Sailing employs the wind—acting on sails, wingsails or kites—to propel a craft on the surface of the water, on ice (iceboat) or on land over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation.

Seamanship is the art, competence, and knowledge of operating a ship, boat or other craft on water. The Oxford Dictionary states that seamanship is "The skill, techniques, or practice of handling a ship or boat at sea."

A dinghy is a type of small boat, often carried or towed by a larger vessel for use as a tender. Utility dinghies are usually rowboats or have an outboard motor. Some are rigged for sailing but they differ from sailing dinghies, which are designed first and foremost for sailing. A dinghy's main use is for transfers from larger boats, especially when the larger boat cannot dock at a suitably-sized port or marina.

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium. On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw and p-factor and is not the primary control used to turn the airplane. A rudder operates by redirecting the fluid past the hull or fuselage, thus imparting a turning or yawing motion to the craft. In basic form, a rudder is a flat plane or sheet of material attached with hinges to the craft's stern, tail, or afterend. Often rudders are shaped to minimize hydrodynamic or aerodynamic drag. On simple watercraft, a tiller—essentially, a stick or pole acting as a lever arm—may be attached to the top of the rudder to allow it to be turned by a helmsman. In larger vessels, cables, pushrods, or hydraulics may link rudders to steering wheels. In typical aircraft, the rudder is operated by pedals via mechanical linkages or hydraulics.

The weather gage is the advantageous position of a fighting sailing vessel relative to another. It is also known as "nautical gauge" as it is related to the sea shore. The concept is from the Age of Sail and is now antique. A ship at sea is said to possess the weather gage if it is in any position upwind of the other vessel. Proximity with the land, tidal and stream effects and wind variability due to geography may also come into play.

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

A jibe (US) or gybe (Britain) is a sailing maneuver whereby a sailing craft reaching downwind turns its stern through the wind, which then exerts its force from the opposite side of the vessel. It stands in contrast with tacking, whereby the sailing craft turns its bow through the wind.

The radiotelephony message PAN-PAN is the international standard urgency signal that someone aboard a boat, ship, aircraft, or other vehicle uses to declare that they need help and that the situation is urgent, but for the time being, does not pose an immediate danger to anyone's life or to the vessel itself. This is referred to as a state of "urgency". This is distinct from a mayday call, which means that there is imminent danger to life or to the continued viability of the vessel itself. Radioing "pan-pan" informs potential rescuers that an urgent problem exists, whereas "mayday" calls on them to drop all other activities and immediately begin a rescue.

A tiller or till is a lever used to steer a vehicle. The mechanism is primarily used in watercraft, where it is attached to an outboard motor, rudder post or stock to provide leverage in the form of torque for the helmsman to turn the rudder. A tiller may also be used in vehicles outside of water, and was seen in early automobiles.

1 Main Circuit (1MC) is the term for the shipboard public address circuits on United States Navy and United States Coast Guard vessels. This provides a means of transmitting general information and orders to all internal ship spaces and topside areas, and is loud enough that all embarked personnel are (normally) able to hear it. It is used to put out general information to the ship's crew on a regular basis each day. The system consists of an amplifier-oscillator group which is located in the IC/gyro room, a microphone control station, portable microphones at each control station and loudspeakers located throughout the ship. Control stations for the 1MC announcing system are located at the pilot house, OOD stations on the quarterdecks, aft steering and Damage Control Central area.

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water. Some remain current, while many date from the 17th to 19th centuries. The word nautical derives from the Latin nauticus, from Greek nautikos, from nautēs: "sailor", from naus: "ship".

Stays are ropes, wires, or rods on sailing vessels that run fore-and-aft along the centerline from the masts to the hull, deck, bowsprit, or to other masts which serve to stabilize the masts.

A helmsman or helm is a person who steers a ship, sailboat, submarine, other type of maritime vessel, airship, or spacecraft. The rank and seniority of the helmsman may vary: on small vessels such as fishing vessels and yachts, the functions of the helmsman are combined with that of the skipper; on larger vessels, there is a separate officer of the watch who is responsible for the safe navigation of the ship and gives orders to the helmsman, who physically steers the ship in accordance with those orders.

"Man overboard!" is an exclamation given aboard a vessel to indicate that a member of the crew or a passenger has fallen off of the ship into the water and is in need of immediate rescue. Whoever sees the person fall is to shout, "Man overboard!" and the call is then to be reported once by every crewman within earshot, even if they have not seen the victim fall, until everyone on deck has heard and given the same call. This ensures that all other crewmen have been alerted to the situation and notifies the officers of the need to act immediately to save the victim. Pointing continuously at the victim may aid the helmsman in approaching the victim.

Model yachting is the pastime of building and racing model yachts. It has always been customary for ship-builders to make a miniature model of the vessel under construction, which is in every respect a copy of the original on a small scale, whether steamship or sailing ship. There are fine collections to be seen at both general interest museums such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and at many specialized maritime museums worldwide. Many of these models are of exquisite workmanship, every rope, pulley or portion of the engine being faithfully reproduced. In the case of sailing yachts, these models were often pitted against each other on small bodies of water, and hence arose the modern pastime. It was soon seen that elaborate fittings and complicated rigging were a detriment to rapid handling, and that, on account of the comparatively stronger winds in which models were sailed, they needed a greater draught. For these reasons modern model yachts, which usually have fin keels, are of about 15% or 20% deeper draught than full-sized vessels, while rigging and fittings have been reduced to absolute simplicity. This applies to models built for racing and not to elaborate copies of steamers and ships, made only for show or for " toy cruising."

In sailing, heaving to is a way of slowing a sailing vessel's forward progress, as well as fixing the helm and sail positions so that the vessel does not have to be steered. It is commonly used for a "break"; this may be to wait for the tide before proceeding, or to wait out a strong or contrary wind. For a solo or shorthanded sailor it can provide time to go below deck, to attend to issues elsewhere on the boat or to take a meal break. Heaving to can make reefing a lot easier, especially in traditional vessels with several sails. It is also used as a storm tactic.

There are two different meanings to the term lee helm depending on whether one is discussing sailboats or motorized ships.

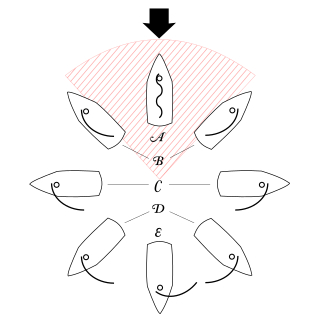

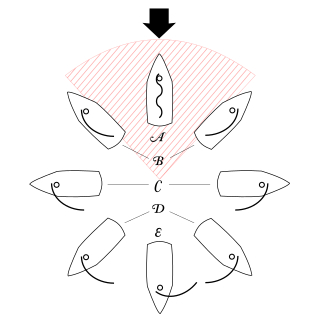

A teardrop turn is a method of reversing the course of an aircraft or vessel so that it returns on its original path, travelling in the opposite direction, and passes through a specified point on the original path.

HMPNGS Seeadler (P03) is one of four Pacific Forum patrol vessels operated by the Papua New-Guinea Defence Force.

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water. Some remain current, while many date from the 17th to 19th centuries. The word nautical derives from the Latin nauticus, from Greek nautikos, from nautēs: "sailor", from naus: "ship".