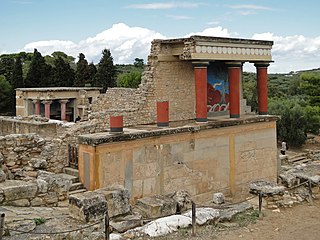

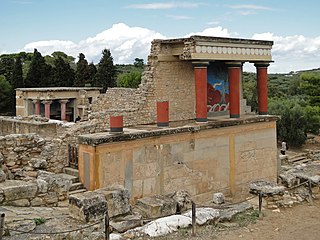

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos are popular tourist attractions.

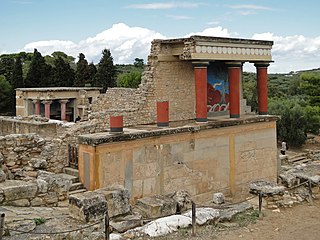

Knossos is a Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. The site was a major center of the Minoan civilization and is known for its association with the Greek myth of Theseus and the minotaur. It is located on the outskirts of Heraklion, and remains a popular tourist destination.

Bull-leaping is a term for various types of non-violent bull fighting. Some are based on an ancient ritual from the Minoan civilization involving an acrobat leaping over the back of a charging bull. As a sport it survives in modern France, usually with cows rather than bulls, as course landaise; in Spain, with bulls, as recortes and in Tamil Nadu, India with bulls as Jallikattu.

Aegean art is art that was created in the lands surrounding, and the islands within, the Aegean Sea during the Bronze Age, that is, until the 11th century BC, before Ancient Greek art. Because is it mostly found in the territory of modern Greece, it is sometimes called Greek Bronze Age art, though it includes not just the art of the Mycenaean Greeks, but also that of the Cycladic and Minoan cultures, which converged over time.

Pseira is an islet in the Gulf of Mirabello in northeastern Crete with the archaeological remains of Minoan and Mycenean civilisation.

Minoan pottery has been used as a tool for dating the mute Minoan civilization. Its restless sequence of quirky maturing artistic styles reveals something of Minoan patrons' pleasure in novelty while they assist archaeologists in assigning relative dates to the strata of their sites. Pots that contained oils and ointments, exported from 18th century BC Crete, have been found at sites through the Aegean islands and mainland Greece, in Cyprus, along coastal Syria and in Egypt, showing the wide trading contacts of the Minoans.

Amnisos, also Amnissos and Amnisus, is the current but unattested name given to a Bronze Age settlement on the north shore of Crete that was used as a port to the palace city of Knossos. It appears in Greek literature and mythology from the earliest times, but its origin is far earlier, in prehistory. The historic settlement belonged to a civilization now called Minoan. Excavations at Amnissos in 1932 uncovered a villa that included the "House of the Lilies", which was named for the lily theme that was depicted in a wall fresco.

Phourni is the archaeological site of an ancient Minoan cemetery in Crete, established in 2400 BC and lasted until 1200 BC. Phourni is Greek for "furnace, oven" and the name of the hill on which the cemetery is located. Phourni is located at 70100 Epano Archanes, Heraklion, Greece—located on a hill in north-central Crete. Phourni can be seen from Mount Juktas. It is a small hill situated northwest of Archanes, between Archanes and Kato Archanes. Phourni is reachable from a signed scenic path that starts at Archanes. It was an important site for Minoan burials. The burials consistently and proactively engaged the community of the Minoans. The largest cemetery in the Archanes area was discovered in 1957 and excavated for 25 years by Yiannis Sakellarakis, beginning in 1965. The 6600 sq m cemetery includes 26 funerary buildings of varying shapes and sizes. The necropolis of Phourni is of primary importance, both for the duration of its use and for the variety of its funerary monuments. All the pottery and much of the skeletal material was collected, unlike many other pre-palatial tombs. The cemetery was founded in the Ancient Minoan IIA, and continued to be used until the end of the Bronze Age. The occupation reached its peak during the Middle Minoan AI, just before the palaces of Knossos and Malia appeared. The proximity of Archanes to the important religious centres of Mount Iuktas probably contributed to the prominence of the site.

Vaphio, Vafio or Vapheio is an ancient site in Laconia, Greece, on the right bank of the Eurotas, some 5 mi (8.0 km) south of Sparta. It is famous for its tholos or beehive tomb, excavated in 1889 by Christos Tsountas. This consists of a walled approach, about 97 ft (30 m) long, leading to a vaulted chamber some 33 ft (10 m) in diameter, in the floor of which the actual grave was cut. The tomb suffered considerable damage in the decades following its excavation. During conservation work in 1962 the walls were restored to a height of about 6 m (20 ft).

The Heraklion Archaeological Museum is a museum located in Heraklion on Crete. It is one of the largest museums in Greece and the best in the world for Minoan art, as it contains by far the most important and complete collection of artefacts of the Minoan civilization of Crete. It is normally referred to scholarship in English as "AMH", a form still sometimes used by the museum in itself.

Minoan chronology is a framework of dates used to divide the history of the Minoan civilization. Two systems of relative chronology are used for the Minoans. One is based on sequences of pottery styles, while the other is based on the architectural phases of the Minoan palaces. These systems are often used alongside one another.

Minoan religion was the religion of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization of Crete. In the absence of readable texts from most of the period, modern scholars have reconstructed it almost totally on the basis of archaeological evidence of such as Minoan paintings, statuettes, vessels for rituals and seals and rings. Minoan religion is considered to have been closely related to Near Eastern ancient religions, and its central deity is generally agreed to have been a goddess, although a number of deities are now generally thought to have been worshipped. Prominent Minoan sacred symbols include the bull and the horns of consecration, the labrys double-headed axe, and possibly the serpent.

