Related Research Articles

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science and various areas of analytic philosophy, especially philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics.

Epistemology, or the theory of knowledge, is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemology is considered a major subfield of philosophy, along with other major subfields such as ethics, logic, and metaphysics.

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empiricism emphasizes the central role of empirical evidence in the formation of ideas, rather than innate ideas or traditions. However, empiricists may argue that traditions arise due to relations of previous sensory experiences.

Thomas Reid was a religiously trained Scottish philosopher. He was the founder of the Scottish School of Common Sense and played an integral role in the Scottish Enlightenment. In 1783 he was a joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. A contemporary of David Hume, Reid was also "Hume's earliest and fiercest critic".

Suspension of disbelief, sometimes called willing suspension of disbelief, is the avoidance of critical thinking or logic in examining something unreal or impossible in reality, such as a work of speculative fiction, in order to believe it for the sake of enjoyment. Aristotle first explored the idea of the concept in its relation to the principles of theater; the audience ignores the unreality of fiction in order to experience catharsis.

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, natively Radhakrishnayya, was an Indian philosopher and statesman. He served as the second president of India from 1962 to 1967. He was also the first vice president of India from 1952 to 1962. He was the second ambassador of India to the Soviet Union from 1949 to 1952. He was also the fourth vice-chancellor of Banaras Hindu University from 1939 to 1948 and the second vice-chancellor of Andhra University from 1931 to 1936.

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification". More formally, rationalism is defined as a methodology or a theory "in which the criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive".

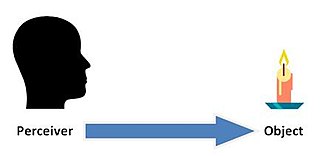

In the philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, the question of direct or naïve realism, as opposed to indirect or representational realism, is the debate over the nature of conscious experience; out of the metaphysical question of whether the world we see around us is the real world itself or merely an internal perceptual copy of that world generated by our conscious experience.

Cyril Edwin Mitchinson Joad was an English philosopher, author, teacher and broadcasting personality. He appeared on The Brains Trust, a BBC Radio wartime discussion programme. He popularised philosophy and became a celebrity, before his downfall in a scandal over an unpaid train fare in 1948.

Philosophical realism is usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters. Realism about a certain kind of thing is the thesis that this kind of thing has mind-independent existence, i.e. that it is not just a mere appearance in the eye of the beholder. This includes a number of positions within epistemology and metaphysics which express that a given thing instead exists independently of knowledge, thought, or understanding. This can apply to items such as the physical world, the past and future, other minds, and the self, though may also apply less directly to things such as universals, mathematical truths, moral truths, and thought itself. However, realism may also include various positions which instead reject metaphysical treatments of reality entirely.

An Essay Concerning Human Understanding is a work by John Locke concerning the foundation of human knowledge and understanding. It first appeared in 1689 with the printed title An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding. He describes the mind at birth as a blank slate filled later through experience. The essay was one of the principal sources of empiricism in modern philosophy, and influenced many enlightenment philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley.

John Henry Muirhead was a British philosopher best known for having initiated the Muirhead Library of Philosophy in 1890. He became the first person named to the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Birmingham in 1900.

The argument from illusion is an argument for the existence of sense-data. It is posed as a criticism of direct realism.

The aspects of Bertrand Russell's views on philosophy cover the changing viewpoints of philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell (1872–1970), from his early writings in 1896 until his death in February 1970.

Aspects of philosopher, mathematician and social activist Bertrand Russell's views on society changed over nearly 80 years of prolific writing, beginning with his early work in 1896, until his death in February 1970.

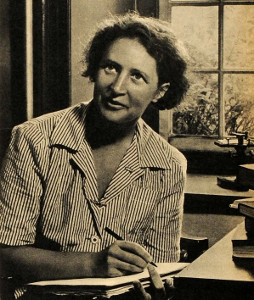

Susanne Katherina Langer was an American philosopher, writer, and educator known for her theories on the influences of art on the mind. She was one of the earliest American women to achieve an academic career in philosophy and the first woman to be professionally recognized as an American philosopher. Langer is best remembered for her 1942 book Philosophy in a New Key which was followed by a sequel Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art in 1953. In 1960, Langer was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The theory of sense data is a view in the philosophy of perception, popularly held in the early 20th century by philosophers such as Bertrand Russell, C. D. Broad, H. H. Price, A. J. Ayer, and G. E. Moore. Sense data are taken to be mind-dependent objects whose existence and properties are known directly to us in perception. These objects are unanalyzed experiences inside the mind, which appear to subsequent more advanced mental operations exactly as they are.

Relations are ways in which things, the relata, stand to each other. Relations are in many ways similar to properties in that both characterize the things they apply to. Properties are sometimes treated as a special case of relations involving only one relatum. In philosophy, theories of relations are typically introduced to account for repetitions of how several things stand to each other.

Romantic epistemology emerged from the Romantic challenge to both the static, materialist views of the Enlightenment (Hobbes) and the contrary idealist stream (Hume) when it came to studying life. Romanticism needed to develop a new theory of knowledge that went beyond the method of inertial science, derived from the study of inert nature, to encompass vital nature. Samuel Taylor Coleridge was at the core of the development of the new approach, both in terms of art and the 'science of knowledge' itself (epistemology). Coleridge's ideas regarding the philosophy of science involved Romantic science in general, but Romantic medicine in particular, as it was essentially a philosophy of the science(s) of life.

Charles Arthur Campbell was a Scottish metaphysical philosopher.

References

- ↑ Brown, Stuart, ed. (2005). Dictionary of Twentieth-Century British Philosophers: 2 Volumes. Bristol, England: Thoemmes Continuum. p. 867. ISBN 9781843710967.

- ↑ Richard Aldrich, The Institute of Education 1902–2002: A Centenary History.

- ↑ Trilling wrote the introduction to the first American edition of A Study in Aesthetics (Reader's Subscription Inc, 1954).

- ↑ There is a Wikipedia entry for Harold Osborne in Spanish.

- ↑ Barzun, Jacques. Berlioz and the Romantic Century. Columbia UP (1969.) I.179n.

- ↑ Ayer, A.J.. Part of My Life, Collins (1984.) 308.

- ↑ Biographical details come from Reid's memoir, Yesterdays Today. Canberra: Samizdat Press (CreateSpace), 2013.

- ↑ L.A. Reid, Knowledge and Truth, Macmillan (1923) 105, 113.

- ↑ Mary Warnock, Imagination. London: Faber, 1976.

- ↑ For an exposition of Reid’s views, see Nicholas Reid, Coleridge, Form and Symbol. Ashgate (2006) chapter 1.

- ↑ See Meaning in the Arts. George Allen and Unwin (1969).

- ↑ L.A. Reid, '’Knowledge and Truth'’, Macmillan (1923) chapter 9; and in many other places; 'Art and Knowledge'. British Journal of Aesthetics (1985) 25 (2):115–125.

- ↑ Louis Arnaud, Reid (1961). Ways of Knowledge and Experience. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Sussanne Langer, Feeling and Form. Routledge and Kegan Paul (1953).

- ↑ Antonio Damasio, Descartes' Error. Putnam (1994).

- ↑ Nicholas Humphrey, A History of the Mind. Simon and Schuster (1992).

- ↑ George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. Basic Books (1999).

- ↑ J.H. Muirhead, Coleridge as Philosopher. George Allen and Unwin (1930).

- ↑ L.A. Reid, '’Philosophy and Education: An Introduction’’, Heinemann (1962).