| Image | Date | Unit | Colour | Battle | War | Captured by | Notes | Ref |

|---|

| 14 August 1756 | 50th Regiment of Foot (American Provincials) | King's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Fort Oswego | Seven Years' War | France | These two units were ranked as regular regiments of foot but consisted of raw recruits from the colonies. They were disbanded shortly after the surrender at Fort Oswego. Two of these colours were recovered by British forces during the September 1760 capture of Montreal. | [23] |

| 51st Regiment of Foot (Cape Breton Regiment) | King's colour and regimental colour | [23] |

| 15 October 1760 | Unknown regiment | Unknown colour | Battle of Kloster Kampen | Seven Years' War | France | | [24] |

| 20 October 1775 | 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers) | Regimental colour | Surrender of Fort Chamblé | American War of Independence | Thirteen Colonies | Only one company of the regiment was present at this action | [25] [26] [23] |

Surrender of colours at Saratoga Surrender of colours at Saratoga | 17 October 1777 | 37th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Surrender at Saratoga | American War of Independence | United States of America | Other regiments, including the 9th and 62nd Regiments of Foot, successfully concealed their colours and returned them to Britain. Other colours were sent in the personal baggage of General John Burgoyne. | [27] [28] [29] [30] |

| 1777-8 | 81st Regiment of Foot (Aberdeenshire Highland Regiment) | King's colour and regimental colour | At sea between Britain and Ireland | American War of Independence | United States of America | Captured by a privateer, possibly John Paul Jones | [27] |

| 16 July 1779 | 17th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Stony Point | American War of Independence | United States of America | | [31] |

| 21 September 1779 | 16th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Baton Rouge | American War of Independence | Spain | | [27] |

The King's colour of the 7th Regiment is now exhibited at the West Point Museum | 17 January 1781 | 7th Regiment of Foot | King's colour | Battle of Cowpens | American War of Independence | United States of America | | [25] |

| 8 September 1781 | 64th Regiment of Foot | King's colour (possible) | Battle of Eutaw Springs | American War of Independence | United States of America | The 64th Regiment returned from America without its King's colour, it was possibly lost when it was driven back at the Battle of Eutaw Springs | [32] |

A depiction of British colours (left) during the surrender at Yorktown | 19 October 1781 | 43rd Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour (possible) | Surrender at Yorktown | American War of Independence | United States of America,

France | The 43rd Regiment later claimed its colours weren't lost and had been left at the depot in New York. The 23rd Foot (Royal Welsh Fuzileers) and 33rd Regiment of Foot also surrendered at Yorktown but are believed to have hidden their colours beforehand. In addition to the British regiments 18 colours were captured from Hessian, Ansbach and Bayreuth units. | [25] [33] |

| 19 October 1781 | 76th Regiment of Foot (MacDonald's Highlanders) | King's colour and regimental colour |

| 19 October 1781 | 80th Regiment of Foot (Royal Edinburgh Volunteers) | King's colour and regimental colour |

| 26/27 November 1781 | 15th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | French capture of Sint Eustatius | Anglo-French War (1778–1783) | France | | [34] |

| 13th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [34] |

| 3 May 1783 | 98th Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Siege of Bednore | Second Anglo-Mysore War | Mysore,

France | | [34] |

| 100th Regiment of Foot (Loyal Lincolnshire Regiment) | King's colour and regimental colour | [34] |

| 102nd Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [34] |

| 1794 | 43rd (Monmouthshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | Invasion of Guadeloupe | War of the First Coalition | France | | [35] |

| 65th (2nd Yorkshire, North Riding) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | [35] |

| King's colour (left) and regimental colour (right) | 11 August 1806 | 2nd battalion, 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot (MacLeod's Highlanders) | King's colour and regimental colour | First British occupation of Buenos Aires | Anglo-Spanish War (1796–1808) | Spain | | [36] [35] |

The Buffs defend their colours at Albuera | 16 May 1811 | 1st battalion, 3rd Regiment of Foot, "The Buffs" | Part of the regimental colour (staff, cords and part of flag lost, later recovered in counterattack) | Battle of Albuera | Peninsular War | France | The regimental colour was lost to a French attack but most of the flag was recovered in a counterattack by the 7th Regiment of Foot | [36] [37] |

| 2nd battalion, 48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | | [36] |

| 2nd battalion, 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour | | [36] |

| 22 July 1812 | 2nd battalion, 53rd (Shropshire) Regiment of Foot | Part of the King's colour (staff and some of the flag lost) | Battle of Salamanca | Peninsular War | France | | [36] |

