Related Research Articles

Thomas Dartmouth Rice was an American performer and playwright who performed in blackface and used African American vernacular speech, song and dance to become one of the most popular minstrel show entertainers of his time. He is considered the "father of American minstrelsy". His act drew on aspects of African American culture and popularized them with a national, and later international, audience.

"Jump Jim Crow". often shorted to just "Jim Crow", is a song and dance from 1828 that was done in blackface by white minstrel performer Thomas Dartmouth "Daddy" Rice. The song is speculated to have been taken from Jim Crow, a physically disabled enslaved African-American, who is variously claimed to have lived in St. Louis, Cincinnati, or Pittsburgh. The song became a 19th-century hit and Rice performed it all over the United States as "Daddy Pops Jim Crow".

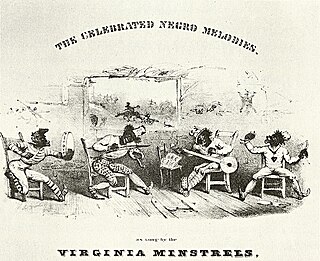

The minstrel show, also called minstrelsy, was an American form of theater developed in the early 19th century. The shows were performed by mostly white actors wearing blackface make-up for the purpose of comically portraying racial stereotypes of African-Americans by playing the role of black minstrels. There were also some African-American performers and black-only minstrel groups that formed and toured. Minstrel shows stereotyped blacks as dim-witted, lazy, buffoonish, cowardly, superstitious, and happy-go-lucky. Each show consisted of comic skits, variety acts, dancing, and music performances that depicted people specifically of African descent.

Master Juba was an African-American dancer active in the 1840s. He was one of the first black performers in the United States to play onstage for white audiences and the only one of the era to tour with a white minstrel group. His real name was believed to be William Henry Lane, and he was also known as "Boz's Juba" following Dickens's graphic description of him in American Notes.

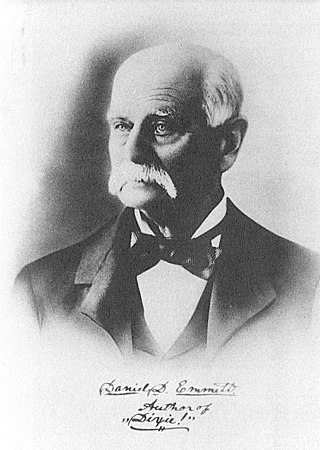

Daniel Decatur Emmett was an American composer, entertainer, and founder of the first troupe of the blackface minstrel tradition, the Virginia Minstrels. He is most remembered as the composer of the song "Dixie".

"Dixie", also known as "Dixie's Land", "I Wish I Was in Dixie", and other titles, is a song about the Southern United States first made in 1859. It is one of the most distinctively Southern musical products of the 19th century. It was not a folk song at its creation, but it has since entered the American folk vernacular. The song likely cemented the word "Dixie" in the American vocabulary as a nickname for the Southern U.S.

"Old Dan Tucker," also known as "Ole Dan Tucker," "Dan Tucker," and other variants, is an American popular song. Its origins remain obscure; the tune may have come from oral tradition, and the words may have been written by songwriter and performer Dan Emmett. The blackface troupe the Virginia Minstrels popularized "Old Dan Tucker" in 1843, and it quickly became a minstrel hit, behind only "Miss Lucy Long" and "Mary Blane" in popularity during the antebellum period. "Old Dan Tucker" entered the folk vernacular around the same time. Today it is a bluegrass and country music standard. It is no. 390 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

The Ethiopian Serenaders was an American blackface minstrel troupe successful in the 1840s and 1850s. Through various line-ups they were managed and directed by James A. Dumbolton (c.1808–?), and are sometimes mentioned as the Boston Minstrels, Dumbolton Company or Dumbolton's Serenaders.

