Related Research Articles

Muhammad V an-Nasir, commonly known Naceur Bey was the son of Muhammad II ibn al-Husayn and the fifteenth Husainid Bey of Tunis, ruling from 1906 until his death. He was named Divisional General of the Beylical army when he became Bey al-Mahalla on 11 June 1902, and assumed the rank of Marshal when he succeeded Muhammad IV al-Hadi on 11 May 1906.

Tunisian Arabic, or simply Tunisian, is a set of dialects of Maghrebi Arabic spoken in Tunisia. It is known among its over 11 million speakers as Tounsi [ˈtunsi](listen), "Tunisian" or Derja "Everyday Language" to distinguish it from Modern Standard Arabic, the official language of Tunisia. Tunisian Arabic is mostly similar to eastern Algerian Arabic and western Libyan Arabic.

The Young Tunisians was a Tunisian political party and political reform movement in the early 20th century. Its main goal was to advocate for reforms in the French protectorate in order to give more political autonomy and equal treatment to Tunisians.

Tunisian independence was a process that occurred from 1952 to 1956 between France and a separatist movement, led by Habib Bourguiba. He became the first Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Tunisia after negotiations with France successfully had brought an end to the colonial protectorate and led to independence.

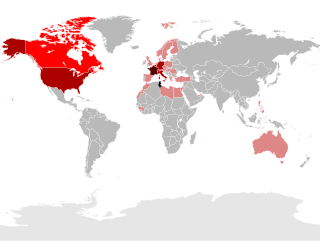

Tunisians are the citizens and nationals of Tunisia in North Africa, who speak Tunisian Arabic and share a common Tunisian culture and identity. In addition, a Tunisian diaspora has been established with modern migration, particularly in Western Europe, namely France, Italy and Germany.

The Beylik of Tunis, also known as Kingdom of Tunis was a largely autonomous beylik of the Ottoman Empire located in present-day Tunisia. It was ruled by the Husainid dynasty from 1705 until the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the French protectorate of Tunisia in 1881.

Ahmed I, born 2 December 1805 in Tunis died 30 May 1855 at La Goulette, was the tenth Husainid Bey of Tunis, ruling from 1837 until his death. He was responsible for the abolition of slavery in Tunisia in 1846.

The history of Tunisia under French rule started in 1881 with the establishment of the French protectorate and ended in 1956 with Tunisian independence. The French presence in Tunisia came five decades after their occupation of neighboring Algeria. Both of these lands had been associated with the Ottoman Empire for three centuries, yet each had long since attained political autonomy. Before the French arrived, the Bey of Tunisia had begun a process of modern reforms, but financial difficulties mounted, resulting in debt. A commission of European creditors then took over the finances. After the French conquest of Tunisia the French government assumed Tunisia's international obligations. Major developments and improvements were undertaken by the French in several areas, including transport and infrastructure, industry, the financial system, public health, administration, and education. Although these developments were welcome, nonetheless French businesses and citizens were clearly being favored over Tunisians. Their ancient national sense was early expressed in speech and in print; political organization followed. The independence movement was already active before World War I, and continued to gain strength against mixed French opposition. Its ultimate aim was achieved in 1956.

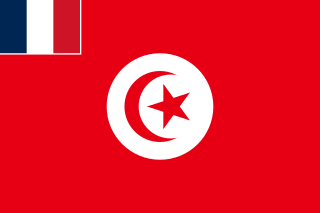

The French protectorate of Tunisia, commonly referred to as simply French Tunisia, was established in 1881, during the French colonial Empire era, and lasted until Tunisian independence in 1956.

The Tunisian national movement was a sociopolitical movement, born at the beginning of the 20th century, which led to the fight against the French protectorate of Tunisia and gained Tunisian independence in 1956. Inspired by the ideology of the Young Turks and Tunisian political reforms in the latter half of the 19th century, the group of traditionalists—lawyers, doctors and journalists—gradually gave way to a well-structured political organisation of the new French-educated elite. The organisation could mobilise supporters to confront the authorities of the protectorate in order to advance the demands that it made of the French government. The movement's strategy alternated between negotiations and armed confrontations over the years. Support from the powerful trade unions and the feminist movement, along with an intellectual and musical cultural revival, contributed to a strong assertion of national identity which was reinforced by the educational and political systems after independence.

The Turks in Tunisia, also known as Turco-Tunisians and Tunisian Turks, are ethnic Turks who constitute one of the minority groups in Tunisia.

Ali Bach Hamba was a Tunisian lawyer, journalist and politician. He co-founded the Young Tunisians with Béchir Sfar in 1907.

The Tunis tram boycott was a mass protest which began in Tunis on 9 February 1912. For more than a month, Tunisian Arabs refused to ride on the city trams until a series of demands were met. The boycott, though unsuccessful, is considered an important step in the development of the Tunisian nationalist movement.

Sofiane Bouhdiba is a Tunisian demographer, born on 12 April 1968. He is Professor of Demography in the department of Sociology in the University of Tunis. He has taught in many universities in Europe, Africa and the United States, and has participated in a great number of international conferences, with a focus on mortality and morbidity. As an international consultant to the United Nations, he had the opportunity to observe closely the history of the fight against major diseases in the world. He has also participated in numerous scientific and humanitarian missions in sub-Saharan Africa. Professor Sofiane Bouhdiba is well-known for the realism of his recommendations, and has been appointed as an expert in Demography before the Tunisian Parliament.

Abdeljelil Zaouche was a Tunisian politician, reformer, and campaigner in the Tunisian independence movement.

The Tunisian Consultative Conference was an organ of government set up under the French Protectorate of Tunisia. Presided over by the French Resident-General or his representative, its remit was originally very narrow: it was not allowed to discuss political or constitutional matters, or public finances and accounts. At the same time it was accountable for “obligatory” spending, which included the civil list of the Bey and subsidies paid to the ruling Husainid dynasty, as well as the servicing of Tunisia's public debt and the management costs of French services in the protectorate. The steady evolution of this institution over time was a measure of the development of nationalist ideas. A generation of Tunisian politicians, including Abdeljelil Zaouche, Tahar Ben Ammar and Mohamed Chenik, made their entry into public life through the conference, and eventually negotiated the terms of Tunisian independence.

Béchir Sfar, , was a Tunisian nationalist campaigner and politician.

Lucette Valensi is a French historian néeLucette Chemla in Tunis.

Juliette Bessis was born in 1925 in Gabès, Tunisia, and died 2017 in Paris, France. She was a contemporary Tunisian scholar and historian specializing in the Maghreb region of northern Africa.

In Tunisia, makhzen was the term used to designate the political and administrative establishment of the Beylik of Tunis before the proclamation of the republic in 1957. The makhzen consisted of families of Turkish origin, or Turkish-speaking mamluks of European origin, intermarried with indigenous Tunisian families who were great merchants or landowners. This network of families dominated the high offices of state, the leadership of the army and the positions of rank and power in the regions outside the capital. They were also closely connected with the senior ulema. These were known as “makhzen families”. Outside of the capital and the major towns, the term 'makhzen' designated not the leading families close to the regime, but those of the interior tribes which had a trusted relationship with the ruling family. Together the great families and the loyal tribes made up the country's 'establishment'.

References

- 1 2 3 Derrick 2008 , 50.

- ↑ Ling 1979 , 92.

- ↑ Derrick 2008 , 52.