Related Research Articles

A social norm is a shared standard of acceptable behavior by a group. Social norms can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into rules and laws. Social normative influences or social norms, are deemed to be powerful drivers of human behavioural changes and well organized and incorporated by major theories which explain human behaviour. Institutions are composed of multiple norms. Norms are shared social beliefs about behavior; thus, they are distinct from "ideas", "attitudes", and "values", which can be held privately, and which do not necessarily concern behavior. Norms are contingent on context, social group, and historical circumstances.

Neorealism or structural realism is a theory of international relations that emphasizes the role of power politics in international relations, sees competition and conflict as enduring features and sees limited potential for cooperation. The anarchic state of the international system means that states cannot be certain of other states' intentions and their security, thus prompting them to engage in power politics.

International relations is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns all activities among states—such as war, diplomacy, trade, and foreign policy—as well as relations with and among other international actors, such as intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs), international legal bodies, and multinational corporations (MNCs).

International relations theory is the study of international relations (IR) from a theoretical perspective. It seeks to explain behaviors and outcomes in international politics. The three most prominent schools of thought are realism, liberalism and constructivism. Whereas realism and liberalism make broad and specific predictions about international relations, constructivism and rational choice are methodological approaches that focus on certain types of social explanation for phenomena.

The national interest is a sovereign state's goals and ambitions – be it economic, military, cultural, or otherwise – taken to be the aim of its government.

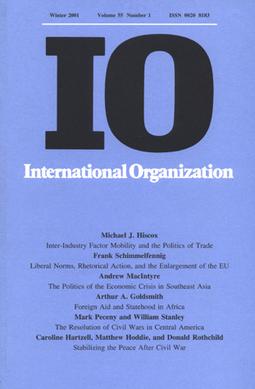

International Organization is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal that covers the entire field of international affairs. It was established in 1947 and is published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International Organization Foundation. The editors-in-chief are Brett Ashley Leeds and Layna Mosley.

Alexander Wendt is an American political scientist who is one of the core social constructivist researchers in the field of international relations, and a key contributor to quantum social science. Wendt and academics such as Nicholas Onuf, Peter J. Katzenstein, Emanuel Adler, Michael Barnett, Kathryn Sikkink, John Ruggie, Martha Finnemore, Erik Ringmar and others have, within a relatively short period, established constructivism as one of the major schools of thought in the field.

Humanitarian intervention is the use or threat of military force by a state across borders with the intent of ending severe and widespread human rights violations in a state which has not given permission for the use of force. Humanitarian interventions are aimed at ending human rights violations of individuals other than the citizens of the intervening state. Humanitarian interventions are only intended to prevent human rights violations in extreme circumstances. Attempts to establish institutions and political systems to achieve positive outcomes in the medium- to long-run, such as peacekeeping, peace-building and development aid, do not fall under this definition of a humanitarian intervention.

In international relations (IR), constructivism is a social theory that asserts that significant aspects of international relations are shaped by ideational factors. The most important ideational factors are those that are collectively held; these collectively held beliefs construct the interests and identities of actors. Constructivist scholarship in IR is rooted in approaches and theories from the field of sociology.

In international relations theory, the concept of anarchy is the idea that the world lacks any supreme authority or sovereignty. In an anarchic state, there is no hierarchically superior, coercive power that can resolve disputes, enforce law, or order the system of international politics. In international relations, anarchy is widely accepted as the starting point for international relations theory.

The English School of international relations theory maintains that there is a 'society of states' at the international level, despite the condition of anarchy. The English school stands for the conviction that ideas, rather than simply material capabilities, shape the conduct of international politics, and therefore deserve analysis and critique. In this sense it is similar to constructivism, though the English School has its roots more in world history, international law and political theory, and is more open to normative approaches than is generally the case with constructivism.

Michael Nathan Barnett is a professor of international relations at George Washington University's Elliott School of International Affairs. Known for his Constructivist approach, his scholarship and research has been in the areas of international organizations, international relations theory, and Middle Eastern politics.

Nicholas Onuf is an American scholar. Onuf is currently Professor Emeritus of International Relations at Florida International University and is on the editorial boards of International Political Sociology, Cooperation and Conflict, and Contexto Internacional. He is a constructivist scholar of international relations. He has been credited with coining the term "Constructivism."

