Related Research Articles

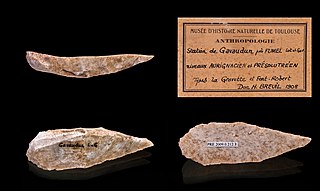

A microlith is a small stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 35,000 to 3,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia. The microliths were used in spear points and arrowheads.

The Natufian culture is a Late Epipaleolithic archaeological culture of the Neolithic prehistoric Levant in Western Asia, dating to around 15,000 to 11,500 years ago. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentary or semi-sedentary population even before the introduction of agriculture. The Natufian communities may be the ancestors of the builders of the first Neolithic settlements of the region, which may have been the earliest in the world. Some evidence suggests deliberate cultivation of cereals, specifically rye, by the Natufian culture at Tell Abu Hureyra, the site of earliest evidence of agriculture in the world. The world's oldest known evidence of the production of bread-like foodstuff has been found at Shubayqa 1, a 14,400-year-old site in Jordan's northeastern desert, 4,000 years before the emergence of agriculture in Southwest Asia In addition, the oldest known evidence of possible beer-brewing, dating to approximately 13,000 BP, was found in Raqefet Cave on Mount Carmel, although the beer-related residues may simply be a result of a spontaneous fermentation.

In archaeology, in particular of the Stone Age, lithic reduction is the process of fashioning stones or rocks from their natural state into tools or weapons by removing some parts. It has been intensely studied and many archaeological industries are identified almost entirely by the lithic analysis of the precise style of their tools and the chaîne opératoire of the reduction techniques they used.

In archaeology, a lithic flake is a "portion of rock removed from an objective piece by percussion or pressure," and may also be referred to as simply a flake, or collectively as debitage. The objective piece, or the rock being reduced by the removal of flakes, is known as a core. Once the proper tool stone has been selected, a percussor or pressure flaker is used to direct a sharp blow, or apply sufficient force, respectively, to the surface of the stone, often on the edge of the piece. The energy of this blow propagates through the material, often producing a Hertzian cone of force which causes the rock to fracture in a controllable fashion. Since cores are often struck on an edge with a suitable angle (<90°) for flake propagation, the result is that only a portion of the Hertzian cone is created. The process continues as the flintknapper detaches the desired number of flakes from the core, which is marked with the negative scars of these removals. The surface area of the core which received the blows necessary for detaching the flakes is referred to as the striking platform.

In archaeology, a lithic core is a distinctive artifact that results from the practice of lithic reduction. In this sense, a core is the scarred nucleus resulting from the detachment of one or more flakes from a lump of source material or tool stone, usually by using a hard hammer precursor such as a hammerstone. The core is marked with the positive scars of these flakes. The surface area of the core which received the blows necessary for detaching the flakes is referred to as the striking platform. The core may be discarded or shaped further into a core tool, such as can be seen in some types of handaxe.

Harifian is a specialized regional cultural development of the Epipalaeolithic of the Negev Desert. It corresponds to the latest stages of the Natufian culture.

In prehistoric archaeology, scrapers are unifacial tools thought to have been used for hideworking and woodworking. Many lithic analysts maintain that the only true scrapers are defined on the base of use-wear, and usually are those that were worked on the distal ends of blades—i.e., "end scrapers". Other scrapers include the so-called "side scrapers" or racloirs, which are made on the longest side of a flake, and notched scrapers, which have a cleft on either side that may have been used to attach them to something else.

Ohalo II is an archaeological site in Northern Israel, near Kinneret, on the southwest shore of the Sea of Galilee. It is one of the best preserved hunter-gatherer archaeological sites of the Last Glacial Maximum, radiocarbon dated to around 23,000 BP (calibrated). It is at the junction of the Upper Paleolithic and the Epipaleolithic, and has been attributed to both periods. The site is significant for two findings which are the world's oldest: the earliest brushwood dwellings and evidence for the earliest small-scale plant cultivation, some 11,000 years before the onset of agriculture. The numerous fruit and cereal grain remains preserved in anaerobic conditions under silt and water are also exceedingly rare due to their general quick decomposition.

The prehistory of the Levant includes the various cultural changes that occurred, as revealed by archaeological evidence, prior to recorded traditions in the area of the Levant. Archaeological evidence suggests that Homo sapiens and other hominid species originated in Africa and that one of the routes taken to colonize Eurasia was through the Sinai Peninsula desert and the Levant, which means that this is one of the most important and most occupied locations in the history of the Earth. Not only have many cultures and traditions of humans lived here, but also many species of the genus Homo. In addition, this region is one of the centers for the development of agriculture.

