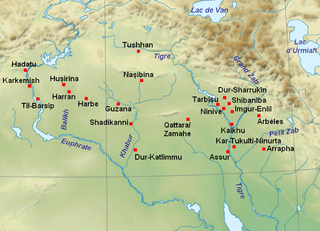

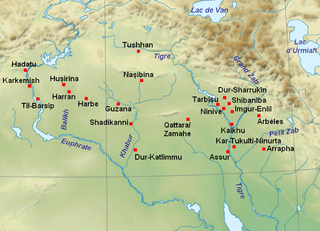

Nineveh, also known in early modern times as Kouyunjik, was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul in northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern bank of the Tigris River and was the capital and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as the largest city in the world for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country's Nineveh Governorate takes its name from it.

This article concerns the period 889 BC – 880 BC.

Shalmaneser III was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Ashurnasirpal II in 859 BC to his own death in 824 BC.

Ninurta (Sumerian: 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒅁: DNIN.URTA, possible meaning "Lord [of] Barley"), also known as Ninĝirsu (Sumerian: 𒀭𒎏𒄈𒋢: DNIN.ĜIR2.SU, meaning "Lord [of] Girsu"), is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with farming, healing, hunting, law, scribes, and war who was first worshipped in early Sumer. In the earliest records, he is a god of agriculture and healing, who cures humans of sicknesses and releases them from the power of demons. In later times, as Mesopotamia grew more militarized, he became a warrior deity, though he retained many of his earlier agricultural attributes. He was regarded as the son of the chief god Enlil and his main cult center in Sumer was the Eshumesha temple in Nippur. Ninĝirsu was honored by King Gudea of Lagash (ruled 2144–2124 BC), who rebuilt Ninĝirsu's temple in Lagash. Later, Ninurta became beloved by the Assyrians as a formidable warrior. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) built a massive temple for him at Kalhu, which became his most important cult center from then on.

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, 30 kilometres (20 mi) south of the city of Mosul, and 5 kilometres (3 mi) south of the village of Selamiyah, in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a major Assyrian city between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC. The city is located in a strategic position 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of the point that the river Tigris meets its tributary the Great Zab. The city covered an area of 360 hectares. The ruins of the city were found within one kilometre (1,100 yd) of the modern-day Assyrian village of Noomanea in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a black limestone Neo-Assyrian sculpture with many scenes in bas-relief and inscriptions. It comes from Nimrud, in northern Iraq, and commemorates the deeds of King Shalmaneser III. It is on display at the British Museum in London, and several other museums have cast replicas.

Ashur-nasir-pal II was king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BC. Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II. His son and successor was Shalmaneser III and his queen was Mullissu-mukannišat-Ninua.

National Museums Scotland is an executive non-departmental public body of the Scottish Government. It runs the national museums of Scotland.

Balawat is an archaeological site of the ancient Assyrian city of Imgur-Enlil, and modern village in Nineveh Province (Iraq). It lies 25 kilometres (16 mi) southeast from the city of Mosul and 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) to the south of the modern Assyrian town of Bakhdida.

The Department of the Middle East, numbering some 330,000 works, forms a significant part of the collections of the British Museum, and the world's largest collection of Mesopotamian antiquities outside Iraq. The collections represent the civilisations of the ancient Near East and its adjacent areas.

Winged genie is the conventional term for a recurring motif in the iconography of Assyrian sculpture. Winged genies are usually bearded male figures sporting birds' wings. The Genii are a reappearing trait in ancient Assyrian art, and are displayed most prominently in palaces or places of royalty. The two most notable places where the genies existed were Ashurnasirpal II’s palace Kalhu and Sargon II’s palace Dur-Sharrukin.

