Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), or fetal growth restriction, refers to poor growth of a fetus while in the womb during pregnancy. IUGR is defined by clinical features of malnutrition and evidence of reduced growth regardless of an infant's birth weight percentile. The causes of IUGR are broad and may involve maternal, fetal, or placental complications.

A maternal effect is a situation where the phenotype of an organism is determined not only by the environment it experiences and its genotype, but also by the environment and genotype of its mother. In genetics, maternal effects occur when an organism shows the phenotype expected from the genotype of the mother, irrespective of its own genotype, often due to the mother supplying messenger RNA or proteins to the egg. Maternal effects can also be caused by the maternal environment independent of genotype, sometimes controlling the size, sex, or behaviour of the offspring. These adaptive maternal effects lead to phenotypes of offspring that increase their fitness. Further, it introduces the concept of phenotypic plasticity, an important evolutionary concept. It has been proposed that maternal effects are important for the evolution of adaptive responses to environmental heterogeneity.

Gestational diabetes is a condition in which a woman without diabetes develops high blood sugar levels during pregnancy. Gestational diabetes generally results in few symptoms; however, it increases the risk of pre-eclampsia, depression, and of needing a Caesarean section. Babies born to mothers with poorly treated gestational diabetes are at increased risk of macrosomia, of having hypoglycemia after birth, and of jaundice. If untreated, diabetes can also result in stillbirth. Long term, children are at higher risk of being overweight and of developing type 2 diabetes.

Thrifty phenotype refers to the correlation between low birth weight of neonates and the increased risk of developing metabolic syndromes later in life, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Although early life undernutrition is thought to be the key driving factor to the hypothesis, other environmental factors have been explored for their role in susceptibility, such as physical inactivity. Genes may also play a role in susceptibility of these diseases, as they may make individuals predisposed to factors that lead to increased disease risk.

Birth weight is the body weight of a baby at its birth. The average birth weight in babies of European and African descent is 3.5 kilograms (7.7 lb), with the normative range between 2.5 and 4.0 kilograms. On average, babies of Asian descent weigh about 3.25 kilograms (7.2 lb). The prevalence of low birth weight has changed over time. Trends show a slight decrease from 7.9% (1970) to 6.8% (1980), then a slight increase to 8.3% (2006), to the current levels of 8.2% (2016). The prevalence of low birth weights has trended slightly upward from 2012 to the present.

For pregnant women with diabetes, some particular challenges exist for both mother and child. If the pregnant woman has diabetes as a pre-existing disorder, it can cause early labor, birth defects, and larger than average infants. Therefore, experts advise diabetics to maintain blood sugar level close to normal range about 3 months before planning for pregnancy.

Intrauterine hypoxia occurs when the fetus is deprived of an adequate supply of oxygen. It may be due to a variety of reasons such as prolapse or occlusion of the umbilical cord, placental infarction, maternal diabetes and maternal smoking. Intrauterine growth restriction may cause or be the result of hypoxia. Intrauterine hypoxia can cause cellular damage that occurs within the central nervous system. This results in an increased mortality rate, including an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Oxygen deprivation in the fetus and neonate have been implicated as either a primary or as a contributing risk factor in numerous neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders such as epilepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, eating disorders and cerebral palsy.

Human placental lactogen (hPL), also called human chorionic somatomammotropin (hCS) or human chorionic somatotropin, is a polypeptide placental hormone, the human form of placental lactogen. Its structure and function are similar to those of human growth hormone. It modifies the metabolic state of the mother during pregnancy to facilitate energy supply to the fetus. hPL has anti-insulin properties. hPL is a hormone secreted by the syncytiotrophoblast during pregnancy. Like human growth hormone, hPL is encoded by genes on chromosome 17q22-24. It was identified in 1963.

Maternal obesity refers to obesity of a woman during pregnancy. Parental obesity refers to obesity of either parent during pregnancy.

