Monte Albán is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site in the Santa Cruz Xoxocotlán Municipality in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. The site is located on a low mountainous range rising above the plain in the central section of the Valley of Oaxaca, where the latter's northern Etla, eastern Tlacolula, and southern Zimatlán and Ocotlán branches meet. The present-day state capital Oaxaca City is located approximately 9 km (6 mi) east of Monte Albán.

Mesoamerican chronology divides the history of prehispanic Mesoamerica into several periods: the Paleo-Indian ; the Archaic, the Preclassic or Formative (2500 BCE – 250 CE), the Classic (250–900 CE), and the Postclassic (900–1521 CE); as well as the post European contact Colonial Period (1521–1821), and Postcolonial, or the period after independence from Spain (1821–present).

Mesoamerican languages are the languages indigenous to the Mesoamerican cultural area, which covers southern Mexico, all of Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The area is characterized by extensive linguistic diversity containing several hundred different languages and seven major language families. Mesoamerica is also an area of high linguistic diffusion in that long-term interaction among speakers of different languages through several millennia has resulted in the convergence of certain linguistic traits across disparate language families. The Mesoamerican sprachbund is commonly referred to as the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area.

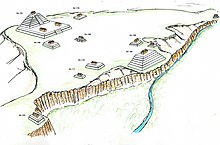

Mesoamerican pyramids form a prominent part of ancient Mesoamerican architecture. Although similar in some ways to Egyptian pyramids, these New World structures have flat tops and stairs ascending their faces, more similar to ancient Mesopotamian Ziggurats. The largest pyramid in the world by volume is the Great Pyramid of Cholula, in the east-central Mexican state of Puebla. The builders of certain classic Mesoamerican pyramids have decorated them copiously with stories about the Hero Twins, the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl, Mesoamerican creation myths, ritualistic sacrifice, etc. written in the form of Maya script on the rises of the steps of the pyramids, on the walls, and on the sculptures contained within.

Cuicuilco is an important archaeological site located on the southern shore of Lake Texcoco in the southeastern Valley of Mexico, in what is today the borough of Tlalpan in Mexico City.

San José Mogote is a pre-Columbian archaeological site of the Zapotec, a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in the region of what is now the Mexican state of Oaxaca. A forerunner to the better-known Zapotec site of Monte Albán, San José Mogote was the largest and most important settlement in the Valley of Oaxaca during the Early and Middle Formative periods of Mesoamerican cultural development.

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area that begins in the southern part of North America and extends to the Pacific coast of Central America, thus comprising the lands of central and southern Mexico, all of Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and parts of Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica. As a cultural area, Mesoamerica is defined by a mosaic of cultural traits developed and shared by its indigenous cultures.

The geography of Mesoamerica describes the geographic features of Mesoamerica, a culture area in the Americas inhabited by complex indigenous pre-Columbian cultures exhibiting a suite of shared and common cultural characteristics. Several well-known Mesoamerican cultures include the Olmec, Teotihuacan, the Maya, the Aztec and the Purépecha. Mesoamerica is often subdivided in a number of ways. One common method, albeit a broad and general classification, is to distinguish between the highlands and lowlands. Another way is to subdivide the region into sub-areas that generally correlate to either culture areas or specific physiographic regions.

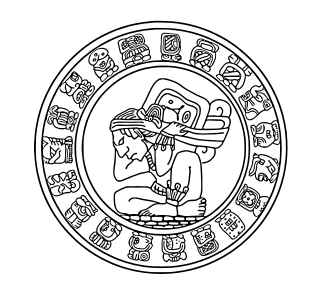

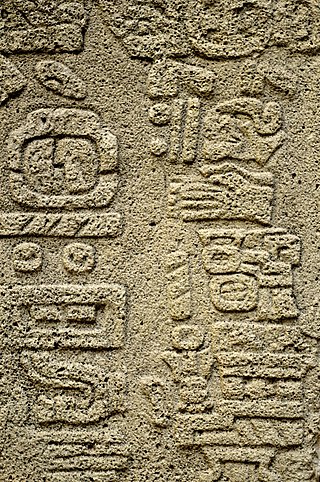

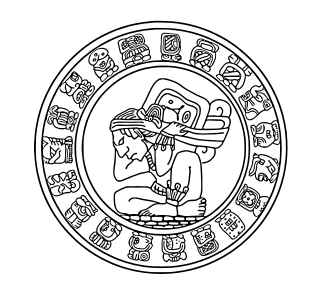

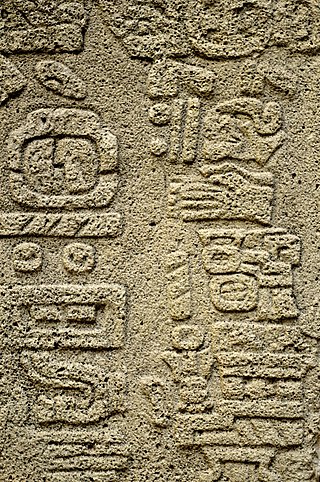

Mesoamerica, along with Mesopotamia and China, is one of three known places in the world where writing is thought to have developed independently. Mesoamerican scripts deciphered to date are a combination of logographic and syllabic systems. They are often called hieroglyphs due to the iconic shapes of many of the glyphs, a pattern superficially similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs. Fifteen distinct writing systems have been identified in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, many from a single inscription. The limits of archaeological dating methods make it difficult to establish which was the earliest and hence the progenitor from which the others developed. The best documented and deciphered Mesoamerican writing system, and the most widely known, is the classic Maya script. Earlier scripts with poorer and varying levels of decipherment include the Olmec hieroglyphs, the Zapotec script, and the Isthmian script, all of which date back to the 1st millennium BC. An extensive Mesoamerican literature has been conserved, partly in indigenous scripts and partly in postconquest transcriptions in the Latin script.

