The Minute Women of the U.S.A. was one of the largest of a number of anti-Communist women's groups that were active during the 1950s and early 1960s. Such groups, which organized American suburban housewives into anti-Communist study groups, political activism and letter-writing campaigns, were a bedrock of support for McCarthyism.

The primary concerns of the Minute Women and other similar groups were the exposure of Communist subversion, the defense of constitutional limits, opposition to Atheism, Socialism and social welfare provisions such as the New Deal; and rejection of Internationalism, particularly in the form of the United Nations. They campaigned to expose supposedly Communist individuals, focusing particularly on school and university administrators.

The Minute Women were a national group founded by Suzanne Stevenson of Connecticut in September 1949. They grew rapidly, especially in Texas, California, West Virginia, Maryland, and Connecticut. By 1952 they had over 50,000 members. They were predominantly white middle and upper-class women aged between thirty and sixty, with school-aged or grown children. Chapters were relatively small, numbering only a few dozen to a few hundred people. The Houston chapter, which later became famous, was one of the largest in the nation with around 500 members. Over sixty of the Houstonian Minute Women were doctors' wives, reflecting medical opposition to socialized medicine.

Unlike many other anti-Communist groups, the Minute Women operated in a semi-covert fashion. Stevenson instructed members to never reveal that they were Minute Women and always present themselves as individual concerned citizens. In her view, political activism was more effective when it appeared to be spontaneous. [1]

The organization was structured in a unique fashion, ostensibly to defend against Communist infiltration. It had no constitution or bylaws, no parliamentary procedure to guide the meetings, and no option for motions from the floor; its officers were appointed rather than elected. Its members communicated via a chain-telephoning system in which one member called five others, who in turn made five more calls, enabling hundreds to be contacted within a short space of time. [2] Membership of the Minute Women was restricted to American citizens, though the group's founder had been born in Belgium and was the sister of the Belgian Ambassador, Baron Robert Silvercruys. [3] The Minute Women sought to apply political pressure through letter-writing campaigns, heckling speakers and swamping their opponents with telephone calls. In Houston, Texas, where they were particularly strong, they took over the local school board and claimed to have planted observers in University of Houston classrooms to watch out for controversial material and teachers. [3] [4]

Their tactics were highly effective; as the Houston Post noted, "Many public officials… who might… defy a lone organization… would be loath to go against the wishes of 500 individuals." The Houston Minute Women harassed and instigated the firing of teachers and school administrators, including the deputy superintendent of the Houston public schools, for alleged Communism. They also forced the university to eliminate history programs from its educational television broadcasts. An annual essay-writing contest sponsored by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was banned on the grounds that UNESCO was unacceptably "internationalist". At one point, the Minute Women circulated a report that "troops flying the United Nations flag once took over several American cities in a surprise move, throwing the mayors in jail and locking up the police chiefs." A member who pointed out the falsity of the report found herself ruled out of order by her fellow Minute Women. [3]

Even well-respected groups and individuals found themselves targeted by the Minute Women. The Quakers' American Friends Service Committee was refused permission to use a Houston meeting hall after the Minute Women protested that Alger Hiss had once attended a Quaker meeting. Rufus Clement, the president of Atlanta University and the first-ever African-American to serve on the Atlanta Board of Education, faced protests from Minute Women when he lectured at a Houston Methodist church, on the grounds that he was "too controversial". The Houston Post commented that "a new meaning has been given to the word controversial… It now often becomes a derogatory epithet, frequently synonymous with the word Communist." [3] There was an overt element of racism in the Minute Women's activities, which included distributing anti-semitic literature and opposing proponents of integrated schools, which they regarded as Communist-inspired advocates of "race mongrelization." [5]

The Minute Women's campaign in Houston was eventually blunted by an exposé by the Houston Post in 1953, which published an eleven-part series of articles by reporter Ralph O'Leary which highlighted the group's activities. The newspaper was deluged by an avalanche of mail which was largely complimentary of the newspaper's courage in taking on the Minute Women. O'Leary's reports were widely praised, with Time magazine describing the Post's coverage as "a model of how a newspaper can effectively expose irresponsible vigilantism." [3]

Despite this setback the Minute Women remained active throughout the remainder of the 1950s and into the 1960s. They played a major role in stoking the 1956 controversy over the Alaska Mental Health Bill (HR 6376), claiming that the bill was an attempt by Congress to give the government authority to abduct citizens at will and imprison them in concentration camps in Alaska. [1] The group finally faded away as the nation turned against McCarthyism and the anti-Communist hysteria diminished.

