The Spanish missions in California comprise a series of 21 religious outposts or missions established between 1769 and 1833 in what is now the U.S. state of California. Founded by Catholic priests of the Franciscan order to evangelize the Native Americans, the missions led to the creation of the New Spain province of Alta California and were part of the expansion of the Spanish Empire into the most northern and western parts of Spanish North America.

Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa is a Spanish mission founded September 1, 1772 by Father Junípero Serra in San Luis Obispo, California. Named after Saint Louis of Anjou, the bishop of Toulouse, the mission is the namesake of San Luis Obispo. The mission offers public tours of the church and grounds.

Mission San Buenaventura, formally known as the Mission Basilica of San Buenaventura, is a Catholic parish and basilica in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. The parish church in the city of Ventura, California, United States, is a Spanish mission founded by the Order of Friars Minor. Founded on March 31, 1782, it was the ninth Spanish mission established in Alta California and the last to be established by the head of the Franciscan missions in California, Junípero Serra. Designated a California Historical Landmark, the mission is one of many locally designated landmarks in downtown Ventura.

Mission San Fernando Rey de España is a Spanish mission in the Mission Hills community of Los Angeles, California. The mission was founded on 8 September 1797, and was the seventeenth of the twenty-one Spanish missions established in Alta California. Named for Saint Ferdinand, the mission is the namesake of the nearby city of San Fernando and the San Fernando Valley.

Ventura County is a county in the southern part of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 843,843. The largest city is Oxnard, and the county seat is the city of Ventura.

The Santa Clara River Valley is a rural, mainly agricultural, valley in Ventura County, California that has been given the moniker Heritage Valley by the namesake tourism bureau. The valley includes the communities of Santa Paula, Fillmore, Piru and the national historic landmark of Rancho Camulos. Named for the Santa Clara River, which winds through the valley before emptying into the Pacific Ocean between the cities of Ventura and Oxnard, the tourist bureau describes it as ".... Southern California's last pristine agricultural valley nestled along the banks of the free-flowing Santa Clara River."

Francisco Hermenegildo Tomás GarcésO.F.M. was a Spanish Franciscan friar who served as a missionary and explorer in the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain. He explored much of the southwestern region of North America, including present day Sonora and Baja California in Mexico, and the U.S. states of Arizona and California. He was killed along with his companion friars during an uprising by the Native American population, and they have been declared martyrs for the faith by the Catholic Church. The cause for his canonization was opened by the Church.

José Francisco Ortega was an indigenous Californio soldier and early settler of Alta California. A member of the Portolá expedition in 1769, Ortega stayed on to become the patriarch of an important Californio family.

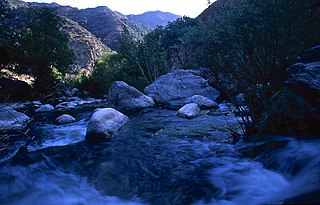

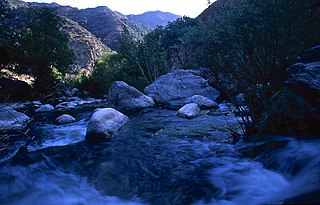

Piru Creek is a major stream, about 71 miles (114 km) long, in northern Los Angeles County and eastern Ventura County, California. It is a tributary of the Santa Clara River, the largest stream system in Southern California that is still relatively natural.

The Cuyama Valley is a valley along the Cuyama River in central California, in northern Santa Barbara, southern San Luis Obispo, southwestern Kern, and northwestern Ventura counties. It is about two hours driving time from both Los Angeles and the Santa Barbara area.

The San Buenaventura Mission Aqueduct was a seven-mile long, stone and mortar aqueduct built in the late 18th and/or early 19th century to transport water from the Ventura River to the Mission San Buenaventura in Ventura, California.

Rancho Ex-Mission San Buenaventura was a 48,823-acre (197.58 km2) Mexican land grant in present-day Ventura County, California given in 1846 by Governor Pio Pico to José de Arnaz. The grant derives its name from the secularized Mission San Buenaventura, and was called ex-Mission because of a division made of the lands held in the name of the Mission — the church retaining the grounds immediately around, and all of the lands outside of this are called ex-Mission lands. The grant extended east from present day Ventura, excluding the Rancho San Miguel (Olivas) lands, inland up the Santa Clara River to Santa Paula, between the north bank of the River and Sulphur Mountain.

Rancho Boca de la Playa was a 6,607-acre (26.74 km2) Mexican land grant in present-day Orange County, California given in 1846 by Governor Pío Pico to Emigdio Vejar. The name refers to the wetlands estuary at the 'mouth of the beach,' or 'boca de la playa' in Spanish. This is the most southerly grant in Orange County, and extended along the Pacific coast from San Juan Creek in the south of present-day San Juan Capistrano south to San Clemente.

Lockwood Valley is an unincorporated community located in an eponymous valley in northeastern Ventura County, southern California, and part of the Mountain Communities of the Tejon Pass.

Cuddy Canyon is a canyon running along the boundary line between Kern County and Ventura County, California. It lies inside the Los Padres National Forest and southern San Emigdio Mountains.

Ortega Adobe is a historic adobe house built in 1857 and located on Main Street on the west side of Ventura, California, not far from the mouth of the Ventura River. It was designated in 1974 as the City of Ventura's Historic Landmark No. 2. It is owned by the City and operated as a self-guided historical site.

The Santa Gertrudis Asistencia, also known as the Santa Gertrudis Chapel, was an asistencia ("sub-mission") to the Mission San Buenaventura, part of the system of Spanish missions in Las Californias—Alta California. Built at an unknown date between 1792 and 1809, it was located approximately five miles from the main mission, inland and upstream along the Ventura River. The site was buried in 1968 by the construction of California State Route 33. Prior to the freeway's construction, archaeologists excavated and studied the site. A number of foundation stones were moved and used to create the Santa Gertrudis Asistencia Monument which was designated in 1970 as Ventura County Historic Landmark No. 11.

Annie Lydia Rose was a gold prospector and mining entrepreneur active between 1910 and 1972 in Bear Canyon and adjoining Pine Canyon in the north-west corner of the Angeles National Forest. She was uncharacteristically bold beyond her age, gender, and the restraints of the late Victorian era in which she grew up. During her life and now through her legacy, she is considered an authority on the legendary Lost Horse Mine also referred to as the Lost Padre Mine.

Chief Tecuya was an Emigdiano Chumash elder said to be the last living soul to have known the precise whereabouts of an exposed gold ledge that spawned the legend of the Lost Padre Mine.

The Battle of San Buenaventura was a battle fought on March 27 and March 28, 1838, between forces representing competing claims to the governorship of California, then a Mexican territory. The opposing forces consisted of supporters of Juan Bautista Alvarado based in Northern California and supporters of Carlos Antonio Carrillo from Southern California. The major action consisted of a cannon siege on the Carrillo loyalists who were encamped at the Mission San Buenaventura in Ventura, California. The Alvarado forces won the battle, as the Carrillo forces fled from the Mission under cover of darkness following the first day of the battle. Most of the Carillo forces were captured the following day at Saticoy, California. One person was killed in the battle, an Alvarado loyalist who was shot by a rifleman stationed in the Mission's bell tower.