Feminist constructivism is an international relations theory which builds upon the theory of constructivism. Feminist constructivism focuses upon the study of how ideas about gender influence global politics. It is the communication between two postcolonial theories; feminism and constructivism, and how they both share similar key ideas in creating gender equality globally.

Social Theory of International Politics is a book by Alexander Wendt. It expresses a constructivist approach to the study of international relations and is one of the leading texts within the constructivist approach to international relations scholarship.

The rationalist–constructivist debate is an ontological debate within international relations theory between rationalism and constructivism. In a 1998 article, Christian Reus-Smit and Richard Price suggested that the rationalist–constructivist debate was, or was about to become, the most significant in the discipline of international relations theory. The debate can be seen as to be centered on preference formation, with rationalist theories characterising changes in terms of shifts in capabilities, whereas constructivists focus on preference formation.

Sociological institutionalism is a form of new institutionalism that concerns "the way in which institutions create meaning for individuals." Its explanations are constructivist in nature. According to Ronald L. Jepperson and John W. Meyer, Sociological institutionalism

treats the “actorhood” of modern individuals and organizations as itself constructed out of cultural materials – and treats contemporary institutional systems as working principally by creating and legitimating agentic actors with appropriate perspectives, motives, and agendas. The scholars who have developed this perspective have been less inclined to emphasize actors’ use of institutions and more inclined to envision institutional forces as producing and using actors. By focusing on the evolving construction and reconstruction of the actors of modern society, institutionalists can better explain the dramatic social changes of the contemporary period – why these changes cut across social contexts and functional settings, and why they often become worldwide in character.

Amitav Acharya is a scholar and author, who is Distinguished Professor of International Relations at American University, Washington, D.C., where he holds the UNESCO Chair in Transnational Challenges and Governance at the School of International Service, and serves as the chair of the ASEAN Studies Initiative. Acharya has expertise in and has made contributions to a wide range of topics in International Relations, including constructivism, ASEAN and Asian regionalism, and Global International Relations. He became the first non-Western President of the International Studies Association when he was elected to the post for 2014–15.

The logic of appropriateness is a theoretical perspective to explain human decision-making. It proposes that decisions and behavior follow from rules of appropriate behavior for a given role or identity. These rules are institutionalized in social practices and sustained over time through learning. People adhere to them because they see them as natural, rightful, expected, and legitimate. In other words, the logic of appropriateness assumes that actors decide on the basis of what social norms deem right rather than what cost-benefit calculations suggest best. The term was coined by organization theorists James G. March and Johan Olsen. They presented the argument in two prominent articles published by the journals Governance in 1996 and International Organization in 1998.

Rational choice is a prominent framework in international relations scholarship. Rational choice is not a substantive theory of international politics, but rather a methodological approach that focuses on certain types of social explanation for phenomena. In that sense, it is similar to constructivism, and differs from liberalism and realism, which are substantive theories of world politics. Rationalist analyses have been used to substantiate realist theories, as well as liberal theories of international relations.

References

- ↑ As listed in Thamassat University library catalog Archived 2015-05-06 at the Wayback Machine .

- ↑ Announced Nov. 21, 2011.

- 1 2 Jordan, Richard; Maliniak, Daniel; Oakes, Amy; Peterson, Susan; Tierney, Michael J. (2009), One Discipline or Many? TRIP Survey of International Relations Faculty in Ten Countries (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-07-11. For 2014 results that if anything ranked her even more highly see 2014 FP Ivory Tower Survey., 3 January 2012

- ↑ Price, Richard; Reus-Smit, Chrustian (1998). "Dangerous Liaisons?". European Journal of International Relations. 4 (3): 259–294. doi:10.1177/1354066198004003001. ISSN 1354-0661. S2CID 144450112.

- ↑ Checkel, Jeffrey T. (2014), Bennett, Andrew; Checkel, Jeffrey T. (eds.), "Mechanisms, process, and the study of international institutions", Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool, Strategies for Social Inquiry, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 75–76, ISBN 978-1-107-04452-4

- ↑ Pouliot, Vincent (2004). "The essence of constructivism". Journal of International Relations and Development. 7 (3): 319–336. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800022. ISSN 1408-6980. S2CID 7659893.

