The American Association of University Women (AAUW), officially founded in 1881, is a non-profit organization that advances equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research. The organization has a nationwide network of 170,000 members and supporters, 1,000 local branches, and 800 college and university partners. Its headquarters are in Washington, D.C. AAUW's CEO is Gloria L. Blackwell.

The Comisión Femenil Mexicana Nacional was a Mexican-American organization dedicated to economically and politically empowering Chicana women in the United States.

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement in the United States that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation. Chicanos also expressed solidarity and defined their culture through the development of Chicano art during El Movimiento, and stood firm in preserving their religion.

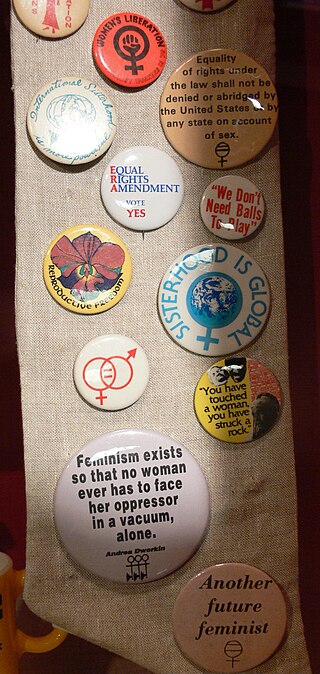

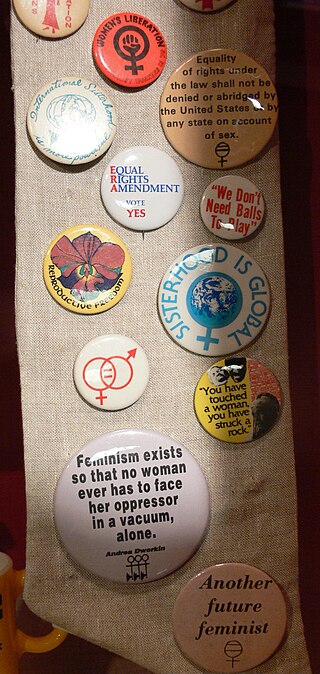

Chicana feminism is a sociopolitical movement, theory, and praxis that scrutinizes the historical, cultural, spiritual, educational, and economic intersections impacting Chicanas and the Chicana/o community in the United States. Chicana feminism empowers women to challenge institutionalized social norms and regards anyone a feminist who fights for the end of women's oppression in the community.

Polly Baca is an American politician who served as Chair of the Democratic Caucus of the Colorado House of Representatives (1976–79), being the first woman to hold that office and the first Hispanic woman elected to the Colorado State Senate and in the House and Senate of a state Legislature.

A variety of movements of feminist ideology have developed over the years. They vary in goals, strategies, and affiliations. They often overlap, and some feminists identify themselves with several branches of feminist thought.

Helen Fabela Chávez was an American labor activist for the United Farm Workers of America (UFWA). Aside from her affiliation with the UFW, she was a Chicana with a traditional upbringing and limited education. She was also the wife of Cesar Chavez.

Latin American feminism is a collection of movements aimed at defining, establishing, and achieving equal political, economic, cultural, personal, and social rights for Latin American women. This includes seeking to establish equal opportunities for women in education and employment. People who practice feminism by advocating or supporting the rights and equality of women are feminists.

The 1977 National Women's Conference was held November 18–21, in Houston, Texas, United States. The purpose of this conference was to celebrate International Women's Year and also to create resolutions for women to discuss and address.

Hijas de Cuauhtémoc was a student Chicana feminist newspaper founded in 1971 by Anna Nieto-Gómez and Adelaida Castillo while both were students at California State University, Long Beach.

Multiracial feminist theory refers to scholarship written by women of color (WOC) that became prominent during the second-wave feminist movement. This body of scholarship "does not offer a singular or unified feminism but a body of knowledge situating women and men in multiple systems of domination."

