Kohlrabi, also called German turnip or turnip cabbage, is a biennial vegetable, a low, stout cultivar of wild cabbage. It is a cultivar of the same species as cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, Savoy cabbage, and gai lan.

A macrobiotic diet is an unconventional restrictive diet based on ideas about types of food drawn from Zen Buddhism. The diet tries to balance the supposed yin and yang elements of food and cookware. Major principles of macrobiotic diets are to reduce animal products, eat locally grown foods that are in season, and consume meals in moderation.

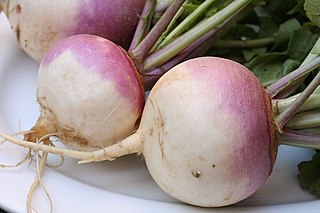

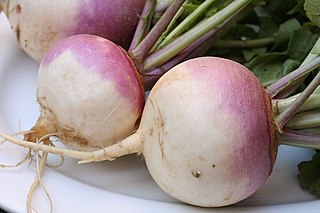

The turnip or white turnip is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. Small, tender varieties are grown for human consumption, while larger varieties are grown as feed for livestock. The name turnip – used in many regions – may also be used to refer to rutabaga, which is a different but related vegetable.

Cabbage, comprising several cultivars of Brassica oleracea, is a leafy green, red (purple), or white biennial plant grown as an annual vegetable crop for its dense-leaved heads. It is descended from the wild cabbage, and belongs to the "cole crops" or brassicas, meaning it is closely related to broccoli and cauliflower ; Brussels sprouts ; and Savoy cabbage.

Alfalfa, also called lucerne, is a perennial flowering plant in the legume family Fabaceae. It is cultivated as an important forage crop in many countries around the world. It is used for grazing, hay, and silage, as well as a green manure and cover crop. The name alfalfa is used in North America. The name lucerne is more commonly used in the United Kingdom, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. The plant superficially resembles clover, especially while young, when trifoliate leaves comprising round leaflets predominate. Later in maturity, leaflets are elongated. It has clusters of small purple flowers followed by fruits spiralled in two to three turns containing 10–20 seeds. Alfalfa is native to warmer temperate climates. It has been cultivated as livestock fodder since at least the era of the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Broccoli is an edible green plant in the cabbage family whose large flowering head, stalk and small associated leaves are eaten as a vegetable. Broccoli is classified in the Italica cultivar group of the species Brassica oleracea. Broccoli has large flower heads, or florets, usually dark green, arranged in a tree-like structure branching out from a thick stalk, which is usually light green. The mass of flower heads is surrounded by leaves. Broccoli resembles cauliflower, which is a different but closely related cultivar group of the same Brassica species.

The radish is a flowering plant in the mustard family, Brassicaceae. Its large taproot is commonly used as a root vegetable, although the entire plant is edible and its leaves are sometimes used as a leaf vegetable. Originally domesticated in Asia, radishes are now grown and consumed throughout the world. The radish is sometimes considered to form a species complex with the wild radish, and instead given the trinomial name Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus.

The lentil is an edible legume. It is an annual plant known for its lens-shaped seeds. It is about 40 cm (16 in) tall, and the seeds grow in pods, usually with two seeds in each.

Sprouting is the natural process by which seeds or spores germinate and put out shoots, and already established plants produce new leaves or buds, or other structures experience further growth.

The Brussels sprout is a member of the Gemmifera cultivar group of cabbages, grown for its edible buds.

Collard is a group of loose-leafed cultivars of Brassica oleracea, the same species as many common vegetables including cabbage and broccoli. Part of the Acephala (kale) cultivar group, it is also classified as the variety B. oleracea var. viridis.

Kale, also called leaf cabbage, belongs to a group of cabbage cultivars primarily grown for their edible leaves. It has also been used as an ornamental plant.

Broccolini, Aspabroc, baby broccoli or tenderstem broccoli, is a green vegetable similar to broccoli but with smaller florets and longer, thin stalks. It is a hybrid of broccoli and gai lan, both cultivar groups of Brassica oleracea. In the United States, the name Broccolini is a registered trademark of Mann Packing.

Wheatgrass is the freshly sprouted first leaves of the common wheat plant, used as a food, drink, or dietary supplement. Wheatgrass is served freeze dried or fresh, and so it differs from wheat malt, which is convectively dried. Wheatgrass is allowed to grow longer and taller than wheat malt.

An heirloom tomato is an open-pollinated, non-hybrid heirloom cultivar of tomato. They are classified as family heirlooms, commercial heirlooms, mystery heirlooms, or created heirlooms. They usually have a shorter shelf life and are less disease resistant than hybrids. They are grown for various reasons: for food, historical interest, access to wider varieties, and by people who wish to save seeds from year to year, as well as for their taste.

A seedling is a young sporophyte developing out of a plant embryo from a seed. Seedling development starts with germination of the seed. A typical young seedling consists of three main parts: the radicle, the hypocotyl, and the cotyledons. The two classes of flowering plants (angiosperms) are distinguished by their numbers of seed leaves: monocotyledons (monocots) have one blade-shaped cotyledon, whereas dicotyledons (dicots) possess two round cotyledons. Gymnosperms are more varied. For example, pine seedlings have up to eight cotyledons. The seedlings of some flowering plants have no cotyledons at all. These are said to be acotyledons.

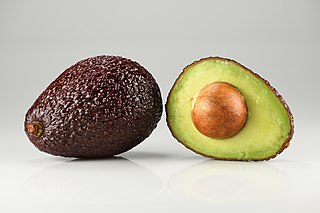

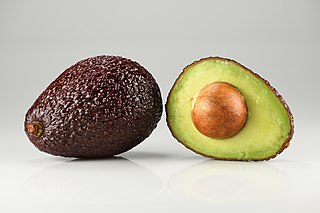

The Hass avocado is a variety of avocado with dark green, bumpy skin. It was first grown and sold by Southern California mail carrier and amateur horticulturist Rudolph Hass, who also gave it his name.

Vegetables are parts of plants that are consumed by humans or other animals as food. The original meaning is still commonly used and is applied to plants collectively to refer to all edible plant matter, including the flowers, fruits, stems, leaves, roots, and seeds. An alternative definition of the term is applied somewhat arbitrarily, often by culinary and cultural tradition. It may exclude foods derived from some plants that are fruits, flowers, nuts, and cereal grains, but include savoury fruits such as tomatoes and courgettes, flowers such as broccoli, and seeds such as pulses.

Broccoli sprouts are three- to four-day-old broccoli plants that look like alfalfa sprouts, but taste like radishes.

The Future 50 Foods report, subtitled "50 foods for healthier people and a healthier planet", was published in February 2019 by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and Knorr. It identifies 50 plant-based foods that can increase dietary nutritional value and reduce environmental impacts of the food supply, promoting sustainable global food systems.