Ammonius Hermiae was a Greek philosopher from Alexandria in the eastern Roman empire during Late Antiquity. A Neoplatonist, he was the son of the philosophers Hermias and Aedesia, the brother of Heliodorus of Alexandria and the grandson of Syrianus. Ammonius was a pupil of Proclus in Roman Athens, and taught at Alexandria for most of his life, having obtained a public chair in the 470s.

The problem of universals is an ancient question from metaphysics that has inspired a range of philosophical topics and disputes: Should the properties an object has in common with other objects, such as color and shape, be considered to exist beyond those objects? And if a property exists separately from objects, what is the nature of that existence?

A syllogism is a kind of logical argument that applies deductive reasoning to arrive at a conclusion based on two propositions that are asserted or assumed to be true.

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius, was a Roman senator, consul, magister officiorum, historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the translation of the Greek classics into Latin, a precursor to the Scholastic movement, and, along with Cassiodorus, one of the two leading Christian scholars of the 6th century. The local cult of Boethius in the Diocese of Pavia was sanctioned by the Sacred Congregation of Rites in 1883, confirming the diocese's custom of honouring him on the 23 October.

The Organon is the standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logical analysis and dialectic. The name Organon was given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics, who maintained against the Stoics that Logic was "an instrument" of Philosophy.

The Basilica of Saint Sabina is a historic church on the Aventine Hill in Rome, Italy. It is a titular minor basilica and mother church of the Roman Catholic Order of Preachers, better known as the Dominicans.

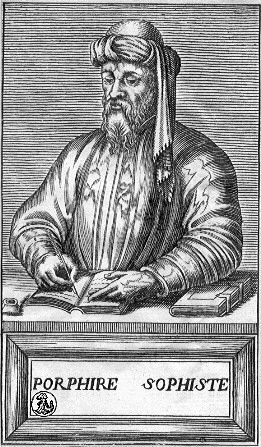

Porphyry of Tyre was a Neoplatonic philosopher born in Tyre, Roman Phoenicia during Roman rule. He edited and published The Enneads, the only collection of the work of Plotinus, his teacher.

Albert of Saxony was a German philosopher and mathematician known for his contributions to logic and physics. He was bishop of Halberstadt from 1366 until his death.

Gilbert de la Porrée, also known as Gilbert of Poitiers, Gilbertus Porretanus or Pictaviensis, was a scholastic logician and theologian and Bishop of Poitiers.

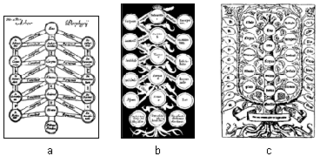

The Porphyrian tree or Tree of Porphyry is a classic device for illustrating a "scale of being", attributed to the 3rd century CE Greek neoplatonist philosopher and logician Porphyry, and revived through the translations of Boethius.

James of Venice was a Catholic cleric and significant translator of Aristotle of the twelfth century. He has been called "the first systematic translator of Aristotle since Boethius." Not much is otherwise known about him.

The transmission of the Greek Classics to Latin Western Europe during the Middle Ages was a key factor in the development of intellectual life in Western Europe. Interest in Greek texts and their availability was scarce in the Latin West during the Early Middle Ages, but as traffic to the East increased, so did Western scholarship.

The Isagoge or "Introduction" to Aristotle's "Categories", written by Porphyry in Greek and translated into Latin by Boethius, was the standard textbook on logic for at least a millennium after his death. It was composed by Porphyry in Sicily during the years 268–270, and sent to Chrysaorium, according to all the ancient commentators Ammonius, Elias, and David. The work includes the highly influential hierarchical classification of genera and species from substance in general down to individuals, known as the Tree of Porphyry, and an introduction which mentions the problem of universals.

Topical logic is the logic of topical argument, a branch of rhetoric developed in the Late Antique period from earlier works, such as Aristotle's Topics and Cicero's Topica. It consists of heuristics for developing arguments, which are in the first place plausible rather than rigorous, from commonplaces. In other words, therefore, it consists of standardized ways of thinking up debating techniques from existing, thought-through positions. The actual practice of topical argument was much developed by Roman lawyers. Cicero took the theory of Aristotle to be an aspect of rhetoric. As such it belongs to inventio in the classic fivefold division of rhetoric.

Patrick Osmund Lewry (1929–1987) was an English Dominican who made significant contributions to the history of logic and the philosophy of language in the thirteenth century. Lewry studied mathematical logic under Lejewski and A.N. Prior at Manchester (1961–2). From 1962–7 he taught the philosophy of language and logic at Hawkesyard. He was assigned to the Oxford Blackfriars in 1967. Dissatisfaction with teaching led him to work for an Oxford D.Phil. on the logic teaching of Robert Kilwardby. In 1979 he began the study of the history of grammar, logic and rhetoric at Oxford in the period 1220–1320. In 1979 he went to the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies in Toronto first as a research associate, then as a senior fellow. He died on 23 April 1987 at the age of 57 at the Oxford Dominican House.

David was a Greek scholar and a commentator on Aristotle and Porphyry.

Elias was a Greek scholar and a commentator on Aristotle and Porphyry.

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning.

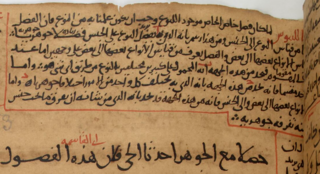

Allīnūs or Alīnūs was an Alexandrian philosopher and commentator on Aristotle from the sixth or seventh century AD. He wrote in Greek, but is known only from Arabic sources, including some translated excerpts of his works.

The Liber sex principiorum is an anonymous Latin work of philosophy from the late twelfth century. It aims to complement Aristotle's Categories by providing justifications for the six categories neglected by Aristotle in his scheme of ten categories. The "six principles" (categories) of the title are place, time, position, possession, action and passion. The Liber became one of the standard works of the logica vetus curriculum and by the mid-thirteenth century was erroneously ascribed to Gilbert de la Porrée. It was widely commented upon by medieval philosophers, including Robert Kilwardby, Nicholas of Paris, Martin of Dacia, Radulphus Brito, Peter of Auvergne and Thomas of Erfurt. Nevertheless, the complete text does not survive, only fragments.