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in which it appears. In Western culture, depending on the particular nation, conservatives seek to promote a range of institutions, such as the nuclear family, organized religion, the military, the nation-state, property rights, rule of law, aristocracy, and monarchy. Conservatives tend to favour institutions and practices that guarantee social order and historical continuity.

The 1952 United States presidential election was the 42nd quadrennial presidential election and was held on Tuesday, November 4, 1952. Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower won a landslide victory over Illinois Democratic Governor Adlai Stevenson II, becoming the first Republican president in 20 years. This was the first election since 1928 without an incumbent president on the ballot. Eisenhower was re-elected in 1956 in a rematch with Stevenson.

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property or tradition. Hierarchy and inequality may be seen as natural results of traditional social differences or competition in market economies.

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some theories of political movements are the political opportunity theory, which states that political movements stem from mere circumstances, and the resource mobilization theory which states that political movements result from strategic organization and relevant resources. Political movements are also related to political parties in the sense that they both aim to make an impact on the government and that several political parties have emerged from initial political movements. While political parties are engaged with a multitude of issues, political movements tend to focus on only one major issue.

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional power structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social institutions, such as traditional family structures, gender roles, sexual relations, national patriotism, and religious traditions. Social conservatism is usually skeptical of social change, instead tending to support the status quo concerning social issues.

The John Birch Society (JBS) is an American right-wing political advocacy group. Founded in 1958, it is anti-communist, supports social conservatism, and is associated with ultraconservative, radical right, far-right, right-wing populist, and right-wing libertarian ideas. Originally based in Belmont, Massachusetts, the JBS is now headquartered in Grand Chute, Wisconsin, with local chapters throughout the United States. It owns American Opinion Publishing, Inc., which publishes the magazine The New American, and it is affiliated with an online school called FreedomProject Academy.

Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) is a conservative youth activism organization that was founded in 1960 as a coalition between traditional conservatives and libertarians on American college campuses. It is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and the chapter affiliate of Young America's Foundation. The purposes of YAF are to advocate public policies consistent with the Sharon Statement, which was adopted by young conservatives at a meeting at the home of William F. Buckley in Sharon, Connecticut, on September 11, 1960.

Robert Henry Winborne Welch Jr. was an American businessman, political organizer, and conspiracy theorist. He was wealthy following his retirement from the candy business and used his wealth to sponsor anti-communist causes. He co-founded the John Birch Society (JBS), an American right-wing political advocacy group, in 1958 and tightly controlled it until his death. He was highly controversial and criticized by liberals, as well as some conservatives, including William F. Buckley Jr. only after being an early donor to Buckley’s National Review in the 1950s.

Eagle Forum is a conservative interest group in the United States founded by Phyllis Schlafly in 1972 and is the parent organization that also includes the Eagle Forum Education and Legal Defense Fund and the Eagle Forum PAC. The Eagle Forum has been primarily focused on social issues; it describes itself as pro-family and reports membership of 80,000. Critics have described it as socially conservative and anti-feminist.

The American Public Relations Forum (APRF) was a conservative anti-communist organization for Catholic women, established in southern California in 1952 with its headquarters in Burbank. It was founded by Stephanie Williams, a San Fernando Valley housewife, who told the opening meeting of the group that "we are wives and mothers who are vitally interested in what is happening in our country." It campaigned against anything it saw as socialist or anti-nationalist, organizing meetings and letter-writing campaigns to apply political pressure as well as issuing monthly newsletters and "emergency bulletins" on issues of urgent concern.

