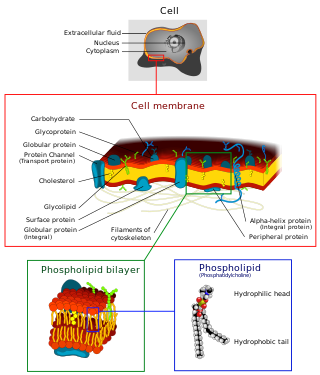

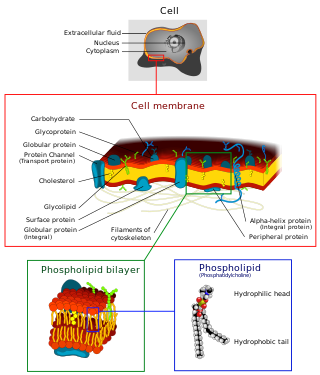

A biological membrane, biomembrane or cell membrane is a selectively permeable membrane that separates the interior of a cell from the external environment or creates intracellular compartments by serving as a boundary between one part of the cell and another. Biological membranes, in the form of eukaryotic cell membranes, consist of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded, integral and peripheral proteins used in communication and transportation of chemicals and ions. The bulk of lipids in a cell membrane provides a fluid matrix for proteins to rotate and laterally diffuse for physiological functioning. Proteins are adapted to high membrane fluidity environment of the lipid bilayer with the presence of an annular lipid shell, consisting of lipid molecules bound tightly to the surface of integral membrane proteins. The cell membranes are different from the isolating tissues formed by layers of cells, such as mucous membranes, basement membranes, and serous membranes.

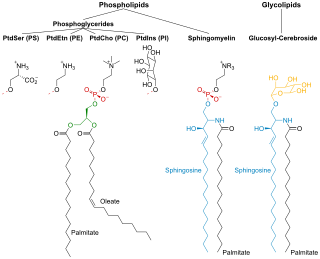

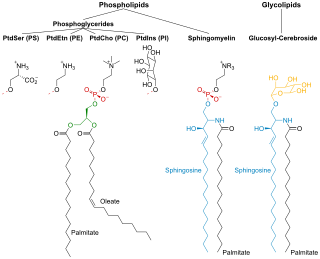

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue. Marine phospholipids typically have omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA integrated as part of the phospholipid molecule. The phosphate group can be modified with simple organic molecules such as choline, ethanolamine or serine.

The lipid bilayer is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, proteins and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble (hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps.

A micelle or micella is an aggregate of surfactant amphipathic lipid molecules dispersed in a liquid, forming a colloidal suspension. A typical micelle in water forms an aggregate with the hydrophilic "head" regions in contact with surrounding solvent, sequestering the hydrophobic single-tail regions in the micelle centre.

Lipophilicity is the ability of a chemical compound to dissolve in fats, oils, lipids, and non-polar solvents such as hexane or toluene. Such compounds are called lipophilic. Such non-polar solvents are themselves lipophilic, and the adage "like dissolves like" generally holds true. Thus lipophilic substances tend to dissolve in other lipophilic substances, whereas hydrophilic ("water-loving") substances tend to dissolve in water and other hydrophilic substances.

A liposome is a small artificial vesicle, spherical in shape, having at least one lipid bilayer. Due to their hydrophobicity and/or hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, particle size and many other properties, liposomes can be used as drug delivery vehicles for administration of pharmaceutical drugs and nutrients, such as lipid nanoparticles in mRNA vaccines, and DNA vaccines. Liposomes can be prepared by disrupting biological membranes.

In chemistry, an amphiphile, or amphipath, is a chemical compound possessing both hydrophilic and lipophilic properties. Such a compound is called amphiphilic or amphipathic. Amphiphilic compounds include surfactants and detergents. The phospholipid amphiphiles are the major structural component of cell membranes.

