Related Research Articles

Arabic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy based on the Arabic alphabet. It is known in Arabic as khatt, derived from the word 'line', 'design', or 'construction'. Kufic is the oldest form of the Arabic script.

Fatima, also spelled Fatimah, is a female given name of Arabic origin used throughout the Muslim world. Several relatives of the Islamic prophet Muhammad had the name, including his daughter Fatima as the most famous one. The literal meaning of the name is one who weans an infant or one who abstains.

Al-Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib was a paternal uncle and Sahabi (companion) of Muhammad, just three years older than his nephew. A wealthy merchant, during the early years of Islam he protected Muhammad while he was in Mecca, but only became a convert after the Battle of Badr in 624 CE (2 AH). His descendants founded the Abbasid dynasty in 750.

Nastaliq, also romanized as Nastaʿlīq, is one of the main calligraphic hands used to write the Perso-Arabic script in the Persian and Urdu languages, often used also for Ottoman Turkish poetry, rarely for Arabic. Nastaliq developed in Iran from naskh beginning in the 13th century and remains very widely used in Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan and as a minority script in India and other countries for written poetry and as a form of art.

Islamic calligraphy is the artistic practice of handwriting and calligraphy, in the languages which use Arabic alphabet or the alphabets derived from it. It includes Arabic, Persian, Ottoman, and Urdu calligraphy. It is known in Arabic as khatt Arabi, which translates into Arabic line, design, or construction.

Sheikh Hamdullah (1436–1520), born in Amasya, Ottoman Empire, was a master of Islamic calligraphy.

Jaʽfar, meaning in Arabic "small stream/rivulet/creek", is a masculine Arabic given name, common among Muslims especially Shia.

Jordanian art has a very ancient history. Some of the earliest figurines, found at Aïn Ghazal, near Amman, have been dated to the Neolithic period. A distinct Jordanian aesthetic in art and architecture emerged as part of a broader Islamic art tradition which flourished from the 7th-century. Traditional art and craft is vested in material culture including mosaics, ceramics, weaving, silver work, music, glass-blowing and calligraphy. The rise of colonialism in North Africa and the Middle East, led to a dilution of traditional aesthetics. In the early 20th-century, following the creation of the independent nation of Jordan, a contemporary Jordanian art movement emerged and began to search for a distinctly Jordanian art aesthetic that combined both tradition and contemporary art forms.

Musaddak Jameel Al-Habeeb is an Iraqi American contemporary calligrapher who follows the original traditions in Arabic-Islamic calligraphy. He is self-taught, and never studied under any master calligrapher, according to the traditional norm.

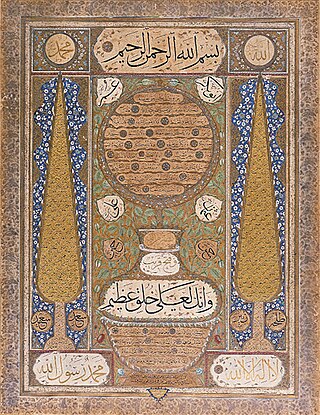

Turkish or Ottoman illumination covers non-figurative painted or drawn decorative art in books or on sheets in muraqqa or albums, as opposed to the figurative images of the Ottoman miniature. In Turkish it is called “tezhip”, meaning “ornamenting with gold”. It was a part of the Ottoman Book Arts together with the Ottoman miniature (taswir), calligraphy (hat), bookbinding (cilt) and paper marbling (ebru). In the Ottoman Empire, illuminated and illustrated manuscripts were commissioned by the Sultan or the administrators of the court. In Topkapi Palace, these manuscripts were created by the artists working in Nakkashane, the atelier of the miniature and illumination artists. Both religious and non-religious books could be illuminated. Also sheets for albums levha consisted of illuminated calligraphy (hat) of tughra, religious texts, verses from poems or proverbs, and purely decorative drawings.

Yaqut al-Musta'simi (Arabic: ياقوت المستعصمي) was a well-known calligrapher and secretary of the last Abbasid caliph.

The term hilya denotes both a visual form in Ottoman art and a religious genre of Ottoman Turkish literature, each dealing with the physical description of Muhammad. Hilya literally means "ornament".

Al-Shifāʾ bint ʿAbd Allāh, whose given name was Laylā, was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

ʿArīb al-Ma’mūnīya was a qayna of the early Abbasid period, who has been characterised as 'the most famous slave singer to have ever resided at the Baghdad court'. She lived to 96, and her career spanned the courts of five caliphs.

