The Corpus JurisCivilis is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. It is also sometimes referred to metonymically after one of its parts, the Code of Justinian.

The Breviary of Alaric is a collection of Roman law, compiled by Roman jurists and issued by referendary Anianus on the order of Alaric II, King of the Visigoths, with the approval of his bishops and nobles. It was promulgated on 2 February 506, the 22nd year of his reign. It applied, not to the Visigothic nobles who lived under their own law, which had been formulated by Euric, but to the Hispano-Roman and Gallo-Roman population, living under Visigoth rule south of the Loire and, in Book 16, to the members of the trinitarian Catholic Church; the Visigoths were Arian and maintained their own clergy.

The Visigothic Code, also called Lex Visigothorum, is a set of laws first promulgated by king Chindasuinth of the Visigothic Kingdom in his second year of rule (642–643) that survives only in fragments. In 654 his son, king Recceswinth (649–672), published the enlarged law code, which was the first law code that applied equally to the conquering Goths and the general population, of which the majority had Roman roots, and had lived under Roman laws.

The Digest, also known as the Pandects, was a compendium or digest of juristic writings on Roman law compiled by order of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I in 530–533 AD. It is divided into 50 books.

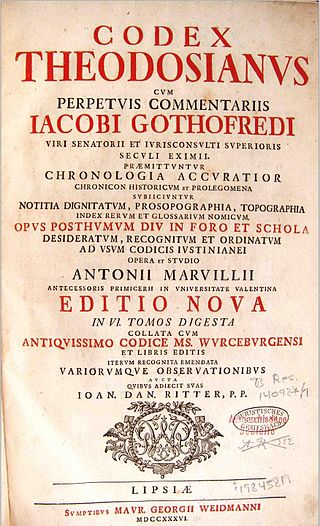

The Codex Theodosianus was a compilation of the laws of the Roman Empire under the Christian emperors since 312. A commission was established by Emperor Theodosius II and his co-emperor Valentinian III on 26 March 429 and the compilation was published by a constitution of 15 February 438. It went into force in the eastern and western parts of the empire on 1 January 439. The original text of the codex is also found in the Breviary of Alaric, promulgated on 2 February 506.

The Codex Euricianus or Code of Euric was a collection of laws governing the Visigoths compiled at the order of Euric, King of the Visigoths, sometime before 480, probably at Toulouse ; it is one of the earliest examples of early Germanic law. The compilation itself was the work of Leo, a Roman lawyer and principal counsellor of the king. The customs of the Visigothic nation were recognised and affirmed. The Code is largely confused and it appears that it was merely a recollection of Gothic custom altered by Roman law.

An antiphonary or antiphonal is one of the liturgical books intended for use in choro, and originally characterized, as its name implies, by the assignment to it principally of the antiphons used in various parts of the Latin liturgical rites.

The Aquileian Rite was a particular liturgical tradition of the Patriarchate of Aquileia and hence called the ritus patriarchinus. It was effectively replaced by the Roman Rite by the beginning of the seventeenth century, although elements of it survived in St. Mark's Basilica in Venice until 1807.

The Lex Burgundionum refers to the law code of the Burgundians, probably issued by king Gundobad. It is influenced by Roman law and deals with domestic laws concerning marriage and inheritance as well as regulating weregild and other penalties. Interaction between Burgundians is treated separately from interaction between Burgundians and Gallo-Romans. The oldest of the 14 surviving manuscripts of the text dates to the 9th century, but the code's institution is ascribed to king Gundobad, with a possible revision by his successor Sigismund. The Lex Romana Burgundionum is a separate code, containing various laws taken from Roman sources, probably intended to apply to the Burgundians' Gallo-Roman subjects. The oldest copy of this text dates to the 7th century.

The Codex Gregorianus is the title of a collection of constitutions of Roman emperors over a century and a half from the 130s to 290s AD. It is believed to have been produced around 291–294 but the exact date is unknown.

The Codex Hermogenianus is the title of a collection of constitutions of the Roman emperors of the first tetrarchy, mostly from the years 293–94. Most of the work is now lost. The work became a standard reference in late antiquity, until it was superseded by the Breviary of Alaric and the Codex Justinianeus.

The Romansh people are a Romance ethnic group, the speakers of the Romansh language, native to the Swiss canton of Grisons (Graubünden).

