Related Research Articles

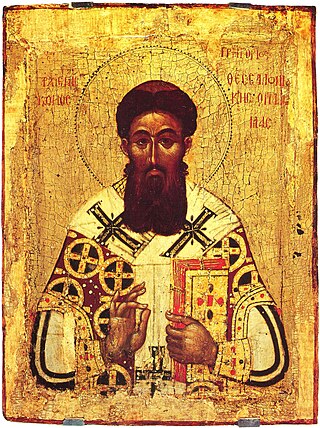

Gregory Palamas was a Byzantine Greek theologian and Eastern Orthodox cleric of the late Byzantine period. A monk of Mount Athos and later archbishop of Thessaloniki, he is famous for his defense of hesychast spirituality, the uncreated character of the light of the Transfiguration, and the distinction between God's essence and energies. His teaching unfolded over the course of three major controversies, (1) with the Italo-Greek Barlaam between 1336 and 1341, (2) with the monk Gregory Akindynos between 1341 and 1347, and (3) with the philosopher Gregoras, from 1348 to 1355. His theological contributions are sometimes referred to as Palamism, and his followers as Palamites.

Gennadius II was a Byzantine Greek philosopher and theologian, and Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 1454 to 1464. He was a strong advocate for the use of Aristotelian philosophy in the Orthodox Church.

Barlaam of Seminara, c. 1290–1348, or Barlaam of Calabria was a Basilian monk, theologian and humanistic scholar born in southern Italy. He was a scholar and clergyman of the 14th century, as well as a humanist, philologist and theologian.

Mark of Ephesus was a hesychast theologian of the late Palaiologan period of the Byzantine Empire who became famous for his rejection of the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438–1439). As a monk in Constantinople, Mark was a prolific hymnographer and a follower of Gregory Palamas' theological views. As a theologian and a scholar, he was instrumental in the preparations for the Council of Ferrara-Florence, and as Metropolitan of Ephesus and delegate for the Patriarch of Alexandria, he was one of the most important voices at the synod. After renouncing the council as a lost cause, Mark became the leader of the Orthodox opposition to the Union of Florence, thus sealing his reputation as a defender of Eastern Orthodoxy and pillar of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Jeremias II Tranos was Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople three times between 1572 and 1595.

In Eastern Orthodox (palamite) theology, there is a distinction between the essence (ousia) and the energies (energeia) of God. It was formulated by Gregory Palamas (1296–1359) as part of his defense of the Athonite monastic practice of Hesychasm against the charge of heresy brought by the humanist scholar and theologian Barlaam of Calabria.

Kallistos I was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople for two periods from June 1350 to 1353 and from 1354 to 1363. Kallistos I was an Athonite monk and supporter of Gregory Palamas. He died in Constantinople in 1363.

The Pontifical Oriental Institute, also known as the Orientale, is a Catholic institution of higher education located in Rome and focusing on Eastern Christianity.

Demetrios Kydones, Latinized as Demetrius Cydones or Demetrius Cydonius, was a Byzantine Greek theologian, translator, author and influential statesman, who served an unprecedented three terms as Mesazon of the Byzantine Empire under three successive emperors: John VI Kantakouzenos, John V Palaiologos and Manuel II Palaiologos.

In Eastern Orthodox Christian theology, the Tabor Light is the light revealed on Mount Tabor at the Transfiguration of Jesus, identified with the light seen by Paul at his conversion.

Palamism or the Palamite theology comprises the teachings of Gregory Palamas, whose writings defended the Eastern Orthodox practice of Hesychasm against the attack of Barlaam. Followers of Palamas are sometimes referred to as Palamites.

John Kyparissiotes or Cyparissiotes, called “the Wise” by his contemporaries, was a Byzantine theologian and the leading Anti-Palamite writer in the period that followed the deaths of Nikephoros Gregoras and of Palamas himself. Of all the fourteenth-century opponents of Gregory Palamas, he was the most systematic theologian, and perhaps the ablest. Most of his works remain in original manuscripts, unedited; none has ever appeared in translation in a modern language. Although editions of some of his works have been made since the 1950s, most of them, published in small printings in Greece, are nearly as difficult to come by in the West as the original manuscripts themselves.

The Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church have been in a state of official schism from one another since the East–West Schism of 1054. This schism was caused by historical and language differences, and the ensuing theological differences between the Western and Eastern churches.

Dositheus II Notaras of Jerusalem was the Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Jerusalem between 1669 and 1707 and a theologian of the Eastern Orthodox Church. He was known for standing against influences of the Roman Catholic and Protestant churches. He convened the Synod of Jerusalem to counter the Calvinist confessions of Cyril Lucaris.

The Hesychast controversy was a theological dispute in the Byzantine Empire during the 14th century between supporters and opponents of Gregory Palamas. While not a primary driver of the Byzantine Civil War, it influenced and was influenced by the political forces in play during that war. The dispute concluded with the victory of the Palamists and the inclusion of Palamite doctrine as part of the dogma of the Eastern Orthodox Church as well as the canonization of Palamas.

20th century Eastern Orthodox theology has been dominated by neo-Palamism, the revival of St. Palamas and hesychasm. John Behr characterizes Eastern Orthodox theology as having been "reborn in the twentieth century." Norman Russell describes Eastern Orthodox theology as having been dominated by an "arid scholasticism" for several centuries after the fall of Constantinople. Russell describes the postwar re-engagement of modern Greek theologians with the Greek Fathers, which occurred with the help of diaspora theologians and Western patristic scholars. A significant component of this re-engagement with the Greek Fathers has been a rediscovery of Palamas by Greek theologians; Palamas had previously been given less attention than the other Fathers.

Manuel Kalekas was a monk and theologian of the Byzantine Empire.

Anthimus II was Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople for a few months in 1623.

Gregorios Papamichael (1875–1956) was a theologian of the Orthodox Church of Greece and a renowned professor at the Theology School of the University of Athens.

Aurelio Palmieri was an Italian priest and scholar. He joined the Augustinians by 1885 but was later laicized. His main focus was theology, history of Christianity, Byzantine studies and eastern Christianity. Palmieri worked for some years at the Congress Library and from 1922 until his death was the director of the Slavonic section of the Institute for Oriental Europe in Italy. He wrote 15 books and hundreds of articles, and also translated literary works of Russian and polish authors. His most significant works are the Russian Church and Dogmatic Orthodox Theology.

References

- ↑ "Fr. Martin Jugie, A.A. (1878-1954)". assumptio.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Martin (Etienne) JUGIE - 1878-1954".

- ↑ Norman Russell, Gregory Palamas and the Making of Palamism in the Modern Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), p. 45

- 1 2 3 Russell, Making of Palamism, p. 45.

- ↑ Martin Jugie, "Grégoire Palamas et la controverse palamite," in Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, Vol. 11(2) (Paris: Letouzey et Ané, 1932), cols. 1735-1818;

- ↑ Martin Jugie, Theologia dogmatica Christianorum Orientalium ab Ecclesia catholica dissidentium, 5 Vols. (Paris: Letouzey et Ané, 1926–1935).

- ↑ Louis Petit, Xenophon Sidéridès, Martin Jugie, eds., Oeuvres Complètes de Georges Scholarios, 8 vols. (Paris: Maison de la bonne presse, 1928-36)