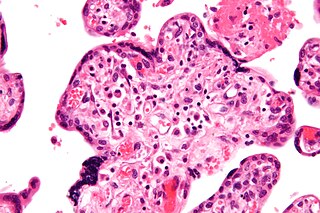

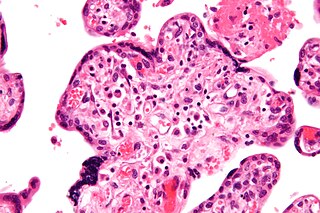

A placental disease is any disease, disorder, or pathology of the placenta.

Prenatal nutrition addresses nutrient recommendations before and during pregnancy. Nutrition and weight management before and during pregnancy has a profound effect on the development of infants. This is a rather critical time for healthy development since infants rely heavily on maternal stores and nutrient for optimal growth and health outcome later in life.

Nutriepigenomics is the study of food nutrients and their effects on human health through epigenetic modifications. There is now considerable evidence that nutritional imbalances during gestation and lactation are linked to non-communicable diseases, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer. If metabolic disturbances occur during critical time windows of development, the resulting epigenetic alterations can lead to permanent changes in tissue and organ structure or function and predispose individuals to disease.

Developmental Origins of Health and Disease is an approach to medical research factors that can lead to the development of human diseases during early life development. These factors include the role of prenatal and perinatal exposure to environmental factors, such as undernutrition, stress, environmental chemical, etc. This approach includes an emphasis on epigenetic causes of adult chronic non-communicable diseases. As well as physical human disease, the psychopathology of the foetus can also be predicted by epigenetic factors.

Obstetric medicine, similar to maternal medicine, is a sub-specialty of general internal medicine and obstetrics that specializes in process of prevention, diagnosing, and treating medical disorders in with pregnant women. It is closely related to the specialty of maternal-fetal medicine, although obstetric medicine does not directly care for the fetus. The practice of obstetric medicine, or previously known as "obstetric intervention," primarily consisted of the extraction of the baby during instances of duress, such as obstructed labor or if the baby was positioned in breech.

The fetal origins hypothesis proposes that the period of gestation has significant impacts on the developmental health and wellbeing outcomes for an individual ranging from infancy to adulthood. The effects of fetal origin are marked by three characteristics: latency, wherein effects may not be apparent until much later in life; persistency, whereby conditions resulting from a fetal effect continue to exist for a given individual; and genetic programming, which describes the 'switching on' of a specific gene due to prenatal environment. Research in the areas of economics, epidemiology, and epigenetics offer support for the hypothesis.

Maternal fetal stress transfer is a physiological phenomenon in which psychosocial stress experienced by a mother during her pregnancy can be transferred to the fetus. Psychosocial stress describes the brain's physiological response to perceived social threat. Because of a link in blood supply between a mother and fetus, it has been found that stress can leave lasting effects on a developing fetus, even before a child is born. According to recent studies, these effects are mainly the result of two particular stress biomarkers circulating in the maternal blood supply: cortisol and catecholamines.

Fetal programming, also known as prenatal programming, is the theory that environmental cues experienced during fetal development play a seminal role in determining health trajectories across the lifespan.

The first 1000 days describes the period from conception to 24 months of age in child development. This is considered a "critical period" in which sufficient nutrition and environmental factors have life-long effects on a child's overall health. While adequate nutrition can be exceptionally beneficial during this critical period, inadequate nutrition may also be detrimental to the child. This is because children establish many of their lifetime epigenetic characteristics in their first 1000 days. Medical and public health interventions early on in child development during the first 1000 days may have higher rates of success compared to those achieved outside of this period.

Diabetic embryopathy refers to congenital maldevelopments that are linked to maternal diabetes. Prenatal exposure to hyperglycemia can result in spontaneous abortions, perinatal mortality, and malformations. Type 1 and Type 2 diabetic pregnancies both increase the risk of diabetes induced teratogenicity. The rate of congenital malformations is similar in Type 1 and 2 mothers because of increased adiposity and the age of women with type 2 diabetes. Genetic predisposition and different environmental factors both play a significant role in the development of diabetic embryopathy. Metabolic dysfunction in pregnant mothers also increases the risk of fetal malformations.

Nutritional epigenetics is a science that studies the effects of nutrition on gene expression and chromatin accessibility. It is a subcategory of nutritional genomics that focuses on the effects of bioactive food components on epigenetic events.