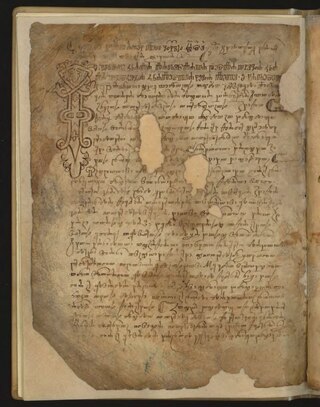

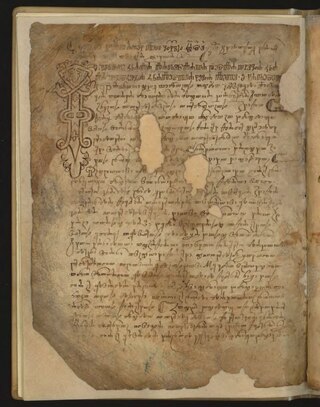

Law code of Vinodol or Vinodol statute is one of the oldest law texts written in the Chakavian dialect of Croatian and is among the oldest Slavic codes. It was written in the Glagolitic alphabet. It was originally compiled in 1288 by a commission of 42 members in Novi Vinodolski, a town on the Adriatic Sea coast in Croatia, located south of Crikvenica, Selce and Bribir and north of Senj. However, the code itself is preserved in a 16th-century copy.

Germanic law is a scholarly term used to describe a series of commonalities between the various law codes of the early Germanic peoples. These were compared with statements in Tacitus and Caesar as well as with high and late medieval law codes from Germany and Scandinavia. Until the 1950s, these commonalities were held to be the result of a distinct Germanic legal culture. Scholarship since then has questioned this premise and argued that many "Germanic" features instead derive from provincial Roman law. Although most scholars no longer hold that Germanic law was a distinct legal system, some still argue for the retention of the term and for the potential that some aspects of the Leges in particular derive from a Germanic culture. Scholarly consensus as of 2023 is that Germanic law is best understood in opposition to Roman law, in that it was not "learned" and incorporated regional pecularities.

The Institutes is a beginners' textbook on Roman private law written around 161 CE by the classical Roman jurist Gaius. The Institutes are considered to be "by far the most influential elementary-systematic presentation of Roman private law in late antiquity, the Middle Ages and modern times". The content of the textbook was considered to be lost until 1816, when a manuscript of it − probably of the 5th century − was discovered.

The Asega-bôk, English: "Book of the Judges", was part of the legal code for the Rustringian Frisians. The oldest known manuscript version, the First Riustring Manuscript is, besides the oldest extant text in Frisian, one of the oldest remaining continental codes of Germanic law.

Raetia Curiensis was an early medieval province in Central Europe, named after the preceding Roman province of Raetia prima which retained its Romansh culture during the Migration Period, while the adjacent territories in the north were largely settled by Alemannic tribes. The administrative capital was Chur in the present Swiss canton of Grisons.

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 4404 is a medieval manuscript from the 9th century containing, among other legal texts, the Breviary of Alaric, and is notable also for containing illustrations of rulers.

The Fragmenta Vaticana are the fragments of an anonymous Latin work on Roman law written in the 4th century AD. Their importance to scholars stems from their being untouched by the Justinianic reforms of the 6th century.

Ewa ad Amorem, traditionally known as the Lex Francorum Chamavorum, is a 9th-century law code from the Carolingian Empire. It is generally counted among the leges barbarorum, but it was not a national law. It applied only to a certain region in the Low Countries, although exactly where is disputed. Its association with the Chamavi is a modern conjecture.

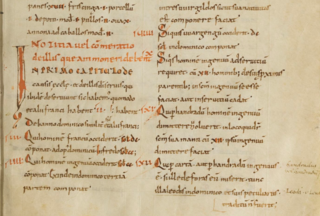

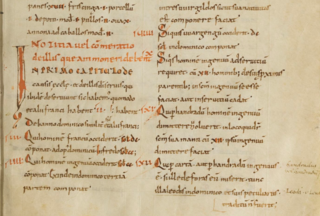

![Page where the Lex Romana Curiensis begins in the Verona manuscript. The beginning of the text is in the middle of the right column: In nomine s[an]c[t]ae Trinitatis incipiunt capitula libri primi legis (In the name of the Holy Trinity, the chapters of the first book of the law begin...). Lex Romana Utinensis.png](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/31/Lex_Romana_Utinensis.png/170px-Lex_Romana_Utinensis.png)