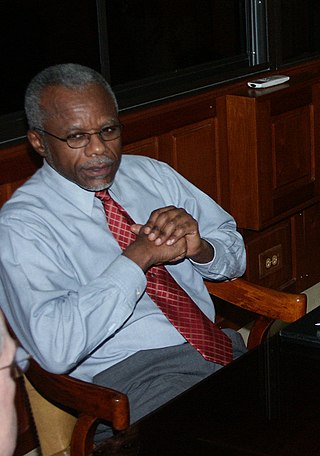

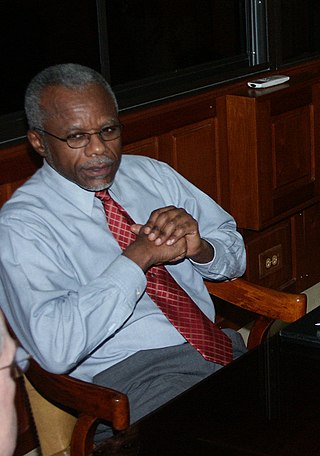

Yvon Neptune is a Haitian politician and architect who served as the Prime Minister of Haïti from 2002 to 2004. He was appointed by President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, and took office on 15 March 2002. He had previously served as President of the Senate from 2000 to 2002.

Danilo Türk is a Slovenian diplomat, professor of international law, human rights expert, and political figure who served as President of Slovenia from 2007 to 2012. He was the first Slovene ambassador to the United Nations, from 1992 to 2000, and was the UN Assistant Secretary General for Political Affairs from 2000 to 2005.

Antoine Izméry was a Haitian businessman and pro-democracy activist.

Vesna Pusić is a Croatian sociologist and politician who served as First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign and European Affairs in the centre-left cabinet of Zoran Milanović. She was Croatia's second female Foreign Minister taking the office after Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović. She is known as an outspoken liberal and an advocate of European integration, anti-fascism, gender equality and LGBT rights.

The Raboteau massacre was an incident on April 22, 1994, in which military and paramilitary forces attacked the neighborhood of Raboteau Gonaïves, Haiti, the citizens of which had been participating in pro-Jean-Bertrand Aristide demonstrations. At least 23 residents were killed, though most groups estimated the true casualties to be higher.

The United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti, also known as MINUSTAH, an acronym of the French name, was a UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti that was in operation from 2004 to 2017. The mission's military component was led by the Brazilian Army and commanded by a Brazilian. The force was composed of 2,366 military personnel and 2,533 police, supported by international civilian personnel, a local civilian staff and United Nations Volunteers.

According to its Constitution and written laws, Haiti meets most international human rights standards. In practice, many provisions are not respected. The government's human rights record is poor. Political killings, kidnapping, torture, and unlawful incarceration are common unofficial practices, especially during periods of coups or attempted coups.

Transitional justice is a process which responds to human rights violations through judicial redress, political reforms and cultural healing efforts in a region or country, and other measures in order to prevent the recurrence of human rights abuse. Transitional justice consists of judicial and non-judicial measures implemented in order to redress legacies of human rights abuses. Such mechanisms "include criminal prosecutions, truth commissions, reparations programs, and various kinds of institutional reforms" as well as memorials, apologies, and various art forms. Transitional justice is instituted at a point of political transition classically from war to positive peace, or more broadly from violence and repression to societal stability and it is informed by a society's desire to rebuild social trust, reestablish what is right from what is wrong, repair a fractured justice system, and build a democratic system of governance. Given different contexts and implementation the ability to achieve these outcomes varies. The core value of transitional justice is the very notion of justice—which does not necessarily mean criminal justice. This notion and the political transformation, such as regime change or transition from conflict are thus linked to a more peaceful, certain, and democratic future.

The Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti (IJDH) is a non-profit organization based in Boston, Massachusetts, US, that seeks to accompany the people of Haiti in their nonviolent struggle for the consolidation of constitutional democracy, justice and human rights. IJDH distributes information on human rights conditions in Haiti, pursues legal cases in Haitian, U.S. and international courts, and promotes grassroots advocacy initiatives with organizations in Haiti and abroad. IJDH was founded in the wake of the February 2004 coup d'état that overthrew Haiti's elected, constitutional government. The institute works closely with its Haitian affiliate, the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI).

Ronald Dauphin is a Haitian grassroots activist, customs worker and political prisoner who has been imprisoned without trial since March 2004. A member of Fanmi Lavalas, he was arrested by armed rebels on March 1, 2004 - the day after the controversial Haitian President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, fled into exile which was triggered by both a popular and an armed uprising. Mr. Dauphin has spent the ensuing years in a Haitian prison without having been convicted of any crime. Prior to his arrest, Ronald Dauphin A.K.A "Black" or Black Ronald, had been working several security and disposal jobs for the Lavalas party. He had also been the main security chief for the Mayor of Saint-Marc in the time prior to his government contract work. While incarcerated, his father was burned alive in his house by people seeking revenge on Ronald. He was also diagnosed with tuberculosis, due to the poor and overcrowded prison system in Haiti.