- 1 2 Dessler, David (1997). "Book Reviews: National Interests in International Society.By Martha Finnemore". American Journal of Sociology. 103 (3): 785–786. doi:10.1086/231265. ISSN 0002-9602. S2CID 151346679.

- ↑ International Relations Theory and the Asia-Pacific. Columbia University Press. 2003. p. 113. JSTOR 10.7312/iken12590.

- ↑ Finnemore's web page at GWU.

- ↑ Entry for her thesis, "Science, the state, and international society" Archived 2012-02-23 at the Wayback Machine , in the Stanford library system.

- ↑ Finnemore, Martha (2003). The Purpose of Intervention: Changing Beliefs About the Use of Force. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3845-5. JSTOR 10.7591/j.ctt24hg32.

- ↑ Dessler, David; Owen, John (2005). "Constructivism and the Problem of Explanation: A Review Article". Perspectives on Politics. 3 (03): 597–610. doi:10.1017/S1537592705050371. ISSN 1537-5927. JSTOR 3689039. S2CID 145089464.

- ↑ Blyth, Mark; Helgadottir, Oddny; Kring, William (2016-03-17). Fioretos, Orfeo; Falleti, Tulia G; Sheingate, Adam (eds.). "Ideas and Historical Institutionalism". The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199662814.001.0001. ISBN 9780199662814 . Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ↑ Barnett, Michael; Finnemore, Martha (2012). Rules for the World. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9780801465161. ISBN 978-0-8014-6516-1.

- ↑ Ege, Jörn (2020-11-23). "What International Bureaucrats (Really) Want: Administrative Preferences in International Organization Research". Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations. 26 (4): 577–600. doi: 10.1163/19426720-02604003 . hdl: 11475/26277 . ISSN 1942-6720.

- ↑ "International Organization | Most cited". Cambridge Core. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ↑ Sandholtz, Wayne (2017-06-28). International Norm Change. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.588. ISBN 9780190228637.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Snyder, Jack (2003). "Is" and "Ought": Evaluating Empirical Aspects of Normative Research. MIT Press. p. 371. ISBN 0-262-05068-4. OCLC 50422990.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Owen IV, John (2010). The Clash of Ideas in World Politics. Princeton University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-691-14239-5.

- ↑ Peterson, Susan; Tierney, Michael J.; Maliniak, Daniel (2005), Teaching and Research Practices, Views on the Discipline, and Policy Attitudes of International Relations Faculty at U.S. Colleges and Universities (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-16.

- ↑ Article on election to AAAS [ permanent dead link ].

- ↑ Review by Rob Dixon in Millennium26: 170 (1997), doi : 10.1177/03058298970260010313.

- ↑ Review by David Dessler in American Journal of Sociology103: 785–786 (1997), doi : 10.1086/231265.

- ↑ Review by Ted Hopf in American Political Science Review 93: 752–754 (1999), doi : 10.2307/2585645.

- ↑ Review by Simon Collard-Wexler in Millennium33: 183 (2004), doi : 10.1177/03058298040330010906.

- ↑ Review by Georg Nolte in European Journal of International Law16: 167–169 (2005), doi : 10.1093/ejil/chi113.

- ↑ Review by Richard Ned Lebow in Journal of Cold War Studies8: 148–149 (1006), doi : 10.1162/jcws.2006.8.1.148.

- 1 2 GWU Elliott School Professor Finnemore Awarded for her Rules of the World, GWU, November 29, 2005.

- ↑ Woodrow Wilson Foundation Award Archived 2015-05-18 at the Wayback Machine , APSA.

- ↑ Review by Michelle Egan in Millennium34: 591 (2006), doi : 10.1177/03058298060340021703.

- ↑ Review by Pepper D. Culpepper in Perspectives on Politics4: 623–625 (2006), doi : 10.1017/S1537592706670369.

- ↑ Review by Jacob Katz Cogan in The American Journal of International Law100: 278–281 (2006), doi : 10.2307/3518865.

- ↑ Review by Paul F. Diehl in Journal of Cold War Studies9: 129–130 (2007), doi : 10.1162/jcws.2007.9.4.129.