Mycenaean pottery is the pottery tradition associated with the Mycenaean period in Ancient Greece. It encompassed a variety of styles and forms including the stirrup jar. The term "Mycenaean" comes from the site Mycenae, and was first applied by Heinrich Schliemann.

Kamares ware is a distinctive type of Minoan pottery produced in Crete during the Minoan period, dating to MM IA. By the LM IA period, or the end of the First Palace Period, these wares decline in distribution and "vitality". They have traditionally been interpreted as a prestige artifact, possibly used as an elite table-ware.

Minoan art is the art produced by the Bronze Age Aegean Minoan civilization from about 3000 to 1100 BC, though the most extensive and finest survivals come from approximately 2300 to 1400 BC. It forms part of the wider grouping of Aegean art, and in later periods came for a time to have a dominant influence over Cycladic art. Since wood and textiles have decomposed, the best-preserved surviving examples of Minoan art are its pottery, palace architecture, small sculptures in various materials, jewellery, metal vessels, and intricately-carved seals.

Minoan palaces were massive building complexes built on Crete during the Bronze Age. They are often considered emblematic of the Minoan civilization and are modern tourist destinations. Archaeologists generally recognize five structures as palaces, namely those at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, Galatas, and Zakros. Minoan palaces consisted of multistory wings surrounding an open rectangular central court. They shared a common architectural vocabulary and organization, including distinctive room types such as the lustral basin and the pillar crypt. However, each palace was unique, and their appearances changed dramatically as they were continually remodeled throughout their lifespans.

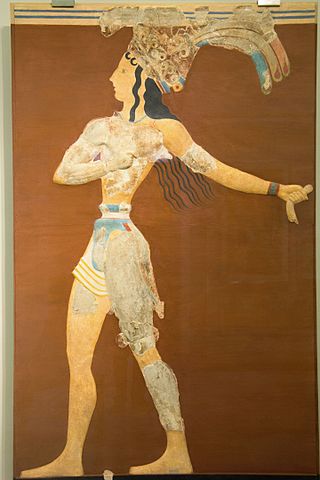

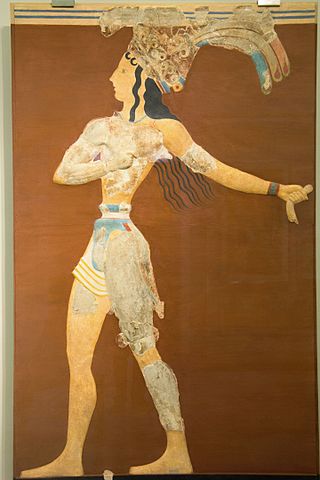

The Prince of the Lilies, or the Lily Prince or Priest-King Fresco, is a celebrated Minoan painting excavated in pieces from the palace of Knossos, capital of the Bronze Age Minoan civilization on the Greek island of Crete. The mostly reconstructed original is now in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum (AMH), with a replica version at the palace which includes flowers in the background.

Minoan seals are impression seals in the form of carved gemstones and similar pieces in metal, ivory and other materials produced in the Minoan civilization. They are an important part of Minoan art, and have been found in quantity at specific sites, for example in Knossos, Mallia and Phaistos. They were evidently used as a means of identifying documents and objects.

The Minoan bull leaper is a bronze group of a bull and leaper in the British Museum. It is the only known largely complete three-dimensional sculpture depicting Minoan bull-leaping. Although bull leaping certainly took place in Crete at this time, the leap depicted is practically impossible and it has therefore been speculated that the sculpture may be an exaggerated depiction. This speculation has been backed up by the testaments of modern-day bull leapers from France and Spain.

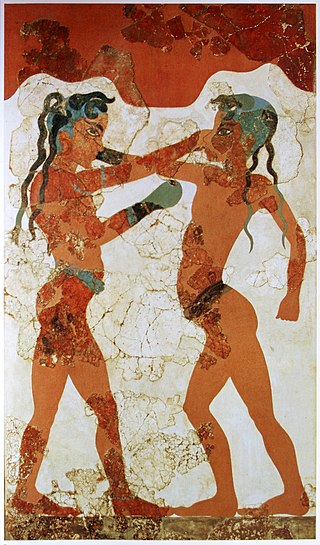

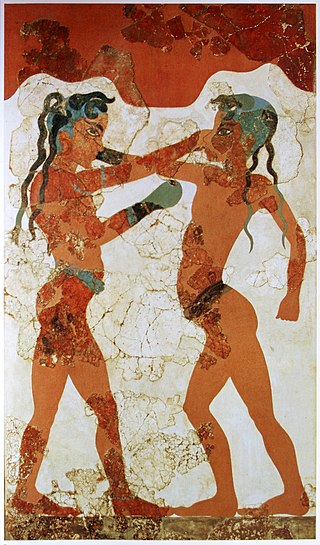

The Minoan civilization in the Bronze Age was located on the island of Crete. Focusing on the palatial periods between c. 1900 and c. 1300 b.c.. Art that focuses on just scenes of war alone is impossible as there are many other references that can be made not relating to war at all. There are various meanings that can be interpreted from different perspectives and that is what Molloy wants readers to understand. There could be an overlap of religion, politics, social meanings added to an iconography of warfare. “Practitioners of violence” are called warriors, just an identity who performed their social acts depending on their society. These social acts ranges from bull-leaping, boxing, hunting, sports, combat, fighting and more. Malloy divides the art relating to warfare in Bronze Age Crete into four categories “glyptic art circulating in both social and administrative contexts; stone and ceramic portable art for repeated intimate consumption (dining/processions); coroplastic/bronze figural art for religious activity; and frescoes and relief mouldings fixed in architectural settings”.