The Hurufiyya movement is an aesthetic movement that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century amongst Muslim artists, who used their understanding of traditional Islamic calligraphy within the precepts of modern art. By combining tradition and modernity, these artists worked towards developing a culture specific visual language, which instilled a sense of national identity in their respective nation states, at a time when many of these states where shaking off colonial rule and asserting their independence. They adopted the same name as the Hurufi, an approach of Sufism which emerged in the late 14th–early 15th century. Art historian Sandra Dagher has described Hurufiyya as the most important movement to emerge in Arabic art in the 20th century.

Qiyān were a social class of women, trained as entertainers, which existed in the pre-modern Islamic world. The term has been used for both non-free women and free, including some of which came from the nobility. It has been suggested that "the geisha of Japan are perhaps the most comparable form of socially institutionalized female companionship and entertainment for male patrons, although, of course, the differences are also myriad".

Hashem Muhammad al-Baghdadi (1917–1973) was an Iraqi master calligrapher, noted for his lettering which exhibited a steadiness of hand and fluidity of movement. In his later life, he was acknowledged as the "imam of calligraphy" across the Arab world, and would be the last of the classical calligraphers. He also authored several important texts on the art of calligraphy.

Esmâ Ibret Hanim was an Ottoman calligrapher and poet, noted as the most successful female calligrapher of her day.

Şerife Fatma "Mevhibe" Hanım was a 19th century female Ottoman calligrapher and poet.

Nuria Garcia Masip is a Spanish calligrapher of Arabic calligraphy. She started to learn Arabic calligraphy when she visited Morocco. In 2000, she learned Arabic calligraphy under the tutelage of calligrapher Mohamed Zakariya. Her interest in calligraphy took her to Istanbul, where she learned the various scripts and styles of Arabic calligraphy from Hasan Çelebi and Davut Bektaş. In 2007, she received a certificate in the Thuluth and Naskh scripts.

References

- ↑ Al-Munajjid, S.A.D., "Women's Roles in the Art of Arabic Calligraphy" in: George Nicholas Atiyeh (ed.), The Book in the Islamic World: The Written Word and Communication in the Middle East, Albany, State University of New York Press, 1995, p. 146

- ↑ Sayeed, A., Women and the Transmission of Religious Knowledge in Islam, Cambridge University Press, 2013, pp 70-71

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Kazan, H., Dünden Bugüne Hanım Hattatlar (Female Calligraphers Past And Present), Istanbul, Büyükşehir Belediyesi, 2010, Chapter 5

- 1 2 3 Momin, A.R., "The Calligraphic World of Nuria Garcia Masip", IOS Minaret, Vol. 10, No. 8, 1–15 September 2015 Online:

- ↑ Kazan, H., Dünden Bugüne Hanim Hattatlar [Female calligraphers past and present], Istanbul, Büyüksehir Belediyesi Kültür Isleri Daire Baskanligi, 2010, ISBN 6055592517

- ↑ Adams Helminski, C., Women of Sufism: A Hidden Treasure, Shambhala Publications, 2003, [E-book edition], n.p.

- ↑ Al-Munajjid, S.A.D., "Women's Roles in the Art of Arabic Calligraphy" in: George Nicholas Atiyeh (ed.), The Book in the Islamic World: The Written Word and Communication in the Middle East, Albany, State University of New York Press, 1995, p. 146

- ↑ Dervisevic, H., "18th-century Qur'an Transcribed by a Woman," Islamic Arts Magazine, 1 June 2017,

- ↑ Kazan H., "XIX. Asırda Bir Kadın Hattat: Şerife Zehra Hanım", Toplumsal Tarih, 2014, pp 86-90

- ↑ Türkischer Biographischer Index [Turkish Biographical Index], De Gruyter, 2011, p. 1087

- ↑ Muslim Heritage, Online:

- ↑ Islamic Arts Portal, Online (in Turkish and English)

- ↑ Al-Munajjid, S.A.D., "Women's Roles in the Art of Arabic Calligraphy" in: George Nicholas Atiyeh (ed.), The Book in the Islamic World: The Written Word and Communication in the Middle East, Albany, State University of New York Press, 1995, pp 146-147

- ↑ Schick, T.C., M. Uğur Derman 65th birthday Festschrift Sabancı Universitesi, 2000, p. 347