The Padlock is a two-act 'afterpiece' opera by Charles Dibdin. The text was by Isaac Bickerstaffe. It debuted in 1768 at the Drury Lane Theatre in London as a companion piece to The Earl of Warwick. It partnered other plays before a run of six performances in tandem with The Fatal Discovery by John Home. "The Padlock" was a success, largely due to Dibdin's portrayal of Mungo, a blackface caricature of a black servant from the West Indies. The company took the production to the United States the next year, where a portrayal by Lewis Hallam, Jr. as Mungo met with even greater accolades. The libretto was first published in London around 1768 and in Dublin in 1775. The play remained in regular circulation in the U.S. as late as 1843. It was revived by the Old Vic Company in London and on tour in the UK in 1979 in a new orchestration by Don Fraser and played in a double-bill with Garrick's Miss In Her Teens. The role of Mungo was, again, played by a white actor. Opera Theatre of Chicago have recently revived the piece (2007?) where, it would seem, the role of Mungo was changed to that of an Irish servant.

Bryant's Minstrels was a blackface minstrel troupe that performed in the mid-19th century, primarily in New York City. The troupe was led by the O'Neill brothers from upstate New York, who took the stage name Bryant.

"Coal Black Rose" is a folk song, one of the earliest songs to be sung by a man in blackface. The man dressed as an overweight and overdressed black woman, who was found unattractive and masculine-looking. The song was first performed in the United States in the late 1820s, possibly by George Washington Dixon. It was certainly Dixon who popularized the song when he put on three blackface performances at the Bowery Theatre, the Chatham Garden Theatre, and the Park Theatre in late July 1829. These shows also propelled Dixon to stardom.

Buckley's Serenaders was a family troupe of English-born American blackface minstrels, established under that name in 1853 by James Buckley. They became one of the two most popular companies in the U.S. from the mid-1850s to the 1860s, the other being the Christy and Wood Minstrels.

"Clare de Kitchen" is an American song from the blackface minstrel tradition. It dates to 1832, when blackface performers such as George Nichols, Thomas D. Rice, and George Washington Dixon began to sing it. These performers and American writers such as T. Allston Brown traced the song's origins to black riverboatsmen. "Clare de Kitchen" became very popular, and performers sometimes sang the lyrics of "Blue Tail Fly" to its tune.

"De Wild Goose-Nation" is an American song composed by blackface minstrel performer Dan Emmett.

"Ole Bull and Old Dan Tucker" is a traditional American song. Several different versions are known, the earliest published in 1844 by the Boston-based Charles Keith company. The song's lyrics tell of the rivalry and contest of skill between Ole Bull and Dan Tucker. The song also satirizes the low pay earned by early minstrel performers: "Ole Bull come to town one day [and] got five hundred for to play."

"Walk Along John", also known as "Oh, Come Along John", is an American song written for the blackface minstrel show stage in 1843. The lyrics of the song are typical of those of the early minstrel show. They are largely nonsense about a black man who boasts about his exploits.

"Miss Lucy Long", also known as "Lucy Long" as well as by other variants, is an American song that was popularized in the blackface minstrel show.

Francis Marion Brower was an American blackface performer active in the mid-19th century. Brower began performing blackface song-and-dance acts in circuses and variety shows when he was 13. He eventually introduced the bones to his act, helping to popularize it as a blackface instrument. Brower teamed with various other performers, forming his longest association with banjoist Dan Emmett beginning in 1841. Brower earned a reputation as a gifted dancer. In 1842, Brower and Emmett moved to New York City. They were out of work by January 1843, when they teamed up with Billy Whitlock and Richard Pelham to form the Virginia Minstrels. The group was the first to perform a full minstrel show as a complete evening's entertainment. Brower pioneered the role of the endman.

John Diamond, aka Jack or Johnny, was an Irish-American dancer and blackface minstrel performer. Diamond entered show business at age 17 and soon came to the attention of circus promoter P. T. Barnum. In less than a year, Diamond and Barnum had a falling-out, and Diamond left to perform with other blackface performers. Diamond's dance style merged elements of English, Irish, and African dance. For the most part, he performed in blackface and sang popular minstrel tunes or accompanied a singer or instrumentalist. Diamond's movements emphasized lower-body movements and rapid footwork with little movement above the waist.

References

- Mahar, William J. (1999). Behind the Burnt Cork Mask: Early Blackface Minstrelsy and Antebellum American Popular Culture. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.