The Nimrud ivories are a large group of small carved ivory plaques and figures dating from the 9th to the 7th centuries BC that were excavated from the Assyrian city of Nimrud during the 19th and 20th centuries. The ivories mostly originated outside Mesopotamia and are thought to have been made in the Levant and Egypt, and have frequently been attributed to the Phoenicians due to a number of the ivories containing Phoenician inscriptions. They are foundational artefacts in the study of Phoenician art, together with the Phoenician metal bowls, which were discovered at the same time but identified as Phoenician a few years earlier. However, both the bowls and the ivories pose a significant challenge as no examples of either – or any other artefacts with equivalent features – have been found in Phoenicia or other major colonies.

The Statue of Ashurnasirpal II is a rare example of Assyrian sculpture in the round that was found in the mid nineteenth century at the ancient site of Kalhu by the famous archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. Dating from 883–859 BC, the statue has long been admired for its flawless condition and the high quality of its craftsmanship. It has been part of the British Museum's collection since 1851.

The Stela of Ashurnasirpal II is an enormous Assyrian monolith that was erected during the reign of Ashurnasirpal II. The stela was discovered in the mid nineteenth century at the ancient site of Kalhu by the famous British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard. Dated to between 883-859 BC, the sculpture is now part of the British Museum's collection.

The Stela of Shamshi-Adad V is a large Assyrian monolith erected during the reign of Shamshi-Adad V. The stela was discovered in the mid nineteenth century at the ancient site of Kalhu by the British archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam. Dated to between 824-811 BC, the sculpture is now part of the British Museum's collection of Middle East antiquities.

The Rotherwas Room is an English Jacobean room currently in the Mead Art Museum, in Amherst College.

Assyrian sculpture is the sculpture of the ancient Assyrian states, especially the Neo-Assyrian Empire of 911 to 612 BC, which was centered around the city of Assur in Mesopotamia which at its height, ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as portions of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia. It forms a phase of the art of Mesopotamia, differing in particular because of its much greater use of stone and gypsum alabaster for large sculpture.

The royal Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal is shown on a famous group of Assyrian palace reliefs from the North Palace of Nineveh that are now displayed in room 10a of the British Museum. They are widely regarded as "the supreme masterpieces of Assyrian art". They show a formalized ritual "hunt" by King Ashurbanipal in an arena, where captured Asian lions were released from cages for the king to slaughter with arrows, spears, or his sword. They were made about 645–635 BC, and originally formed different sequences placed around the palace. They would probably originally have been painted, and formed part of a brightly coloured overall decor.

The Queens' Tombs at Nimrud are a set of four tombs discovered by Muzahim Hussein at the site of what was once the ancient Assyrian city of Nimrud. Once the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Nimrud was located on the East bank of the Tigris river, in what would be modern day Northern Iraq. Nimrud became the second capital of the Assyrian empire during the ninth century BCE, under Assurnasirpal II. Assurnasirpal II expanded the city and built one of the most significant architectural achievements at Nimrud, the Northwest Palace––bētānu in Assyrian. The palace was the first of many built by Neo-Assyrian rulers, and it became a template for later palaces. During an excavation of the Northwest Palace in 1988, the Queen's Tombs were discovered under the Southern, domestic wing. All four tombs discovered within the palace were built during the ninth and eighth centuries and were primarily constructed of the mudbrick, baked brick, and limestone ––materials commonly used in Mesopotamian architecture. The architecture of the tombs as well as the Northwest Palace within which they are housed provide historical insight into the Assyrian Empire's building techniques. The most notable items found within the queens' tombs included hundreds of pieces of fine jewelry, pottery, clothing, and tablets. These objects crafted by Neo-Assyrian artists would later allow archaeologists to build on their understanding of Neo-Assyrian goldsmithing techniques. Each tomb was built in advance of a queen's death and construction began as early as the 9th century under Assurnasirpal II and continued under Shalmaneser III.

Phoenician metal bowls are approximately 90 decorative bowls made in the 7th–8th centuries BCE from bronze, silver and gold, found since the mid-19th century in the Eastern Mediterranean and Iraq. They were historically attributed to the Phoenicians, but are today considered to have been made by a broader group of Levantine peoples.