Two of the colours during the Siege of Bergen op Zoom | 8 March 1814 | 2nd battalion, 1st Regiment of Foot Guards | Unknown | Siege of Bergen op Zoom | War of the Sixth Coalition | France | Source just states "colours" lost. The Foot Guards of this period carried three king's colours: the colonel's, lieutenant-colonel's and major's colours. Unlike the king's colours of line regiments these had plain crimson fields. Each company also had a colour which was the union flag defaced with a badge, the 1st Foot Guards had 24 of these, one of which was carried in rotation as the regimental colour. | [36] [38] |

| 4th battalion, 1st (Royal) Regiment of Foot | King's colour and regimental colour | The colours were weighted and thrown into the River Zoom by the regiment's adjutant in an attempt to save them from capture but were afterwards recovered by the French. | [36] [39] |

| 2nd battalion, 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot | Regimental colour | | [36] |

| 16 June 1815 | 2nd battalion, 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot | King's colour | Battle of Quatre Bras | Hundred Days | France | The colour came into the possession of General François-Xavier Donzelot who commanded the 2nd Infantry Division during the battle. It was inherited by his grandson who gave them away in payment for a debt. In 1909 the colour was sold to a British captain on holiday and returned to the regimental museum. The colour is now in the collection of the Regimental Museum of The Royal Welsh. | [36] [40] |

King's colour carried by battalions of the King's German Legion | 18 June 1815 | 5th Kings German Legion Line Battalion | King's colour | Battle of Waterloo | War of the Seventh Coalition | France | | [36] |

| 8th Kings German Legion Line Battalion | King's colour | | [36] |

The last stand of the 44th, the regimental colour is shown wrapped around Souter's waist | 13 January 1842 | 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour and regimental colour | Last stand at Jugdulluk | First Anglo-Afghan War | Afghanistan | Knowing they would be overrun by the Afghan forces Captain Souter and Lieutenant Cumberland took the colours from their staffs and tried to wrap them around their bodies. Cumberland was unable to button his coat over the queen's colour and handed it to Colour-Sergeant Carey who hid it under his sheepskin coat. Carey was killed and the colour lost, but Souter was captured by the Afghans who thought him worthy of ransom after mistaking the bright yellow colour for expensive clothing. Souter brought the regimental colour back with him when he was released some months later. | [41] [42] [43] |

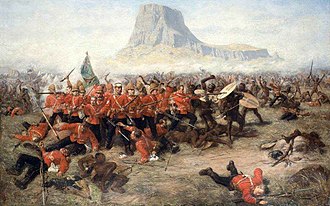

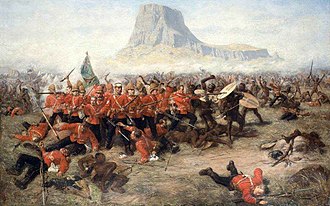

The 24th advance at Chillianwala | 13 January 1849 | 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour | Battle of Chillianwala | Second Anglo-Sikh War | Sikh Empire | The colour was separated from its staff and carried by the wounded Private Battlestone during the retreat. Having refused to give up the colours to his comrades Battlestone fell dead, unnoticed. The colour was not found by the British the following morning; as it was not paraded by the Sikhs as a trophy it was perhaps taken by local villagers or camp followers. The battle was among the worst on record for losses of British colours, with nine from the British Indian units also lost. | [44] [45] [46] |

A depiction of a last stand around the regimental colour of the 2nd battalion, though there is no evidence that the colours were unfurled during the battle. | 22 January 1879 | 24th (The 2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Isandlwana | Anglo-Zulu War | Zulu Kingdom | Both colours of the 2nd battalion were lost on the battlefield, though part of one pole and a crown finial were recovered separately later.The queen's colour of the 1st battalion was also present at the battle; it was brought away by Lieutenants Melville and Coghill who were killed in their attempted flight. The colour was found in the Buffalo River by British forces on 4 February, near to where they died. | [47] |

| 27 July 1880 | 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot | Queen's colour and regimental colour | Battle of Maiwand | Second Anglo-Afghan War | Afghanistan | This was the last loss of British colours. | [48] |