The Zapotec civilization is an indigenous pre-Columbian civilization that flourished in the Valley of Oaxaca in Mesoamerica. Archaeological evidence shows that their culture originated at least 2,500 years ago. The Zapotec archaeological site at the ancient city of Monte Albán has monumental buildings, ball courts, tombs and grave goods, including finely worked gold jewelry. Monte Albán was one of the first major cities in Mesoamerica. It was the center of a Zapotec state that dominated much of the territory which today is known as the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

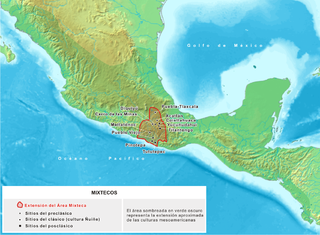

The Central Valleys of Oaxaca, also simply known as the Oaxaca Valley, is a geographic region located within the modern-day state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico. In an administrative context, it has been defined as comprising the districts of Etla, Centro, Zaachila, Zimatlán, Ocotlán, Tlacolula and Ejutla. The valley, which is located within the Sierra Madre Mountains, is shaped like a distorted and almost upside-down “Y,” with each of its arms bearing specific names: the northwestern Etla arm, the central southern Valle Grande, and the Tlacolula arm to the east. The Oaxaca Valley was home to the Zapotec civilization, one of the earliest complex societies in Mesoamerica, and the later Mixtec culture. A number of important and well-known archaeological sites are found in the Oaxaca Valley, including Monte Albán, Mitla, San José Mogote and Yagul. Today, the capital of the state, the city of Oaxaca, is located in the central portion of the valley.

The Zapotec script is the writing system of the Zapotec culture and represents one of the earliest writing systems in Mesoamerica. Rising in the late Pre-Classic era after the decline of the Olmec civilization, the Zapotecs of present-day Oaxaca built an empire around Monte Albán. One characteristic of Monte Albán is the large number of carved stone monuments one encounters throughout the plaza. There and at other sites, archaeologists have found extended text in a glyphic script.

Guiengola is a Zapotec archeological site located 14 km (8.7 mi) north of Tehuantepec, and 243 km (151 mi) southeast of Oaxaca city on Federal Highway 190. The visible ruins are located between a hill and a river, each carries the name of Guiengola. The name means "large stone" in the local variant of the Zapotec language. There are two main tombs that have been excavated, and both seem to be family interment sites. Both have front chambers that are for religious idols, while the rear chambers are for the burial of important people. The site also has fortified walls, houses, ballgame fields, other tombs and a very large "palace" with remains of artificial ponds and terraces. In the center of the site are 2 plazas, one lower than the other, and 2 pyramids, one to the east and one to the west.

Dainzú is a Zapotec archaeological site located in the eastern side of the Valles Centrales de Oaxaca, about 20 km south-east of the city of Oaxaca, Oaxaca State, Mexico. It is an ancient village near to and contemporary with Monte Albán and Mitla, with an earlier development. Dainzú was first occupied 700-600 BC but the main phase of occupation dates from about 200 BC to 350 AD. The site was excavated in 1965 by Mexican archaeologist Ignacio Bernal.

Chupícuaro is an important prehispanic archeological site from the late preclassical or formative period. The culture that takes its name from the site dates to 400 BC to 200 AD, or alternatively 500 BC to 300 AD., although some academics suggest an origin as early as 800 BC.

Huamelulpan is an archaeological site of the Mixtec culture, located in the town of San Martín Huamelulpan at an elevation of 2,218 metres (7,277 ft), about 96 kilometres (60 mi) north-west of the city of Oaxaca, the capital of Oaxaca state.

The use of mirrors in Mesoamerican culture was associated with the idea that they served as portals to a realm that could be seen but not interacted with. Mirrors in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica were fashioned from stone and served a number of uses, from the decorative to the divinatory. An ancient tradition among many Mesoamerican cultures was the practice of divination using the surface of a bowl of water as a mirror. At the time of the Spanish conquest this form of divination was still practiced among the Maya, Aztecs and Purépecha. In Mesoamerican art, mirrors are frequently associated with pools of liquid; this liquid was likely to have been water.

The first forms of economic organization in Pre-Hispanic Mexico were agriculture and hunting activities. The first people who inhabited the Mexican lands and part of Central America were great builders and later on creators of some of the most advanced civilizations of that time. The economy of that time, however, was based on the commercial activities, the division of society into classes, and later the importance that was generated in the economy by the so-called Tlatoani of the Aztecs.

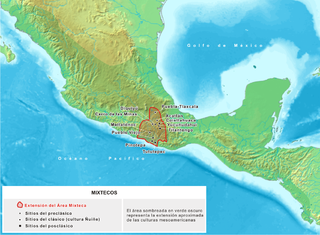

The Mixtec culture was a pre-hispanic archaeological culture, corresponding to the ancestors of the Mixtec people; they called themselves ñuu Savi, which means "people or nation of the rain". It had its first manifestations in the Mesoamerican Middle Preclassic period and ended with the Spanish conquest in the first decades of the 16th century. The historical territory of this people is the area known as La Mixteca, a mountainous region located between the current Mexican states of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

The Mesoamerican Classic Period is marked by the consolidation of the urban process that started in the Late Preclassic and later the Postclassic, which occurred until the third century A.D. During the first part of this era, Mesoameria was dominated by Teotihuacan. As of the fourth century A. D., this city started a major process of decay that allow the growth of the Maya, Zapotec, and central regional cultures of the Epiclassic.