Related Research Articles

Boron nitride is a thermally and chemically resistant refractory compound of boron and nitrogen with the chemical formula BN. It exists in various crystalline forms that are isoelectronic to a similarly structured carbon lattice. The hexagonal form corresponding to graphite is the most stable and soft among BN polymorphs, and is therefore used as a lubricant and an additive to cosmetic products. The cubic variety analogous to diamond is called c-BN; it is softer than diamond, but its thermal and chemical stability is superior. The rare wurtzite BN modification is similar to lonsdaleite but slightly softer than the cubic form.

Ion implantation is a low-temperature process by which ions of one element are accelerated into a solid target, thereby changing the physical, chemical, or electrical properties of the target. Ion implantation is used in semiconductor device fabrication and in metal finishing, as well as in materials science research. The ions can alter the elemental composition of the target if they stop and remain in the target. Ion implantation also causes chemical and physical changes when the ions impinge on the target at high energy. The crystal structure of the target can be damaged or even destroyed by the energetic collision cascades, and ions of sufficiently high energy can cause nuclear transmutation.

Semiconductor device fabrication is the process used to manufacture semiconductor devices, typically integrated circuits (ICs) such as computer processors, microcontrollers, and memory chips. It is a multiple-step photolithographic and physico-chemical process during which electronic circuits are gradually created on a wafer, typically made of pure single-crystal semiconducting material. Silicon is almost always used, but various compound semiconductors are used for specialized applications.

A semiconductor is a material that is between the conductor and insulator in ability to conduct electical current. In many cases their conducting properties may be altered in useful ways by introducing impurities ("doping") into the crystal structure. When two differently doped regions exist in the same crystal, a semiconductor junction is created. The behavior of charge carriers, which include electrons, ions, and electron holes, at these junctions is the basis of diodes, transistors, and most modern electronics. Some examples of semiconductors are silicon, germanium, gallium arsenide, and elements near the so-called "metalloid staircase" on the periodic table. After silicon, gallium arsenide is the second-most common semiconductor and is used in laser diodes, solar cells, microwave-frequency integrated circuits, and others. Silicon is a critical element for fabricating most electronic circuits.

Epitaxy refers to a type of crystal growth or material deposition in which new crystalline layers are formed with one or more well-defined orientations with respect to the crystalline seed layer. The deposited crystalline film is called an epitaxial film or epitaxial layer. The relative orientation(s) of the epitaxial layer to the seed layer is defined in terms of the orientation of the crystal lattice of each material. For most epitaxial growths, the new layer is usually crystalline and each crystallographic domain of the overlayer must have a well-defined orientation relative to the substrate crystal structure. Epitaxy can involve single-crystal structures, although grain-to-grain epitaxy has been observed in granular films. For most technological applications, single-domain epitaxy, which is the growth of an overlayer crystal with one well-defined orientation with respect to the substrate crystal, is preferred. Epitaxy can also play an important role while growing superlattice structures.

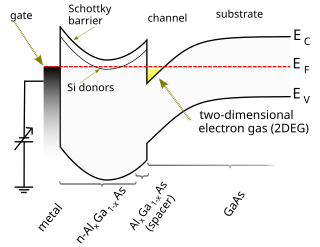

A high-electron-mobility transistor, also known as heterostructure FET (HFET) or modulation-doped FET (MODFET), is a field-effect transistor incorporating a junction between two materials with different band gaps as the channel instead of a doped region. A commonly used material combination is GaAs with AlGaAs, though there is wide variation, dependent on the application of the device. Devices incorporating more indium generally show better high-frequency performance, while in recent years, gallium nitride HEMTs have attracted attention due to their high-power performance.

In semiconductor production, doping is the intentional introduction of impurities into an intrinsic (undoped) semiconductor for the purpose of modulating its electrical, optical and structural properties. The doped material is referred to as an extrinsic semiconductor.

The threshold voltage, commonly abbreviated as Vth or VGS(th), of a field-effect transistor (FET) is the minimum gate-to-source voltage (VGS) that is needed to create a conducting path between the source and drain terminals. It is an important scaling factor to maintain power efficiency.

Rapid thermal processing (RTP) is a semiconductor manufacturing process which heats silicon wafers to temperatures exceeding 1,000°C for not more than a few seconds. During cooling wafer temperatures must be brought down slowly to prevent dislocations and wafer breakage due to thermal shock. Such rapid heating rates are often attained by high intensity lamps or lasers. These processes are used for a wide variety of applications in semiconductor manufacturing including dopant activation, thermal oxidation, metal reflow and chemical vapor deposition.

An ohmic contact is a non-rectifying electrical junction: a junction between two conductors that has a linear current–voltage (I–V) curve as with Ohm's law. Low-resistance ohmic contacts are used to allow charge to flow easily in both directions between the two conductors, without blocking due to rectification or excess power dissipation due to voltage thresholds.

In semiconductor electronics fabrication technology, a self-aligned gate is a transistor manufacturing approach whereby the gate electrode of a MOSFET is used as a mask for the doping of the source and drain regions. This technique ensures that the gate is naturally and precisely aligned to the edges of the source and drain.

An extrinsic semiconductor is one that has been doped; during manufacture of the semiconductor crystal a trace element or chemical called a doping agent has been incorporated chemically into the crystal, for the purpose of giving it different electrical properties than the pure semiconductor crystal, which is called an intrinsic semiconductor. In an extrinsic semiconductor it is these foreign dopant atoms in the crystal lattice that mainly provide the charge carriers which carry electric current through the crystal. The doping agents used are of two types, resulting in two types of extrinsic semiconductor. An electron donor dopant is an atom which, when incorporated in the crystal, releases a mobile conduction electron into the crystal lattice. An extrinsic semiconductor that has been doped with electron donor atoms is called an n-type semiconductor, because the majority of charge carriers in the crystal are negative electrons. An electron acceptor dopant is an atom which accepts an electron from the lattice, creating a vacancy where an electron should be called a hole which can move through the crystal like a positively charged particle. An extrinsic semiconductor which has been doped with electron acceptor atoms is called a p-type semiconductor, because the majority of charge carriers in the crystal are positive holes.