Patricia Zavella is an anthropologist and professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz in the Latin American and Latino Studies department. She has spent a career advancing Latina and Chicana feminism through her scholarship, teaching, and activism. She was president of the Association of Latina and Latino Anthropologists and has served on the executive board of the American Anthropological Association. In 2016, Zavella received the American Anthropological Association's award from the Committee on Gender Equity in Anthropology to recognize her career studying gender discrimination. The awards committee said Zavella's career accomplishments advancing the status of women, and especially Latina and Chicana women have been exceptional. She has made critical contributions to understanding how gender, race, nation, and class intersect in specific contexts through her scholarship, teaching, advocacy, and mentorship. Zavella's research focuses on migration, gender and health in Latina/o communities, Latino families in transition, feminist studies, and ethnographic research methods. She has worked on many collaborative projects, including an ongoing partnership with Xóchitl Castañeda where she wrote four articles some were in English and others in Spanish. The Society for the Anthropology of North America awarded Zavella the Distinguished Career Achievement in the Critical Study of North America Award in the year 2010. She has published many books including, most recently, I'm Neither Here Nor There, Mexicans' Quotidian Struggles with Migration and Poverty, which focuses on working class Mexican Americans struggle for agency and identity in Santa Cruz County.

The Chicana Rights Project(CRP) was a feminist organization created in 1974 to address the legal rights of poor Mexican-American women. The organization was guided by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and created by Vilma Martinez. The project was headquartered in San Francisco and San Antonio.

La Conferencia de Mujeres por la Raza was held in Houston, Texas, between May 28 and May 30 in 1971. The conference marked the first time Chicanas came together within the state from around the country to discuss issues important to feminism and Chicana women. It was considered the first conference of its kind by the Corpus Christi Caller-Times.

Las Hermanas is a feminist, autonomous Roman Catholic organization created between 1970 and 1971 for Hispanic women who are involved in the Catholic Church. It was incorporated in Texas in 1972 and was the first group in the Church in the United States to represent Spanish-speaking women. Las Hermanas has worked for the improvement of the lives of religious Hispanic women and their communities. They are outspoken critics of sexism in the Church and their communities. Las Hermanas is very political and has taken part in protests and other civil rights actions. The organization is currently considered to be on "hiatus," with plans to continue their work in the future.

Sister Alicia Valladolid Cuarón is an American educator, human rights activist, women's rights activist, leadership development specialist, and Franciscan nun. Since the 1970s, she has crafted numerous initiatives benefiting low-income Latinas and Spanish-speaking immigrant families in Colorado, including the first bilingual and bicultural Head Start program in the state, the national Adelante Mujer Hispanic Employment and Training Conference, and the Bienestar Family Services Center, today a ministry of the Archdiocese of Denver. In 1992, Cuarón joined the Sisters of St. Francis of Penance and Christian Charity, where she continues her efforts to promote education and leadership development among Spanish-speaking families. She was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 2008.

Mujeres Activas en Letras Y Cambio Social (MALCS) is an inclusive organization of Chicana, Latina, Native American and gender non-conforming academics, students, and activists. MALCS focuses on recognizing the hard work of contributors to the organization, giving women access to higher education, and educating society about the issues they face. MALCS was established in 1982 at the University of California, Davis after noticing no change was being made during the Chicano Movement despite their activism efforts. To continue their efforts in unifying women, they provide membership opportunities and benefits such as access to their summer institute and their peer-reviewed journal: Chicana/Latina Studies which talks about the experiences of Latina women. This organization helps bring them together to share their thoughts, opinions, and information about things they want to work on, current issues, or anything. They also bring together their research and community involvement to create social change. It is a safe space for everyone to uplift and support one another.

Deena J. González is a Mexican-American historian and former Provost and Senior Vice President of Gonzaga University (GU). González is responsible for the releasing over 50 academic publications over the history of Chicanos/as and their presence in the United States. She is also a founding member of the national organization, Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social (MALCS), that promotes research in Chicana, Latina, Native American, and Indigenous communities.

The queer Chicano art scene emerged from Los Angeles during the late 1960s and early 1990s composing of queer Mexican American artists. The scene’s activity included motives and themes relating to political activism, social justice, and identity. The movement was influenced by the respective movements of gay liberation, Chicano civil rights, and women’s liberation. The social and political conditions impacting Chicano communities as well as queer people, including the HIV/AIDS epidemic, are conveyed in the scene’s expressive work.