A lamella in biology refers to a thin layer, membrane or plate of tissue. This is a very broad definition, and can refer to many different structures. Any thin layer of organic tissue can be called a lamella and there is a wide array of functions an individual layer can serve. For example, an intercellular lipid lamella is formed when lamellar disks fuse to form a lamellar sheet. It is believed that these disks are formed from vesicles, giving the lamellar sheet a lipid bilayer that plays a role in water diffusion.

Surfactin is a cyclic lipopeptide, commonly used as an antibiotic for its capacity as a surfactant. It is an amphiphile capable of withstanding hydrophilic and hydrophobic environments. The Gram-positive bacterial species Bacillus subtilis produces surfactin for its antibiotic effects against competitors. Surfactin showcases antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and hemolytic effects.

Membrane lipids are a group of compounds which form the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. The three major classes of membrane lipids are phospholipids, glycolipids, and cholesterol. Lipids are amphiphilic: they have one end that is soluble in water ('polar') and an ending that is soluble in fat ('nonpolar'). By forming a double layer with the polar ends pointing outwards and the nonpolar ends pointing inwards membrane lipids can form a 'lipid bilayer' which keeps the watery interior of the cell separate from the watery exterior. The arrangements of lipids and various proteins, acting as receptors and channel pores in the membrane, control the entry and exit of other molecules and ions as part of the cell's metabolism. In order to perform physiological functions, membrane proteins are facilitated to rotate and diffuse laterally in two dimensional expanse of lipid bilayer by the presence of a shell of lipids closely attached to protein surface, called annular lipid shell.

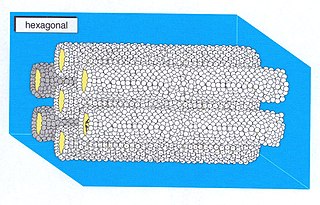

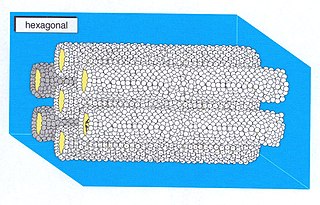

A hexagonal phase of lyotropic liquid crystal is formed by some amphiphilic molecules when they are mixed with water or another polar solvent. In this phase, the amphiphile molecules are aggregated into cylindrical structures of indefinite length and these cylindrical aggregates are disposed on a hexagonal lattice, giving the phase long-range orientational order.

Lyotropic liquid crystals result when amphiphiles, which are both hydrophobic and hydrophilic, dissolve into a solution that behaves both like a liquid and a solid crystal. This liquid crystalline mesophase includes everyday mixtures like soap and water.

In colloidal chemistry, one property of a lipid bilayer is the relative mobility (fluidity) of the individual lipid molecules and how this mobility changes with temperature. This response is known as the phase behavior of the bilayer. Broadly, at a given temperature a lipid bilayer can exist in either a liquid or a solid phase. The solid phase is commonly referred to as a “gel” phase. All lipids have a characteristic temperature at which they undergo a transition (melt) from the gel to liquid phase. In both phases the lipid molecules are constrained to the two dimensional plane of the membrane, but in liquid phase bilayers the molecules diffuse freely within this plane. Thus, in a liquid bilayer a given lipid will rapidly exchange locations with its neighbor millions of times a second and will, through the process of a random walk, migrate over long distances.

In membrane biology, fusion is the process by which two initially distinct lipid bilayers merge their hydrophobic cores, resulting in one interconnected structure. If this fusion proceeds completely through both leaflets of both bilayers, an aqueous bridge is formed and the internal contents of the two structures can mix. Alternatively, if only one leaflet from each bilayer is involved in the fusion process, the bilayers are said to be hemifused. In hemifusion, the lipid constituents of the outer leaflet of the two bilayers can mix, but the inner leaflets remain distinct. The aqueous contents enclosed by each bilayer also remain separated.