The Center for Justice and Accountability (CJA) is a US non-profit international human rights organization based in San Francisco, California. Founded in 1998, CJA represents survivors of torture and other grave human rights abuses in cases against individual rights violators before U.S. and Spanish courts. CJA has pioneered the use of civil litigation in the United States as a means of redress for survivors from around the world.

Brian Concannon, Jr. is an American human rights lawyer and foreign policy advocate. He is the Executive Director of the Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti (IJDH), which he co-founded in 2004. Concannon also serves as a member of the Editorial Board of Health and Human Rights: An International Journal at the Harvard School of Public Health, and is a contributor to the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft blog. He is an alumnus of Boston College High School'81, as well as an Ignatius Award winner. He holds an undergraduate degree from Middlebury College and JD from Georgetown Law. He is the recipient of the Wasserstein Public Interest Fellowship from Harvard Law School the Brandeis International Fellowship in Human Rights, Intervention, and International Law and an Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters from Canisius College. Brian has qualified as an expert witness on country conditions Haiti in over 40 cases in the U.S. and Canada, appearing on behalf of both applicants and the U.S. government.

The 1991 Haitian coup d'état took place on 29 September 1991, when President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, elected eight months earlier in the 1990–91 Haitian general election, was deposed by the Armed Forces of Haiti. Haitian military officers, primarily Army General Raoul Cédras, Army Chief of Staff Philippe Biamby and Chief of the National Police, Michel François led the coup. Aristide was sent into exile, his life only saved by the intervention of US, French and Venezuelan diplomats. Aristide would later return to power in 1994.

The 2010s Haiti cholera outbreak was the first modern large-scale outbreak of cholera—a disease once considered beaten back largely due to the invention of modern sanitation. The disease was reintroduced to Haiti in October 2010, not long after the disastrous earthquake earlier that year, and since then cholera has spread across the country and become endemic, causing high levels of both morbidity and mortality. Nearly 800,000 Haitians have been infected by cholera, and more than 9,000 have died, according to the United Nations (UN). Cholera transmission in Haiti today is largely a function of eradication efforts including WASH, education, oral vaccination, and climate variability. Early efforts were made to cover up the source of the epidemic, but thanks largely to the investigations of journalist Jonathan M. Katz and epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux, it is widely believed to be the result of contamination by infected United Nations peacekeepers deployed from Nepal. In terms of total infections, the outbreak has since been surpassed by the war-fueled 2016–2021 Yemen cholera outbreak, although the Haiti outbreak is still one of the most deadly modern outbreaks. After a three-year hiatus, new cholera cases reappeared in October 2022.

Angkhana Neelaphaijit, née Angkhana Wongrachen, is a Thai human rights activist, former member of the National Human Rights Commission, and the wife of disappeared human rights lawyer Somchai Neelaphaijit. Amnesty International described her as "a leading human rights defender in Southern Thailand".

The Viasna Human Rights Centre is a human rights organization based in Minsk, Belarus. The organization aims to provide financial and legal assistance to political prisoners and their families, and was founded in 1996 by activist Ales Bialatski in response to large-scale repression of demonstrations by the government of Alexander Lukashenko.

The Goldin Institute is a non-profit organization based in Chicago, Illinois, US, that works directly with communities around the globe to create their own strategies and solutions to issues such as poverty alleviation, environmental sustainability, gender empowerment and conflict resolution.

Loune Viaud is Executive Director of Zanmi Lasante, Partners in Health’s sister organization in Haiti. She won the 2002 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award for her work with the group to provide health care in Haiti, and in 2003 was named one of Ms. magazine's "Women of the Year".

Reed Brody is a Hungarian-American human rights lawyer and prosecutor. He specializes in helping victims pursue abusive leaders for atrocities, and has gained fame as the "Dictator Hunter". He was counsel for the victims in the case of the exiled former dictator of Chad, Hissène Habré – who was convicted of crimes against humanity in Senegal – and has worked with the victims of Augusto Pinochet and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. He currently works with victims of the former dictator of Gambia, Yahya Jammeh. He is author of several books including To Catch a Dictator: The Pursuit and Trial of Hissène Habré.

Haiti's National Truth and Justice Commission began its operations in April 1995 and ended in February 1996. The country's once diverse and lively civil society had been tarnished greatly as a result of the ousting of its first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, by its military forces. This deposing of President Aristide is widely known as a coup d'état, and from 1991 to 1994, the country became known for its weak civilian government. The army was determined to return Haiti to the intimidated society existing during the Duvalier dictatorship seven years prior.