A metal gate, in the context of a lateral metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) stack, is the gate electrode separated by an oxide from the transistor's channel – the gate material is made from a metal. In most MOS transistors since about the mid-1970s, the "M" for metal has been replaced by polysilicon, but the name remained.

Local oxidation nanolithography (LON) is a tip-based nanofabrication method. It is based on the spatial confinement on an oxidation reaction under the sharp tip of an atomic force microscope.

A dopant is a small amount of a substance added to a material to alter its physical properties, such as electrical or optical properties. The amount of dopant is typically very low compared to the material being doped.

Ultra-high-temperature ceramics (UHTCs) are a type of refractory ceramics that can withstand extremely high temperatures without degrading, often above 2,000 °C. They also often have high thermal conductivities and are highly resistant to thermal shock, meaning they can withstand sudden and extreme changes in temperature without cracking or breaking. Chemically, they are usually borides, carbides, nitrides, and oxides of early transition metals.

Boron nitride nanosheet is a crystalline form of the hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), which has a thickness of one atom. Similar in geometry as well as physical and thermal properties to its carbon analog graphene, but has very different chemical and electronic properties – contrary to the black and highly conducting graphene, BN nanosheets are electrical insulators with a band gap of ~5.9 eV, and therefore appear white in color.

Two dimensional hexagonal boron nitride is a material of comparable structure to graphene with potential applications in e.g. photonics., fuel cells and as a substrate for two-dimensional heterostructures. 2D h-BN is isostructural to graphene, but where graphene is conductive, 2D h-BN is a wide-gap insulator.

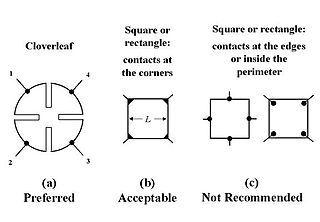

Differential Hall Effect Metrology (DHEM) is an electrical depth profiling technique that measures all critical electrical parameters through an electrically active material at sub-nanometer depth resolution. DHEM is based on the previously developed Differential Hall Effect (DHE) method. In the traditional DHE method, successive sheet resistance and Hall effect measurements on a semiconductor layer are made using Van der Pauw and Hall effect techniques. The thickness of the layer is reduced through successive processing steps in between measurements. This typically involves thermal, chemical or electrochemical etching or oxidation to remove material from the measurement circuit. This data can be used to determine the depth profiles of carrier concentration, resistivity and mobility. DHE is a manual laboratory technique requiring wet chemical processing for etching and cleaning the sample between each measurement, and it has not been widely used in the semiconductor industry. Since the contact region is also affected by the material removal process, the traditional DHE approach requires that contacts be newly and repeatedly be made to collect data on the coupon. This introduces contact related noise and reduces the repeatability and stability of the data. The speed, accuracy and, depth resolution of DHE has been generally limited because of its manual nature. The DHEM technique is an improvement over the traditional DHE method in terms of automation, speed, data stability and, resolution. DHEM technique had been deployed in a semi-automated or automated tools.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ho, Johnny C.; Yerushalmi, Roie; Jacobson, Zachery A.; Fan, Zhiyong; Alley, Robert L.; Javey, Ali (2007-11-11). "Controlled nanoscale doping of semiconductors via molecular monolayers". Nature Materials. 7 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 62–67. doi:10.1038/nmat2058. ISSN 1476-1122. PMID 17994026.

- 1 2 3 4 Ho, Johnny C.; Yerushalmi, Roie; Smith, Gregory; Majhi, Prashant; Bennett, Joseph; Halim, Jeffri; Faifer, Vladimir N.; Javey, Ali (2009-02-11). "Wafer-Scale, Sub-5 nm Junction Formation by Monolayer Doping and Conventional Spike Annealing". Nano Letters. 9 (2). American Chemical Society (ACS): 725–730. arXiv: 0901.1396 . doi:10.1021/nl8032526. ISSN 1530-6984. PMID 19161334. S2CID 13399984.

- ↑ Schmitz, J.; van Gestel, M.; Stolk, P.A.; Ponomarev, Y.V.; Roozeboom, F.; et al. Ultra-shallow junction formation by outdiffusion from implanted oxide. International Electron Devices Meeting 1998. San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE. p. 1009. doi:10.1109/iedm.1998.746525. ISBN 0-7803-4774-9.

- ↑ P. A. Stolk, J. Schmitz, F. N. Cubaynes, A. C. M. C. van Brandenburg, J. G. M. van Berkum and W. G. van der Wijgert, "The effect of thin oxide layers on shallow junction formation," ESSDERC proceedings, page 428, 1999.

- ↑ Ho, Johnny C.; Ford, Alexandra C.; Chueh, Yu-Lun; Leu, Paul W.; Ergen, Onur; et al. (2009-08-17). "Nanoscale doping of InAs via sulfur monolayers". Applied Physics Letters. 95 (7). AIP Publishing: 072108. doi:10.1063/1.3205113. ISSN 0003-6951.

- ↑ Barnett, Joel; Hill, Richard; Loh, Wei-Yip; Hobbs, Chris; Majhi, Prashant; Jammy, Raj (2010). Advanced techniques for achieving ultra-shallow junctions in future CMOS devices. International Workshop Junction Technology. IEEE. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1109/iwjt.2010.5474968. ISBN 978-1-4244-5866-0.