Related Research Articles

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthaginians, and Romans, among others. Crucifixion has been used in some countries as recently as the early 20th century.

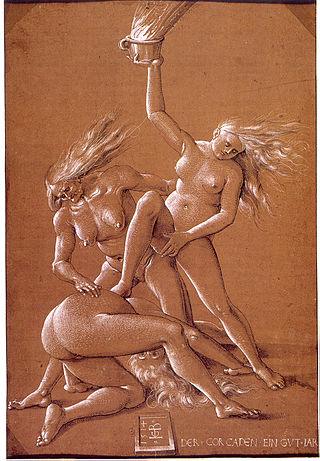

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the Middle East. In medieval Europe, witch-hunts often arose in connection to charges of heresy from Christianity. An intensive period of witch-hunts occurring in Early Modern Europe and to a smaller extent Colonial America, took place about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Counter Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 50,000 executions. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

Praetor, also pretor, was the title granted by the government of Ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected magistratus (magistrate), assigned to discharge various duties. The functions of the magistracy, the praetura (praetorship), are described by the adjective itself: the praetoria potestas, the praetorium imperium, and the praetorium ius, the legal precedents established by the praetores (praetors). Praetorium, as a substantive, denoted the location from which the praetor exercised his authority, either the headquarters of his castra, the courthouse (tribunal) of his judiciary, or the city hall of his provincial governorship. The minimum age for holding the praetorship was 39 during the Roman Republic, but it was later changed to 30 in the early Empire.

Proscription is, in current usage, a 'decree of condemnation to death or banishment' and can be used in a political context to refer to state-approved murder or banishment. The term originated in Ancient Rome, where it included public identification and official condemnation of declared enemies of the state and it often involved confiscation of property.

Dismemberment is the act of completely disconnecting and or removing the limbs from a living or dead being. It has been practiced upon human beings as a form of capital punishment, especially in connection with regicide, but can occur as a result of a traumatic accident, or in connection with murder, suicide, or cannibalism. As opposed to surgical amputation of limbs, dismemberment is often fatal. In criminology, a distinction is made between offensive dismemberment, in which dismemberment is the primary objective of the dismemberer, and defensive dismemberment, in which the motivation is to destroy evidence.

The Mamertine Prison, in antiquity the Tullianum, was a prison (carcer) with a dungeon (oubliette) located in the Comitium in ancient Rome. It is said to have been built in the 7th century BC and was situated on the northeastern slope of the Capitoline Hill, facing the Curia and the imperial forums of Nerva, Vespasian, and Augustus. Located between it and the Tabularium were the Gemonian stairs leading to the Arx of the Capitoline.

The law of majestas, or lex maiestatis, encompasses several ancient Roman laws throughout the Republican and Imperial periods dealing with crimes against the Roman people, state, or Emperor.

Sexual attitudes and behaviors in ancient Rome are indicated by art, literature, and inscriptions, and to a lesser extent by archaeological remains such as erotic artifacts and architecture. It has sometimes been assumed that "unlimited sexual license" was characteristic of ancient Rome, but sexuality was not excluded as a concern of the mos maiorum, the traditional social norms that affected public, private, and military life. Pudor, "shame, modesty", was a regulating factor in behavior, as were legal strictures on certain sexual transgressions in both the Republican and Imperial periods. The censors—public officials who determined the social rank of individuals—had the power to remove citizens from the senatorial or equestrian order for sexual misconduct, and on occasion did so. The mid-20th-century sexuality theorist Michel Foucault regarded sex throughout the Greco-Roman world as governed by restraint and the art of managing sexual pleasure.

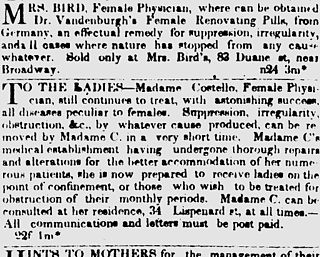

The practice of induced abortion—the deliberate termination of a pregnancy—has been known since ancient times. Various methods have been used to perform or attempt abortion, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques. The term abortion, or more precisely spontaneous abortion, is sometimes used to refer to a naturally occurring condition that ends a pregnancy, that is, to what is popularly called a miscarriage. But in what follows the term abortion will always refer to an induced abortion.

The concept of rape, both as an abduction and in the sexual sense, makes its appearance in early religious texts.

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

In Islamic law, Ḥirābah is a legal category that comprises highway robbery, rape, and terrorism. Ḥirābah means piracy or unlawful warfare. It comes from the triliteral root ḥrb, which means “to become angry and enraged”. The noun ḥarb means 'war' or 'wars'.

The use of capital punishment in Italy has been banned since 1889, with the exception of the period 1926–1947, encompassing the rule of Fascism in Italy and the early restoration of democracy. Before the unification of Italy in 1860, capital punishment was performed in almost all pre-unitarian states, except for Tuscany, where, starting from 1786, it was repeatedly abolished and reintroduced. It is currently prohibited by the Constitution of the Italian Republic with no more exceptions even in times of war.

The lex Calpurnia de repetundis was a Roman law sponsored in 149 BC by the tribune of the plebs Lucius Calpurnius Piso. It established the first permanent criminal court in Roman history, in order to deal with the growing number of crimes committed by Roman governors in the provinces. The lex Calpurnia was a milestone in both Roman law and politics.

Damnatio ad bestias was a form of Roman capital punishment where the condemned person was killed by wild animals, usually lions or other big cats. This form of execution, which first appeared during the Roman Republic around the 2nd century BC, had been part of a wider class of blood sports called Bestiarii.

The career of Julius Caesar before his consulship in 59 BC was characterized by military adventurism and political persecution. Julius Caesar was born on 12 July 100 BC into a patrician family, the gens Julia, which claimed descent from Iulus, son of the legendary Trojan prince Aeneas, supposedly the son of the goddess Venus. His father died when he was just 16, leaving Caesar as the head of the household. His family status put him at odds with the Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who almost had him executed.

In ancient Roman religion, the devotio was an extreme form of votum in which a Roman general vowed to sacrifice his own life in battle along with the enemy to chthonic gods in exchange for a victory. The most extended description of the ritual is given by the Augustan historian Livy, regarding the self-sacrifice of Decius Mus. The English word "devotion" derives from the Latin.

Poena cullei under Roman law was a type of death penalty imposed on a subject who had been found guilty of patricide. The punishment consisted of being sewn up in a leather sack, with an assortment of live animals including a dog, snake, monkey, and a chicken or rooster, and then being thrown into water.

In the later Roman Empire, honestiores and humiliores emerged as two broad distinctions of social and legal status, those who had held the higher offices (honores) and humbler people. The division starts to become apparent near the end of the 2nd century AD.

The proscription of Sulla was a reprisal campaign by the Roman proconsul and later dictator, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, to eliminate his enemies in the aftermath of his victory in the civil war of 83–82 BC.

References

- ↑ J.D. Cloud, 'How Did Sulla Style His Law de Sicariis?', Classical Review 18(2) (1968), 140-43.

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars, 1.99

- 1 2 3 Digest of Justinian, 48.8.2.

- ↑ Paulus, Sententiae, 5.23.14-9.

- ↑ D. Ogden, Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford: 2009. 279

- ↑ "LacusCurtius — Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ↑ P. Schafer, Judeophobia: Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Ancient World, Cambridge, Mass: 1997. 104.

- ↑ Origen, Contra Celsum, 2.13.