Related Research Articles

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word anagram itself can be rearranged into nag a ram; which is an Easter egg in Google when searching for the word "anagram"; the word binary-into brainy and the word adobe-into abode.

Sir Philip Sidney was an English poet, courtier, scholar and soldier who is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan age. His works include a sonnet sequence, Astrophel and Stella, a treatise, The Defence of Poesy and a pastoral romance, The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1716.

George Puttenham (1529–1590) was an English writer and literary critic. He is generally considered to be the author of the influential handbook on poetry and rhetoric, The Arte of English Poesie (1589).

Sir John Davies was an English poet, lawyer, and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1597 and 1621. He became Attorney General for Ireland and formulated many of the legal principles that underpinned the British Empire.

William Alexander, 1st Earl of Stirling was a Scottish courtier and poet who was involved in the Scottish colonisation of Charles Fort, later Port-Royal, Nova Scotia in 1629 and Long Island, New York. His literary works include Aurora (1604), The Monarchick Tragedies (1604) and Doomes-Day.

Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke was among the first Englishwomen to gain notice for her poetry and her literary patronage. By the age of 39, she was listed with her brother Philip Sidney and with Edmund Spenser and William Shakespeare among the notable authors of the day in John Bodenham's verse miscellany Belvidere. Her play Antonius is widely seen as reviving interest in soliloquy based on classical models and as a likely source of Samuel Daniel's closet drama Cleopatra (1594) and of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra (1607). She was also known for translating Petrarch's "Triumph of Death", for the poetry anthology Triumphs, and above all for a lyrical, metrical translation of the Psalms.

Lady Mary Wroth was an English noblewoman and a poet of the English Renaissance. A member of a distinguished literary family, Lady Wroth was among the first female English writers to have achieved an enduring reputation. Mary Wroth was niece to Mary Herbert née Sidney, and to Sir Philip Sidney, a famous Elizabethan poet-courtier.

Sir Francis Throckmorton was a conspirator against Queen Elizabeth I of England in the Throckmorton Plot.

Anne Killigrew (1660–1685) was an English poet and painter, described by contemporaries as "A Grace for beauty, and a Muse for wit." Born in London, she and her family were active in literary and court circles. Killigrew's poems were circulated in manuscript and collected and published posthumously in 1686 after she died from smallpox at age 25. They have been reprinted several times by modern scholars, most recently and thoroughly by Margaret J. M. Ezell.

Rachel Speght was a poet and polemicist. She was the first Englishwoman to identify herself, by name, as a polemicist and critic of gender ideology. Speght, a feminist and a Calvinist, is perhaps best known for her tract A Mouzell for Melastomus. It is a prose refutation of Joseph Swetnam's misogynistic tract, The Arraignment of Lewd, Idle, Froward, and Unconstant Women, and a significant contribution to the Protestant discourse of biblical exegesis, defending women's nature and the worth of womankind. Speght also published a volume of poetry, Mortalities Memorandum with a Dreame Prefixed, a Christian reflection on death and a defence of the education of women.

William Fowler was a Scottish poet or makar, writer, courtier and translator.

Mary Anne Atwood was an English writer on hermeticism and spiritual alchemy.

Elizabeth Melville, Lady Culross (c.1578–c.1640) was a Scottish poet.

Ester Sowernam is the pseudonymous author of one of the first defences of women published in England and a participant in the Swetnam Controversy of 1615–20.

Walter Quin (1575?–1640) was an Irish poet who worked in Scotland and England for the House of Stuart.

Katherine Stubbes, or Stubbs, was an Englishwoman, best known for being the subject of a biography and memorial tract called A Chrystall Glasse for Christian Women, written and published by her husband Philip Stubbs after her death. Besides details about her parents, marriage, and conduct as a daughter and wife, the work also records the confessions of faith that she spoke before her death. It also includes her dying farewells to family and friends. The text ends with her dying greetings to Christ.

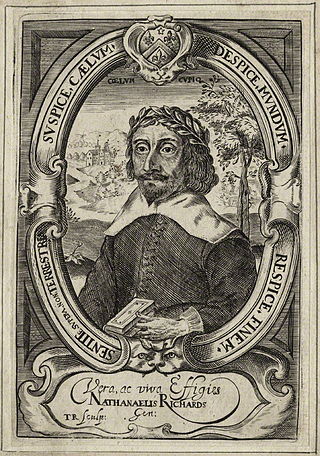

Nathanael Richards was an English dramatist and poet, perhaps from Kent. He should not be confused with Nathaniel Richards (1611–1660), a cleric.

The Lamentation of a Sinner is a three-part sequence of reflections published by the English queen Catherine Parr, the sixth wife and widow of Henry VIII, as well as the first woman to publish in English under her own name. It was written in the autumn of 1546 at the latest and published in November 1547, after her husband's death. Its publication was sponsored by the Duchess of Suffolk and the Marquess of Northampton, the Queen's closest friend and only brother respectively.

Mary Gunter born Mary Cresswell (1586–1622) was an English Catholic ward and servant who became a celebrated convert to Protestantism. She had become the ward of a man who was executed for his part in a rebellion and was then adopted by his widow. She was subjected to a rigorous conversion after she planned to be a nun. Her husband later published the sermon of her funeral and her biography which went to three editions and it was reprinted as that of an "eminent person" sixty years later.

References

- 1 2 "Mary Fage Composes Anagrams." Female and Male Voices in Early Modern England. Ed. Betty S. Travitsky and Anne Lake Prescott. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. 277–282. Print.

- ↑ Fage, Mary. "Fames Roule." The Early Modern Englishwoman: A Facsimile Library of Essential Works, Series I, Printed Writings, 1500–1640: Part 2, Volume II, The Poets, II: Mary Fage. Ed. Betty S. Travitsky and Patrick Cullen. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2000. Print.

- 1 2 3 Travitsky, Betty S. Introduction. The Early Modern Englishwoman: A Facsimile Library of Essential Works, Series I, Printed Writings, 1500–1640: Part 2, Volume II, The Poets, II: Mary Fage. Ed. Betty S. Travitsky and Patrick Cullen. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2000. Print.

- 1 2 3 4 Travitsky, Betty S. "Relations of Power, Relations to Power, and Power(ful) Relations: Mary Fage, Robert Fage, and Fames Roule." Pilgrimage for Love: Essays in Early Modern Literature in Honor of Josephine A. Roberts. Ed. Sigrid King. Tempe: Arizona State University, 1999. Print.

- ↑ Puttenham, George. The Arte of English Poesie. 1589. Ed. Gladys Doidge Willcock and Alice Walker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1936.

- ↑ Ezell, Margaret J. M. The Patriarch's Wife: Literary Evidence and the History of the Family. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1987. Print.

- ↑ De Haas, Rebecca, and Frances Teague. "Defences of Women." A Companion to Early Modern Women’s Writing. Ed. Anita Pacheco. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2002. Print.

- ↑ "Charles I (r. 1625 – 1649)." The Official Website of the British Monarchy. 2010. Web. http://www.royal.uk