Sudovian was a West Baltic language of Northeastern Europe. Sudovian was closely related to Old Prussian. It was formerly spoken southwest of the Neman river in what is now Lithuania, east of Galindia and in the north of Yotvingia, and by exiles in East Prussia.

Old Prussians, Baltic Prussians or simply Prussians were a Baltic people that inhabited the region of Prussia, on the southeastern shore of the Baltic Sea between the Vistula Lagoon to the west and the Curonian Lagoon to the east. As Balts, they spoke an Indo-European language of the Baltic branch now known as Old Prussian and worshipped pre-Christian deities. Their ethnonym was later adopted by predominantly Low German-speaking inhabitants of the region.

Aukštaitija is the name of one of five ethnographic regions of Lithuania. The name comes from the fact that the lands are in the upper basin of the Nemunas, as opposed to the Lowlands that begin from Šiauliai westward. Although Kaunas is surrounded by Aukštaitija, the city itself is not considered to be a part of any ethnographic region in most cases.

The Scalovians, also known as the Skalvians, Schalwen and Schalmen, were a Baltic tribe related to the Prussians. According to the Chronicon terrae Prussiae of Peter of Dusburg, the now extinct Scalovians inhabited the land of Scalovia south of the Curonians and Samogitians, by the lower Neman River ca. 1240.

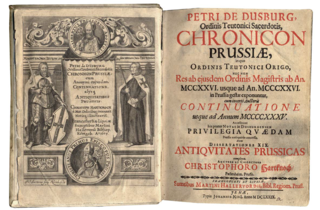

Chronicon terræ Prussiæ is a chronicle of the Teutonic Knights, by Peter of Dusburg, finished in 1326. The manuscript is the first major chronicle of the Teutonic Order in Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, completed some 100 years after the conquest of the crusaders into the Baltic region. It is a major source for information on the Order's battles with Old Prussians and Lithuanians.

Peter of Dusburg, also known as Peter of Duisburg, was a Priest-Brother and chronicler of the Teutonic Knights. He is known for writing the Chronicon terrae Prussiae, which described the 13th and early 14th century Teutonic Knights and Old Prussians in Prussia.

Luther von Braunschweig was a German nobleman who served as the 18th Grand Master of the Teutonic Order from 1331 to 1335.

Scalovia or Skalvia was the area of Prussia originally inhabited by the now extinct Baltic tribe of Skalvians or Scalovians which according to the Chronicon terrae Prussiae of Peter of Dusburg lived to the south of the Curonians, by the lower Nemunas river, in the times around 1240.

Komantas or Skomantas was a powerful duke and pagan priest of the Yotvingians, one of the early Baltic tribes. He was at the height of his power during the 1260s and 1270s.

The Prussian Crusade was a series of 13th-century campaigns of Roman Catholic crusaders, primarily led by the Teutonic Knights, to Christianize under duress the pagan Old Prussians. Invited after earlier unsuccessful expeditions against the Prussians by Christian Polish princes, the Teutonic Knights began campaigning against the Prussians, Lithuanians and Samogitians in 1230. By the end of the century, having quelled several Prussian uprisings, the Knights had established control over Prussia and administered the conquered Prussians through their monastic state, eventually erasing the Prussian language, culture and pre-Christian religion by a combination of physical and ideological force. Some Prussians took refuge in neighboring Lithuania.

Nikolaus von Jeroschin was a 14th-century German chronicler of the Teutonic Knights in Prussia.

Prussian Chronicle or Teutonic Chronicle can refer to one of the several medieval chronicles:

The siege of Medvėgalis was a brief siege of Medvėgalis, a Lithuanian fortress in Samogitia, in February 1329 by the Teutonic Order reinforced by many guest crusaders, including King John of Bohemia. The 18,000-strong Teutonic army captured four Lithuanian fortresses and besieged Medvėgalis. The fortress surrendered, and as many as 6,000 locals were baptized in the Catholic rite. The campaign, which lasted a little more than a week, was cut short by a Polish attack on Prussia in the Polish–Teutonic War (1326–32). When the Teutonic army returned to Prussia, the Lithuanians returned to their pagan practices and beliefs.

Landmeister in Livland was a high office in the Teutonic Order. The Landmeister administered the Livonia of the Teutonic Order. These lands had fallen to the Teutonic Order in 1237 by the incorporation of the former Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The seat of the Landmeister was castle Wenden. The Landmaster's function in Livonia lasted until 1561, when in aftermath of Livonian War the last Landmeister Gotthard Kettler relinquished the northern parts of the Mastery and in the Union of Vilna secularized the part still left to him and, as the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, took fief from the Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania Sigismund II Augustus. The non-recognition of this act by Pope, Holy Roman Empire and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order had no factual effect.

Kriwe Kriwaito or simply Kriwe was the chief priest in the old Baltic religion. Known primarily from the dubious 16th-century writings of Simon Grunau, the concept of kriwe became popular during the times of romantic nationalism. However, lack of reliable written evidence has led some researchers to question whether such pagan priest actually existed. The title was adopted by Romuva, the neo-pagan movement in Lithuania, when Jonas Trinkūnas was officially installed as krivių krivaitis in October 2002.

Stenckel von Bentheim, also known as Sсhenckel von Bentheim and Seno von Bynthausen, was a knight of Westphalia mentioned in The Chronicle of the Prussian Land by Peter of Dusburg and the eponymous The Chronicle of Prussia by Nikolaus von Jeroschin. He took part as a so-called guest knight in the Prussian Crusade and died in the Battle of Pokarwis in 1261, as described by Peter of Dusburg and Nikolaus von Jeroschin in the aforementioned chronicles:

The brothers and the Christians fought back valiantly, particularly one, a good pure knight called Lord Schenckel of Bentheim who came from Westphalia. He had heard a bishop there preaching to the people that all of the Christian souls who were killed by the heathens in Prussia entered heaven directly without going through purgatory. This reward was precious above all others to this knight. He spurred on his horse and charged, carrying his spear as knights do, and charged through the enemy front line and into the main army. His charge inflicted serious injury on many Prussians; his sharpedged salute killed many on both sides. When he had charged through them, and he was turning back and had reached the middle of the army, this laudable warrior of God was knocked down.

The Battle of Wopławki or Woplauken was fought on 7 April 1311 in the area near the village of Woplauken, north-east of Kętrzyn. Belarusian historian Ruslan Gagua states in Annalistic Records on the Battle of WopławkiArchived 2020-06-26 at the Wayback Machine The battle definitely had become a major and significant one by medieval standards during the military confrontation of the Teutonic Order and the then Lithuania, according to The Nature of the Conduct of Warfare in Prussian and Lithuanian Borderlands at the Turn of the 13th and 14th Centuries by Ruslan Gagua.

Bertold Brühaven, also known as Berthold von Brühaven or Berthold von Bruehaven, was a Teutonic knight hailed from the then Duchy of Austria; served in Prussia as the Komtur of Balga in 1288–1289, the first Komtur of Ragnit in 1289, then the Komtur of Königsberg in from 1289 to 1302.

Heinrich Stange was a Teutonic knight who served in the land of Prussia administered by the Teutonic Order as the Komtur of Christburg from 1249 to 1252, simultaneously holding the position of the Vice Landmeister of Prussia.

Ernst Strehlke was a German historian and archivist. He dedicated his rather short life to the history of the Teutonic Order.