Sickle-gloss, or sickle sheen, is a silica residue found on blades such as sickles and scythes suggesting that they have been used to cut the silica-rich stems of cereals and forming an indirect proof for incipient agriculture. The gloss occurs from the abrasive action of silica in both wild and cultivated stems of cereal grasses, meaning the occurrence of reaping tools with sickle gloss doesn't necessarily imply agriculture. The first documented appearance of sickle-gloss is found on flint knapped blades in the Natufian culture in the Middle East, primarily in Israel.

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is locally known as the Eastern Oranian. The Iberomaurusian seems to have appeared around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), somewhere between c. 25,000 and 23,000 cal BP. It would have lasted until the early Holocene c. 11,000 cal BP.

Adrian Nigel Goring-Morris is a British-born archaeologist and a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel. He completed his PhD there in 1986 and is notable for his work and discoveries at one of the oldest ritual burial sites in the world; Kfar HaHoresh. The earliest levels of this site have been dated to 8000 BC and it is located in the northern Israel, not far from Nazareth.

Shuqba cave is an archaeological site near the town of Shuqba in the western Judaean Mountains in the Ramallah and al-Bireh Governorate of the West Bank.

Shell tools, in the archaeological perspective, were tools fashioned by pre-historic humans from shells in lieu of stone tools. The use of shell tools during pre-historic times was a practice common to inhabitants of environments that lack the abundance of hard stones for making tools. This was the case with the islands surrounding the Pacific, including the Philippines. Shells were fashioned into tools, as well as ornaments. From adzes, scoops, spoons, dippers and other tools to personal ornaments such as earrings, anklets, bracelets and beads. These different artefacts made of shells were unearthed from various archaeological sites from the country.

The Kalemba Rockshelter is an archaeology site located in eastern Zambia, at coordinates 14°7 S and 32°3 E. Local tradition recalls the use of the rock shelter as a refuge during the time of Ngoni raiding in the 19th century. The site is known for various rock paintings as well as advanced microlithic use.

Trialetian is the name for an Upper Paleolithic-Epipaleolithic stone tool industry from the South Caucasus. It is tentatively dated to the period between 16,000 / 13,000 BP and 8,000 BP.

Chipped stone crescents are a class of artifact found mainly associated with surface components of archaeological sites located in the Great Basin, the Columbia Plateau, and throughout California. Although their distribution covers a large portion of the western United States, crescents are often found in similar contexts in close proximity to water sources including playas, lakes, rivers, and mainland and island coast lines. Crescents are generally thought to be diagnostic to the terminal Pleistocene and early Holocene and are representative of assemblages that include fluted and stemmed projectile points.

R12 is a middle Neolithic cemetery located in the Northern Dongola Reach on the banks of the Seleim Nile palaeochannel of modern-day Sudan. The site is dated to between 5000 and 4000 BC. Centro Veneto di Studi Classici e Orientali excavated the site, within the concession of the Sudan Archaeological Research Society and after an agreement with it, between 2000 and 2003 over three digging seasons. The first was in 2000 and 33 graves were discovered. The second was in 2001 and another 33 graves were discovered. The third was in 2003 and the last 100 graves were discovered. There are 166 graves total at the site. Contents of the graves include ceramics, animal bones, grinding stones, human skeletons, and plant remains.

The Lodian culture or Jericho IX culture is a Pottery Neolithic archaeological culture of the Southern Levant dating from the first half of the 5th millennium BC, existing alongside the Yarmukian and Nizzanim cultures. The Lodian culture appears mainly in areas south of the territory of the Yarmukian culture, in the Shfela and the beginning of the Israeli coastal plain; the Judaean Mountains, and in the desert regions around the Dead Sea and south of it.

Bone Cave, located in the Middle Weld Valley of Tasmania, is a small vertical limestone cave with a rich history of human occupation.

References

- ↑ "lunate - definition of lunate by the Free Online Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia". Thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ↑ Rosen, Steve A. (1983). "The Microlithic Lunate : An Old-New Tool Type from the Negev, Israel". Paléorient. 9 (2): 81–83. doi:10.3406/paleo.1983.4345.

- ↑ Adkin, G. Leslie (1957). "A rare lunate pendant from New Zealand". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 66 (2): 192–198.

- ↑ Wheeler, Richard Page (1965). "Edge-Abraded Flakes, Blades, and Cores in the Puebloan Tool Assemblage". Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology. 19 (19): 19–29. doi:10.1017/S0081130000004354. JSTOR 25146663.