Related Research Articles

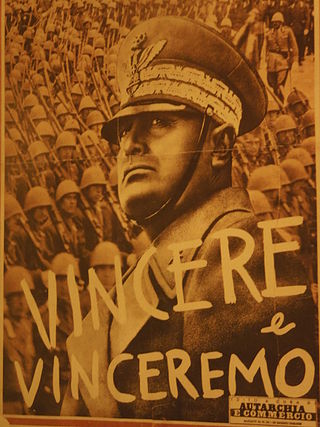

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultranationalist political ideology and movement, characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hierarchy, subordination of individual interests for the perceived good of the nation or race, and strong regimentation of society and the economy.

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, following the start of the Second World War, the party was proscribed by the British government and in 1940 it was disbanded.

The National Front (NF) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is currently led by Tony Martin. A minor party, it has never had its representatives elected to the British or European Parliaments, although it gained a small number of local councillors through defections and it has had a few of its representatives elected to community councils. Founded in 1967, it reached the height of its electoral support during the mid-1970s, when it was briefly England's fourth-largest party in terms of vote share.

The history of fascist ideology is long and it draws on many sources. Fascists took inspiration from sources as ancient as the Spartans for their focus on racial purity and their emphasis on rule by an elite minority. Fascism has also been connected to the ideals of Plato, though there are key differences between the two. Fascism styled itself as the ideological successor to Rome, particularly the Roman Empire. From the same era, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's view on the absolute authority of the state also strongly influenced fascist thinking. The French Revolution was a major influence insofar as the Nazis saw themselves as fighting back against many of the ideas which it brought to prominence, especially liberalism, liberal democracy and racial equality, whereas on the other hand, fascism drew heavily on the revolutionary ideal of nationalism. The prejudice of a "high and noble" Aryan culture as opposed to a "parasitic" Semitic culture was core to Nazi racial views, while other early forms of fascism concerned themselves with non-racialized conceptions of the nation.

What constitutes a definition of fascism and fascist governments has been a complicated and highly disputed subject concerning the exact nature of fascism and its core tenets debated amongst historians, political scientists, and other scholars ever since Benito Mussolini first used the term in 1915. Historian Ian Kershaw once wrote that "trying to define 'fascism' is like trying to nail jelly to the wall".

The Common Man's Front, also translated as Front of the Ordinary Man, was a short-lived right-wing populist, monarchist and anti-communist political party in Italy. It was formed shortly after the end of the Second World War and participated in the first post-war election for the constituent assembly in 1946. Its leader was the Roman writer Guglielmo Giannini, and its symbol was the banner of Giannini's newspaper L'Uomo qualunque.

Fascist movements in Europe were the set of various fascist ideologies which were practiced by governments and political organizations in Europe during the 20th century. Fascism was born in Italy following World War I, and other fascist movements, influenced by Italian Fascism, subsequently emerged across Europe. Among the political doctrines which are identified as ideological origins of fascism in Europe are the combining of a traditional national unity and revolutionary anti-democratic rhetoric which was espoused by the integral nationalist Charles Maurras and the revolutionary syndicalist Georges Sorel.

The Croix-de-Feu was a nationalist French league of the Interwar period, led by Colonel François de la Rocque (1885–1946). After it was dissolved, as were all other leagues during the Popular Front period (1936–38), La Rocque established the Parti social français (PSF) to replace it.

Fascist movements gained popularity in many countries in Asia during the 1920s.

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Robert Pretyman Newman was an Irish-born British Army officer and Conservative politician.

Corporatism is a political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, come together on and negotiate contracts or policy on the basis of their common interests. The term is derived from the Latin corpus, or "body".

The Anti-Socialist Union was a British political pressure group that supported free trade economics and opposed socialism. The group was active from 1908 to 1949, with its heyday occurring before the First World War.

Lieutenant-Colonel Graham Seton Hutchison was a British First World War army officer, military theorist, author of both adventure novels and non-fiction works and fascist activist. Seton Hutchison became a celebrated figure in military circles for his tactical innovations during the First World War but would later become associated with a series of fringe fascist movements which failed to capture much support even by the standards of the far right in Britain in the interbellum period. He made a contribution to First World War fiction with his espionage novel, The W Plan.

British fascism is the form of fascism which is promoted by some political parties and movements in the United Kingdom. It is based on British ultranationalism and imperialism and had aspects of Italian fascism and Nazism both before and after World War II.

George Ranken Askwith, 1st Baron Askwith, KCB, KC, known as Sir George Askwith between 1911 and 1919, was an English lawyer, civil servant and industrial arbitrator.

National syndicalism is a far-right adaptation of syndicalism to suit the broader agenda of integral nationalism. National syndicalism developed in France in the early 20th century, and then spread to Italy, Spain, and Portugal.

The British Fascists was the first political organisation in the United Kingdom to claim the label of fascism, formed in 1923. The group had little ideological unity apart from anti-socialism for much of its existence, and was strongly associated with British conservatism. William Joyce, Neil Francis Hawkins, Maxwell Knight and Arnold Leese were amongst those to have passed through the movement as members and activists.

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were opposed by many countries forming the Allies of World War II and dozens of resistance movements worldwide. Anti-fascism has been an element of movements across the political spectrum and holding many different political positions such as anarchism, communism, pacifism, republicanism, social democracy, socialism and syndicalism as well as centrist, conservative, liberal and nationalist viewpoints.

The Militant Christian Patriots (MCP) were a short-lived but influential anti-Semitic organisation active in the United Kingdom immediately prior to the Second World War. It played a central role in the ultimately unsuccessful attempts to keep the UK out of any European war.

References

- ↑ The Globe, 27 February 1919, p.6

- ↑ Maurice Cowling, The Impact of Labour. 1920-1924 (Cambridge University Press, 1971), p. 65.

- ↑ Walter Garrison Runciman, Applied social theory, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 144.

- ↑ Greta Jones, Social Hygiene in twentieth century Britain, Taylor & Francis, 1986, p. 21.

- ↑ E. H. H. Green, Ideologies of Conservatism: conservative political ideas in the twentieth century, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 122-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas P. Linehan, British Fascism, 1918-39: parties, ideology and culture, Manchester University Press, 2000, p. 45.