A model lipid bilayer is any bilayer assembled in vitro, as opposed to the bilayer of natural cell membranes or covering various sub-cellular structures like the nucleus. They are used to study the fundamental properties of biological membranes in a simplified and well-controlled environment, and increasingly in bottom-up synthetic biology for the construction of artificial cells. A model bilayer can be made with either synthetic or natural lipids. The simplest model systems contain only a single pure synthetic lipid. More physiologically relevant model bilayers can be made with mixtures of several synthetic or natural lipids.

The presence of ethanol can lead to the formations of non-lamellar phases also known as non-bilayer phases. Ethanol has been recognized as being an excellent solvent in an aqueous solution for inducing non-lamellar phases in phospholipids. The formation of non-lamellar phases in phospholipids is not completely understood, but it is significant that this amphiphilic molecule is capable of doing so. The formation of non-lamellar phases is significant in biomedical studies which include drug delivery, the transport of polar and non-polar ions using solvents capable of penetrating the biomembrane, increasing the elasticity of the biomembrane when it is being disrupted by unwanted substances and functioning as a channel or transporter of biomaterial.

The cell membrane is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment. The cell membrane consists of a lipid bilayer, made up of two layers of phospholipids with cholesterols interspersed between them, maintaining appropriate membrane fluidity at various temperatures. The membrane also contains membrane proteins, including integral proteins that span the membrane and serve as membrane transporters, and peripheral proteins that loosely attach to the outer (peripheral) side of the cell membrane, acting as enzymes to facilitate interaction with the cell's environment. Glycolipids embedded in the outer lipid layer serve a similar purpose.

In colloidal chemistry, the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of a surfactant is one of the parameters in the Gibbs free energy of micellization. The concentration at which the monomeric surfactants self-assemble into thermodynamically stable aggregates is the CMC. The Krafft temperature of a surfactant is the lowest temperature required for micellization to take place. There are many parameters that affect the CMC. The interaction between the hydrophilic heads and the hydrophobic tails play a part, as well as the concentration of salt within the solution and surfactants.

A unilamellar liposome is a spherical liposome, a vesicle, bounded by a single bilayer of an amphiphilic lipid or a mixture of such lipids, containing aqueous solution inside the chamber. Unilamellar liposomes are used to study biological systems and to mimic cell membranes, and are classified into three groups based on their size: small unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (SUVs) that with a size range of 20–100 nm, large unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (LUVs) with a size range of 100–1000 nm and giant unilamellar liposomes/vesicles (GUVs) with a size range of 1–200 μm. GUVs are mostly used as models for biological membranes in research work. Animal cells are 10–30 μm and plant cells are typically 10–100 μm. Even smaller cell organelles such as mitochondria are typically 1–2 μm. Therefore, a proper model should account for the size of the specimen being studied. In addition, the size of vesicles dictates their membrane curvature which is an important factor in studying fusion proteins. SUVs have a higher membrane curvature and vesicles with high membrane curvature can promote membrane fusion faster than vesicles with lower membrane curvature such as GUVs.

Lamellar phase refers generally to packing of polar-headed, long chain, nonpolar-tailed molecules (amphiphiles) in an environment of bulk polar liquid, as sheets of bilayers separated by bulk liquid. In biophysics, polar lipids pack as a liquid crystalline bilayer, with hydrophobic fatty acyl long chains directed inwardly and polar headgroups of lipids aligned on the outside in contact with water, as a 2-dimensional flat sheet surface. Under transmission electron microscopy (TEM), after staining with polar headgroup reactive chemical osmium tetroxide, lamellar lipid phase appears as two thin parallel dark staining lines/sheets, constituted by aligned polar headgroups of lipids. 'Sandwiched' between these two parallel lines, there exists one thicker line/sheet of non-staining closely packed layer of long lipid fatty acyl chains. This TEM-appearance became famous as Robertson's unit membrane - the basis of all biological membranes, and structure of lipid bilayer in unilamellar liposomes. In multilamellar liposomes, many such lipid bilayer sheets are layered concentrically with water layers in between.