The Alaska Mental Health Enabling Act of 1956 was an Act of Congress passed to improve mental health care in the United States territory of Alaska. It became the focus of a major political controversy after opponents nicknamed it the "Siberia Bill" and denounced it as being part of a communist plot to hospitalize and brainwash Americans. Campaigners asserted that it was part of an international Jewish, Roman Catholic or psychiatric conspiracy intended to establish United Nations-run concentration camps in the United States.

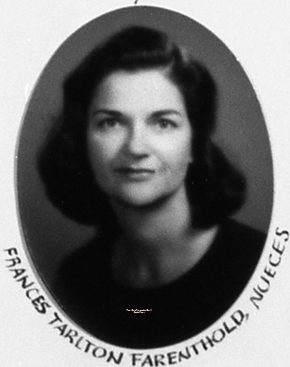

Mary Frances Tarlton "Sissy" Farenthold was an American politician, attorney, activist, and educator. She was best known for her two campaigns for governor of Texas in 1972 and 1974, and for being placed in nomination for vice president of the United States, finishing second at the 1972 Democratic National Convention. She was elected as the first chair of the National Women's Political Caucus in 1973.

In the politics of the United States, the radical right is a political preference that leans towards ultraconservatism, white nationalism, white supremacy, or other far-right ideologies in a hierarchical structure which is paired with conspiratorial rhetoric alongside traditionalist and reactionary aspirations. The term was first used by social scientists in the 1950s regarding small groups such as the John Birch Society in the United States, and since then it has been applied to similar groups worldwide. The term "radical" was applied to the groups because they sought to make fundamental changes within institutions and remove persons and institutions that threatened their values or economic interests from political life.

Social conservatism in the United States is a political ideology focused on the preservation of traditional values and beliefs. It focuses on a concern with moral and social values which proponents of the ideology see as degraded in modern society by liberalism. In the United States, one of the largest forces of social conservatism is the Christian right.

Conservatism in South Korea is a political and social philosophy characterized by Korean culture and from Confucianism. South Korean conservative parties largely believe in stances such as a developmental state, pro-business, opposition to trade unions, strong national defense, anti-communism, pro-communitarianism, pro-United States and pro-European in foreign relations, pay attention on North Korean defectors, sanctions and human rights, and recently free trade, economic liberalism, and neoliberalism.

Women in conservatism in the United States have advocated for social, political, economic, and cultural conservative policies since anti-suffragism. Leading conservative women such as Phyllis Schlafly have expressed that women should embrace their privileged essential nature. This thread of belief can be traced through the anti-suffrage movement, the Red Scare, and the Reagan Era, and is still present in the 21st century, especially in several conservative women's organizations such as Concerned Women for America and the Independent Women's Forum.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to politics and political science:

An anti-war movement is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term anti-war can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conflicts, or to anti-war books, paintings, and other works of art. Some activists distinguish between anti-war movements and peace movements. Anti-war activists work through protest and other grassroots means to attempt to pressure a government to put an end to a particular war or conflict or to prevent it in advance.

There has never been a national political party in the United States called the Conservative Party. All major American political parties support republicanism and the basic classical liberal ideals on which the country was founded in 1776, emphasizing liberty, the pursuit of happiness, the rule of law, the consent of the governed, opposition to aristocracy and fear of corruption, coupled with equal rights before the law. Political divisions inside the United States often seemed minor or trivial to Europeans, where the divide between the Left and the Right led to violent political polarization, starting with the French Revolution.

Proposition 1 was a referendum held on November 3, 2015, on the anti-discrimination ordinance known as the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance (HERO). The ordinance was intended to improve anti-discrimination coverage based on sexual orientation and gender identity in Houston, specifically in areas such as housing and occupation where no anti-discrimination policy existed. Proposition 1 asked voters whether they approved HERO. Houston voters rejected Proposal 1 by a vote of 61% to 39%.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)